UPDATED AUGUST 17, 2025

|

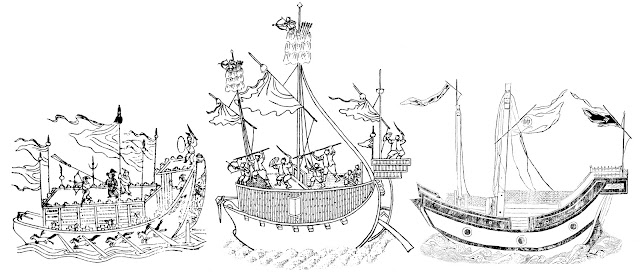

| Drawing of a Fu Chuan with full bamboo palisade, from 'Jing Guo Xiong Lue (《經國雄略》)'. Note its rolled, rather than folded, sails. |

The Fu Chuan (福船, lit. 'Fujian ship'), also known as Bai Cao (白艚, lit. 'White junk'), was a class of Chinese sailing junk originating in Fujian. It was the most widely used and well-known of the "Four Great Ancient Ships"

of China, and served as the mainstay of the Ming and Qing navies.

Fu Chuan as one of the "Four Great Ancient Ships of China"

|

| A replica Fu Chuan, claimed to be 1:1 in scale, recently launched in Quanzhou. Its V-shaped prow is visible in this photo. |

Fu Chuan was an oceangoing sailing ship that featured a S-shaped hull with both high

sheer forward and high sheer aft, with a deck that gradually widen towards the stern, a flat prow with no visible stempost that appeared as either a V-shape or ℧-shape when viewed from the front, and a flat, often richly decorated stern. It typically had one or more rectangular junk sails, as well as a slender retractable unbalanced rudder. Unique to the ship type, some large, oceangoing Fu Chuan were designed with the capability to quickly swap out their primary rudder with a smaller secondary one in order to traverse shallow water, and many were also fitted with mountings for additional Yuloh sculling oars that also served as auxiliary rudders (although auxiliary rudders seem to fell out of use by mid-to-late Qing period).

Fu Chuan during Ming period

|

| Replica Chinese junk "Fu Ning", built to commemorate Ming treasure voyages, probably resembles early Fu Chuan the most, although it lacks the stern overhang. |

Bambooclad warship

Fu Chuan was valued in warfare for its high availability, its large size giving it an advantage in naval ramming, and its tall profile, allowing for elevated firing platforms and advantageous boarding positions. Its most striking feature, however, was definitely the reinforced bamboo palisade called Zhu Pi (竹𦨭, lit. 'Bamboo bulwarks') lining its weather deck. Also known as Zhe Yang (遮洋, lit. 'Ocean cover') during Song and Yuan period, Zhu Pi was no flimsy fencing but sturdy palisade made of rows of tough bamboo poles and planking tightly nailed and lashed together with rattan cords, erected behind the ship's original bulwarks to provide additional shielding from strong waves and gunfire.

To better organise, categorise, and manage the growing Fu Chuan fleet during his anti-Wokou campaign, renowned Ming commander Qi Ji Guang (戚繼光) developed a standardised classification system, which divided Fu Chuan into five classes based on size (later expanded by others into six), described below:

Da Fu Chuan (大福船, lit. 'Great Fu Chuan')

|

| Drawing of a Da Fu Chuan, from 'Wu Bei Zhi (《武備志》)'. Note its prominent three-storey aftercastle, as well as reinforced superstructure built on top the hull. |

A Fu Chuan had two decks and a large superstructure built on its main deck. The lowest level of Fu Chuan was its hold, used to store stones, bricks and roof tiles serving as ballast. Above the hold was the berth deck where accommodation for ship's crew was located.

Above the berth deck was the main deck, which was almost entirely covered by an enclose superstructure that housed the galley (kitchen) and drinking water storage, and both sails and anchors were operated from here as well. The primary fighting platform of a Fu Chuan was the roof of its superstructure, which was heavily fortified by Zhu Pi or wooden battlement.

At Fu Chuan's stern, a three-storey tall aftercastle rose above the

superstructure. The bridge of Fu Chuan was most likely located here, as this arrangement

conferred many advantages such as placing the captain and the helmsman within

shouting distance of each other, allowing the captain to have a full view of the

entire ship thus making tight turns much easier, as well as sheltering the bridge from large

waves washing over entire ship deck during adverse weather.

Cao Pie Chuan (草撇船, lit. 'Grass cushion ship')

|

| Drawing of a Cao Pie Chuan, from 'Wu Bei Zhi (《武備志》)'. The aftercastle of Cao Pie Chuan appears to be reduced to just one storey. |

Hai Cang Chuan (海滄船, lit. 'Haicang Ship')

|

| Drawing of a Hai Cang Chuan, from 'Deng Tang Bi Jiu (《登壇必究》)'. Note the lack of bamboo palisade around its superstructure. |

Mark 4 Hai Cang Chuan, later renamed Dong Chuan (冬船, lit. 'Winter ship') or Dong Zai Chuan (冬仔船) was another downsized Fu Chuan likely originating in Haicang. It was nearly identical to Cao Pie Chuan but lacked Zhu Pi reinforcement.

Because of their similar size and role, Cao Pie Chuan and Hai Cang Chuan were sometimes treated interchangeably. By later period various upsized and up-armoured variants of Hai Cang Chuan also seem to supplanted Cao Pie Chuan entirely.

Kai Lang Chuan (開浪船)

|

| Drawing of a Kai Lang Chuan, from 'San Cai Tu Hui (《三才圖會》)'. |

Mark 5 Niao Chuan (lit. 'Bird ship') and Mark 6 Kuai Chuan (lit. 'Fast ship'), collectively known as Kai Lang Chuan,

were the smallest of the Fu Chuan warships. They were easily distinguishable from larger Fu Chuan by their pointed prows, hybrid sail-and-oar

propulsion (although oars were eventually phased out), and use of a single stern-mounted yuloh sculling oar. Niao Chuan and Kuai Chuan were too small to mount a protective superstructure like their larger cousins, making them relatively poor mainline combat vessels, although they excelled in harassing and scouting role due to superior speed and maneuverability. They

were also used to collect enemy heads from floating dead bodies after battle.

Transition to broadside warship

For much of China's history, the principal Chinese warship design was the

so-called "tower ship"—a warship whose primary fighting compartment consisted of a large and enclosed

superstructure built atop its hull. The design offered excellent

protection to ship's crew, fully leveraging on the superior projectile

weapon and shipboard artillery (namely

crossbow,

trebuchet, and

gunpowder bomb) used by the Chinese naval forces. Additionally, the ship's greater height also

made it less vulnerable to boarding.

Originally designed for riverine warfare during China’s Warring States period, tower ships were so successful that they remained in continuous use even after

more seaworthy hull designs emerged and sails replaced oars as the

primary means of propulsion. Ming period Fu Chuan was essentially the sixteenth century iteration of the classical tower ship and wouldn't look very

different from contemporary tower ship-equivalents, such as Japanese atakebune (安宅船)

and Korean panokseon (板屋船), save for the facts that it was smaller and more compact, lacked

the banks of oars of the other two ships, and had a proper aftercastle in place of a

mid-ship command tower. In fact, Fu Chuan was the direct inspiration

that led to the creation of the panokseon, and may have influenced the

development of Japanese warship as well.

Nevertheless, as Chinese shipbuilders began to mount more and

heavier guns

onto their warships, the primary weakness of the tower ship, namely, instability

caused by high centre of gravity, became increasingly intolerable. Echoing

similar developments in Europe, Chinese war junks also underwent significant revamps. Gone was the tall

superstructure, and the primary fighting compartment was moved to the main deck, with some developing a full-fledged gun deck inspired by European practices. While it is difficult

to pinpoint the exact date when the transition began (likely in the late 16th or early 17th century), the

process certainly took off with resounding speed. By the early Qing

period virtually all Chinese war junks had evolved into

the familiar quintessential form, and tower ships all

but disappeared.

Gan Zeng Chuan (趕繒船, lit. 'Chase-trawler ship')

|

| Drawing of a Gan Zeng Chuan, from 'Min Sheng Shui Shi Ge Biao Zhen Xie Ying Zhan Shao Chuan Zhi Tu Shuo (《閩省水師各標鎮協營戰哨船只圖說》)'. |

Originally a fishing ship, Gan Zeng Chuan was a key representative of a new generation of Fu Chuan that replaced older designs, coming into prominence in the final years of the Ming Dynasty and remaining in use well into Qing period. It was a two-masted Fu Chuan that carried heavier cannons like Fa Gong (發熕) on its single gun deck (which was also its weather deck), with several gun ports cut into its bulwarks.

.jpg) |

| Replica Chinese junk "Princess Taiping", which unfortunately sank after a collision with a chemical tanker, was based on a Gan Zeng Chuan. |

Although comparable in size to Mark 1 and Mark 2 Fu Chuan, Gan Zeng Chuan only served a role similar to a Cao Pie Chuan/Hai Cang Chuan, acting as a secondary mainline combat vessel, while the role of capital ship was held by the even larger Niao Chuan (鳥船).

Other blog posts in my Four Great Ancient Ships series:

Fu Chuan (福船)

So what about the replica fuchuan at the start, is it the late Ming era or Qing era fuchuan replica? Is there any other camera angle for that replica?

ReplyDeleteClaimed to be Ming, but I have my doubt.

DeleteThis is a news page with the same ship during its WIP stage.

https://new.qq.com/omn/20201221/20201221A0KD5I00.html

Where does the dimension came from? According to Wikipedia, Zheng He-era Fuchuan is about 50 m long

ReplyDeleteNo idea.

DeleteThere is no consensus about the size of Zheng He's ship. 50m seems small though as there were Fengzhou larger than that.

Will you discuss/post about Zheng He's fleet ships in the future? Such as baochuan, machuan, liangchuan, bingchuan, fuchuan (but those in the fleet), zuochuan and shuichuan?

DeleteNot in the plan right now, but eventually I will cover it as I learn more about them...I guess.

DeleteThere is an interesting paper by Andre Wegener Sleeswyk titled "The Liao and the Displacement of Ships in the Ming Navy" that attempts to re-evaluate the size of Cheng Ho's ships. There are references to Cheng Ho's fleet including ships of 2,000 liao and 1,500 liao on surviving stelae. Sleeswyk started with determining what a liao was based on Li Chao-hsiang's writings about the ships built at Lung-chiang ch'uan-ch'ang. His conclusion is that the liao is a measurement of volume/displacement (length x beam x height)^(2/3), with each of those measurements in ch'ih. Sleeswyk believes the author of Ming Shih excluded height for some reason and treated the liao as if it was just length x beam, multiplying the size of the ships significantly. Sleeswyk's conclusion is that the bao chuan was roughly 199 ch'ih (62 meters) in length, the ma chuan around 165.5 ch'ih (51.7 meters), and the fu chuan 80.5 ch'ih (25.2 meters), and that a liao is roughly half a modern ton of displacement.

Delete@Stephen

Delete62 m seems pretty in line with a 2,000 liao ship.

Sleeswyk's paper was written in 1996 I wager? The discovery of the grave of Hong Bao (a eunuch that participated in the voyage) in 2010 upped the size of Bao Chuan to 5,000 liao, so the current estimate is 75~84 m.

I apologize for not responding sooner, I hadn't come back to this page since posting my comment. Yes, Sleeswyk's paper was published in 1996.

DeleteLooking at the Wikipedia article on treasure ships with some trepidation, it looks like it's a much better article than it was just a couple years ago. There's mention of a 2011 paper from Zheng Ming that estimated the length of the 5,000 liao ship at 71.1 meters (https://www.doc88.com/p-2495318246868.html), with a roughly 5-to-1 length-to-beam ratio. That estimate, and the estimates up to 84 meters, are all plausible, although they'd have to have shallow drafts for their length if they were part of the Palembang expeditions because of limitations imposed by the depth of the Musi river. It's 6.5 meters now, but that's because of dredging, and historically it's been closer to 6 meters.

I am glad that more of these old records have been found and hope that more continue to be discovered. Luo Maodeng's novel helped keep the legend of the ships alive, and hopefully the realities we learn can be equally interesting.

How do the Fu Chuan described in this article compare to the ships from the Ji Xiao Xin Shu? From what I remember, there are two versions of that book, one with three ship classes and one with eight, neither of which would seem to perfectly line up with the six classes described in this article.

ReplyDeleteThis ship class list is taken from Chou Hai Tu Bian and was the most common one during Ming period.

DeleteQi Ji Guang's fleet went by Fuchuan (big) - Haicangchuan (medium) - Chongmuchuan (small), the smallest class was not a Fuchuan.

He also mentioned Cangshanchuan and Kailangchuan among other ships, but those were not counted towards proper warships of his fleet.

I found the source I was (slightly) misremembering. According to Elke Papelitzky's article "Weapons Used Aboard Ming Chinese Ships and Some Thoughts on the Armament of Zheng He's Fleet" (China and Asia 1, no. 2 (2019)), the three ship version of Qi Jiguang's ship description is from 1562, while the 1584 version has seven ship classes. The 1562 ships have fagong (the largest type only), folangji, and wankoutong as their larger-than-man-sized gunpowder weapons and range from 33-55 crew, while the 1584 ships have wudi shenfei pao, folangji, and baizichong and range from 11-88 crew.

DeleteI guess I was mostly curious whether the ships Qi Jiguang described existed or were "just" his theory on how ships should be put together, and how the ships were described if they were actually built (the only English-language references I've found to them are focused on the armament listed for them, rather than the ships themselves).

In second edition Jixiaoxinshu Qi Jiguang simply categorised all ships into No.1 to No.7 according to their sizes, irrespective of ship type. Essentially he introduced a form of standardisation of navy administration/command structure.

DeleteThank you very much for your work! I was directed here from a 2015 blog post about ship comparisons that mentioned observations on Fuchuan and I’m very interested in blogs related to naval history. Would you be interested in compiling information about the types of wood used in Ming dynasty ships at some point in the future?

ReplyDeleteI think it is hard to find info other than for Fuchuan and Guangchuan, but I will see what I can dig up.

Delete