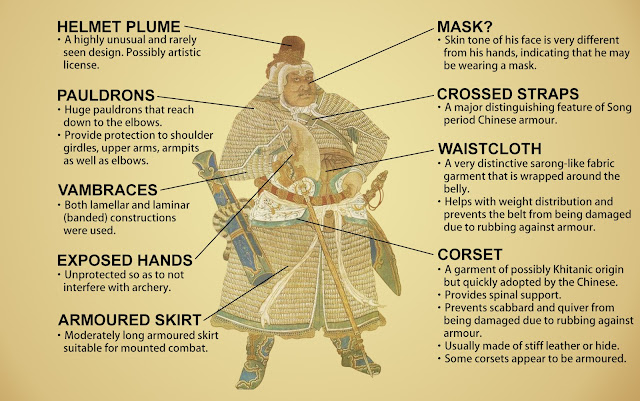

Traditional Chinese-style "Cataphract" Armour

|

| Components of Chinese-style "Cataphract" armour (click to enlarge). |

Armour in the above picture is taken from an unnamed wall painting at Baoning Temple located at Shanxi, China. The mural depicts an unidentified general or guard, quite possibly a Mongol (as the mural is dated to Yuan or early Ming period).

This type of heavy lamellar armour does not have a universally agreed name. It is dubbed "Cataphract" armour in this blog, but might be called Bu Ren Jia (步人甲, lit. 'Footman's armour') or Tie Fu Tu Jia (鐵浮屠甲, lit. 'Iron Pagoda armour') elsewhere, after its most famous users. The armour actually consists of three parts: A pair of large pauldrons, often but not always with characteristic crossed straps, a body armour that somewhat resembles a bib-and-brace, as well as an armoured skirt or a pair of tassets. Armoured skirt or tassets are sometimes integrated into body armour.

While Chinese warriors had been using various styles of similarly heavy lamellar armours since the Jin Dynasty, "Cataphract" armour only gained popularity during Song period. It was used by the Chinese, Khitans, Jurchens, Tanguts, and later adopted by the Mongols as well.

Analysis

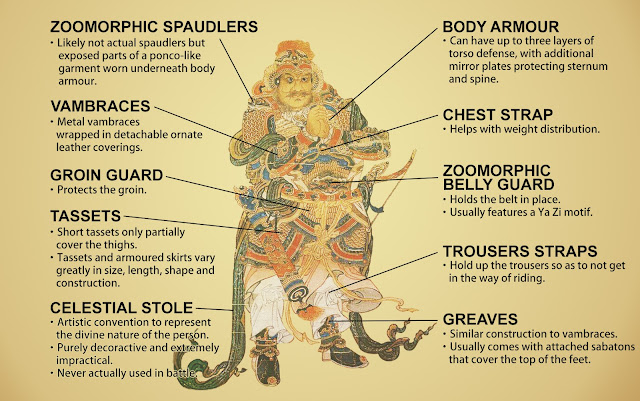

Armour in the above picture is taken from Di Fu Wu Dao Jiang Jun Deng Zhong (《地府五道將軍等眾》), a religious scroll painting depicting Wu Dao Jiang Jun (五道將軍), one of the Chinese deities of afterlife and guardian of the five entrances to hell. The scroll is also kept at Baoning Temple.

Zoomorphic armour components are perhaps the most striking feature of Chinese-style "Ornate" armour. "Spaudlers" and belly guard appear to be the most common, and can be found on most armours of this type, although some armours have additional zoomorphic decorations on bevor, throat, vambraces, tassets and greaves. These components are mostly decorative (most appear to be made from fabric or leather, rather than metal), although they still provide a little extra padding and protection.

As befitting an armour meant for the most elite, "Ornate" armour is also richly decorated with exquisite coverings, trims, fringes and embellished gems, all mounted on thick backings. While aesthetically pleasing, these decorations do little to improve the overall defensive qualities of the armour. Nevertheless, the trims and backings help tremendously to prevent wearing and abrasion, as well as muffle out most of the noise generated by the armour, making "Ornate" armour surprisingly silent for a heavy metal armour with so many interconnected parts.

As such, while "Ornate" armour is not more technologically advanced than its plainer counterpart (it is still only a suit of lamellar/scale armour after all), it is arguably* made to a much higher standard of craftsmanship and material quality, as well as custom tailored to its user, making the armour an overall superior choice to "Cataphract" armour despite its ornate appearance.

*NOTE: It should be reminded that quality difference isn't inherent to the armour design. It is entirely feasible to make a plain and undecorated "Cataphract" armour to the highest standard of craftsmanship, material quality and tailoring. In fact, I suspect that is what most field commanders would have preferred.

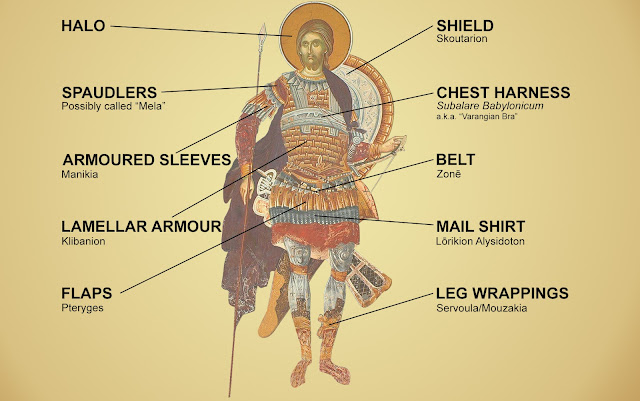

Byzantine Armour

Armour in the above picture is taken from the fresco of Saint Nicetas at Saint Nicetas monastery, located at Banjane, Republic of Macedonia. This fresco is roughly contemporaneous with the Chinese painting and mural above, although all three depict armour styles from much earlier period.

The fresco does not survive the ravage of time well and suffered numerous cracks and damages, so I took the liberty of doctoring the image in Photoshop in the hope that I can make it slightly more presentable. Unfortunately, while most damages of the fresco can be restored with some degree of accuracy, the bow holster portion of the fresco is damaged to a point where it is beyond my ability to repair. I am forced to redraw that portion based on nothing but imagination, so the bow holster in my doctored image is most likely completely inaccurate.

Analysis

The full panoply of a Byzantine kataphraktos consisted of an iron helmet (kassidas sideras) with double or triple-layered zabai (commonly believed to refer to mail curtain, although scale, lamellar, leather, felt, and padded fabric cannot be ruled out) covering the entire face, a lamellar cuirass (klibanion) with short armoured sleeves (manikia), which may be of splint, scale or "inverted lamellar" construction, padded lower sleeves or vambraces (manikellia) and padded skirt (kremasmata), both reinforced with zabai, greaves (chalkotouba or podopsella), as well as an overcoat (epilōrikion), which has a Chinese counterpart in the form of Zhan Pao (戰袍). Other kataphraktos wore helmet with mail or padded standard (perìtrachelion), coif (skaplion) and ankle-length armour (zabai or lōrikion), both of which may be of mail, scale or lamellar construction, as well as iron vambraces (cheiromanika sidera), omitting both manikia and kremasmata, and even klibanion depending on time period. Other armour components, such as mail, scale, and padded open-face aventail, lamellar kremasmata, protective strips skirt (pteryges), and the occasional scale or mail chausses were also known to be used by Byzantine warriors.

|

| Analysis of Chinese-style "Cataphract" armour (click to enlarge). |

Like many lamellar armours, "Cataphract" armour is designed for ease of fabrication, mass-production, modularity and versatility, yet still able to provide maximum protection to its wearer. Many components of the armour come in various standardised sizes depending on the user's height, weight, and combat role, and can be easily removed for comfort, replaced, or exchanged for another piece.

A full suit of "Cataphract" armour, as pictured above, completely covers its wearer from head to toe. It has remarkably few gaps and weak points for a lamellar armour, thanks to its large pauldrons that extend beyond the elbows and even partially cover the armpits, extra-long vambraces that also extend to cover the elbows, and long armoured skirt. Furthermore, some pauldron designs even feature integrated chest and back armours to add yet another layer of defence to upper torso, and the armour can be further reinforced with various auxiliary components such as bevor, mirror armour, underarm protector, groin guard and buttock guard to enhance its protective qualities.

A full suit of "Cataphract" armour, as pictured above, completely covers its wearer from head to toe. It has remarkably few gaps and weak points for a lamellar armour, thanks to its large pauldrons that extend beyond the elbows and even partially cover the armpits, extra-long vambraces that also extend to cover the elbows, and long armoured skirt. Furthermore, some pauldron designs even feature integrated chest and back armours to add yet another layer of defence to upper torso, and the armour can be further reinforced with various auxiliary components such as bevor, mirror armour, underarm protector, groin guard and buttock guard to enhance its protective qualities.

With its heavy construction and good coverage, this type of "Cataphract" armour is arguably the most protective body armour of its time (i.e. 10th to mid 13th century), surpassed only by later European coat of plates and full plate armour. In fact, widespread use of highly protective armours in China during Song period kickstarted the proliferation of heavy duty anti-armour weapons such as heavy crossbows, axes, various polearms, maces and two-handed morning stars on a scale never seen before, as both Chinese and their enemies became increasingly reliant of these fearsome weapons to overcome the heavy armour.

Unfortunately, the superb protection of "Cataphract" armour does come with drawbacks. As the armour is usually mass-produced and thus isn't specifically tailored to individual wearers, it inevitably affects the user's mobility. Additionally, its oversized pauldrons also hinder arm movement, while the crossed straps are at higher risk of being cut during battle.

Unfortunately, the superb protection of "Cataphract" armour does come with drawbacks. As the armour is usually mass-produced and thus isn't specifically tailored to individual wearers, it inevitably affects the user's mobility. Additionally, its oversized pauldrons also hinder arm movement, while the crossed straps are at higher risk of being cut during battle.

Traditional Chinese-style "Ornate" Armour

|

| Components of Chinese-style "Ornate" armour (click to enlarge). |

Like "Cataphract" armour, this type of armour does not have a universally agreed name. It is dubbed "Ornate" armour in this blog due to its ornamented appearance. This particular suit of armour is a composite type, consists of mountain pattern pauldrons, lamellar body armour, additional laminar chest armour, and scale tassets (although many Chinese "scale" armours are actually lamellar armours with scale-like lamellae). Despite looking nothing alike, "Ornate" armour is most likely just a heavily decorated "Cataphract" armour.

Analysis

|

| Analysis of Chinese-style "Ornate" armour (click to enlarge). |

As befitting an armour meant for the most elite, "Ornate" armour is also richly decorated with exquisite coverings, trims, fringes and embellished gems, all mounted on thick backings. While aesthetically pleasing, these decorations do little to improve the overall defensive qualities of the armour. Nevertheless, the trims and backings help tremendously to prevent wearing and abrasion, as well as muffle out most of the noise generated by the armour, making "Ornate" armour surprisingly silent for a heavy metal armour with so many interconnected parts.

As such, while "Ornate" armour is not more technologically advanced than its plainer counterpart (it is still only a suit of lamellar/scale armour after all), it is arguably* made to a much higher standard of craftsmanship and material quality, as well as custom tailored to its user, making the armour an overall superior choice to "Cataphract" armour despite its ornate appearance.

*NOTE: It should be reminded that quality difference isn't inherent to the armour design. It is entirely feasible to make a plain and undecorated "Cataphract" armour to the highest standard of craftsmanship, material quality and tailoring. In fact, I suspect that is what most field commanders would have preferred.

Byzantine Armour

|

| Components of Byzantine armour (click to enlarge). |

The fresco does not survive the ravage of time well and suffered numerous cracks and damages, so I took the liberty of doctoring the image in Photoshop in the hope that I can make it slightly more presentable. Unfortunately, while most damages of the fresco can be restored with some degree of accuracy, the bow holster portion of the fresco is damaged to a point where it is beyond my ability to repair. I am forced to redraw that portion based on nothing but imagination, so the bow holster in my doctored image is most likely completely inaccurate.

Analysis

|

| Analysis of Byzantine armour (click to enlarge). |

At first glance, Saint Nicetas appears to be severely under-equipped, lacking a helmet as well as any sort of limb protection. However it should be noted that equipment of military saints should not be taken as being representative of Byzantine military equipment as a whole, as period painters often intentionally omitted details such as helmet and overcoat in order for the saints to appear more identifiable and more "Roman-like".

The full panoply of a Byzantine kataphraktos consisted of an iron helmet (kassidas sideras) with double or triple-layered zabai (commonly believed to refer to mail curtain, although scale, lamellar, leather, felt, and padded fabric cannot be ruled out) covering the entire face, a lamellar cuirass (klibanion) with short armoured sleeves (manikia), which may be of splint, scale or "inverted lamellar" construction, padded lower sleeves or vambraces (manikellia) and padded skirt (kremasmata), both reinforced with zabai, greaves (chalkotouba or podopsella), as well as an overcoat (epilōrikion), which has a Chinese counterpart in the form of Zhan Pao (戰袍). Other kataphraktos wore helmet with mail or padded standard (perìtrachelion), coif (skaplion) and ankle-length armour (zabai or lōrikion), both of which may be of mail, scale or lamellar construction, as well as iron vambraces (cheiromanika sidera), omitting both manikia and kremasmata, and even klibanion depending on time period. Other armour components, such as mail, scale, and padded open-face aventail, lamellar kremasmata, protective strips skirt (pteryges), and the occasional scale or mail chausses were also known to be used by Byzantine warriors.

While undoubtedly very protective, Byzantine armour does have some major flaws, namely it does not adequately protect the joints (both elbows and knees) and thighs. Byzantine manikia are better fitted to the arms but also significantly smaller than the oversized Chinese pauldrons, often leaving the elbows exposed. Likewise, both pteryges and kremasmata are quite small (in fact they are slightly smaller than Chinese lamellar belly/groin guard meant to only protect lower abdomen) and only cover the upper portion of the thighs at best. Nevertheless, use of mail armour largely solved these issues.

Despite the shortcomings, Byzantine armour does have several advantages over Chinese armour, namely it does not restrict mobility as much as Chinese armour and, if mail armour is included, effectively has no gaps or weak points other than hands and eyes.

Despite the shortcomings, Byzantine armour does have several advantages over Chinese armour, namely it does not restrict mobility as much as Chinese armour and, if mail armour is included, effectively has no gaps or weak points other than hands and eyes.

|

| If you like this blog post, please support my work on Patreon! |

"That being said, not even a fully equipped kataphraktos of the tenth century can compare to a contemporary Chinese armoured warrior in term of protection."

ReplyDeletehttp://www.levantia.com.au/byzarmour.html

http://www.levantia.com.au/pdf/Dawson_KKK.pdf

https://www.pinterest.com/pin/315322411388284217/

The 10th century East Roman Kataphraktos on an armored horse was the equivalent of a tank, trained to break through infantry formations, with khoursores/medium cavalry intended to engage other horse. Dawson makes a case that pteryges in art are in fact the artist's way of depicting lamellar or splint armor, as they're shown as too rigid.

The chest harness was more than likely a rank indicator, since saints are usually depicted as officers, like centurions in art, a variation of the cloth sash, instead of a means of weight distribution, as even a common foot soldier would've had his armor easily altered in the field.

@Condottiero Magno

DeleteGood day and welcome to my blog.

I fully agree with you that Kataphraktos on armoured horse is the medieval equivalent of tank. However, I think my point still stands.

"Dawson makes a case that pteryges in art are in fact the artist's way of depicting lamellar or splint armor, as they're shown as too rigid."

I am fully aware of this and made a mention in the blog post.

Regarding the so-called "Varangian bra", AFAIK it is not mentioned in any of the Byzantine source (not even its actual name is known), so it's hard to be certain. However, similar items do serve the purpose of helping weight distribution on other armours (i.e. Chinese), so I think it's safe to say that Varangian bra does help, even if that's not its primary purpose.

I modified the Byzantine section of the article slightly so that my remarks appears less...volatile. It is not my intention to disparage armour designs of other cultures.

DeleteIn that chinese mural plates in armor looks so small

ReplyDeleteAccurate representation or just for a artistic expression?

Probably accurate. A Chinese lamellar can be made out of something like ~1800s of plates instead of several hundreds.

Delete"Additionally, the humble padded armour is another piece of equipment not available to the Chinese, at least until twelfth or thirteenth century, as cultivation of cotton did not become widespread in China until then."

ReplyDeleteI know that cotton armors appeared rather late in Chinese history, but they had paper and leather armors before, aren't those somewhat similar to padded armor?

Yes, but they didn't wear it on top of lamellar armour like the Byzantines, as far as I am aware.

DeleteHi!

ReplyDeleteI really like this series of yours, is really educational and explanatory.

Regarding the "Cataphract" armor, I have some question;

Which kind of lamellar structure was used? (size and thicknesses of the lamellae and laces patterns)

And also, how much does this configuration weigh? It looks fairly heavy!

And finally, some food for thought.

Unlike Europe, in the Far east, like Japan or China, apparently, mail armor was rarely worn as a form of primary/standalone protection, lamellar was the mainstream form of armor since ancients periods. Do you think that this has something to do with the amount of projectiles and ranged weapons used? (horse archery and crossbows).

I think that, compared to the West, Asian warfare saw more volume of arrows/darts and projectiles than the average European medieval, especially when we consider Horse archery, something rarely seen in the West. But I wanted to hear your opinion!

Warriors of stepp often use mail as much as maile

DeleteBeside usage of maile in far east is still debatable

@Gunsen History

DeleteThanks for your support!

Here's a Jin Dynasty lamellae plate for your reference (although this is not the only type). The lamellae plate has a slighty curved surface to increase strength. Average thickness is around 1.2~1.5mm thick, although 2mm thick lamellae is not unheard of. I think I've seen the instruction to lace/assemble them somewhere, but I am unable to find it at the moment.

https://i.imgur.com/b1ggMjB.jpg

Yes, the armour was indeed known to be extremely heavy, around 30kg for the heavier infantry variant.

cont'd

DeleteWhile I do think that Asiatic warriors having more and better projectile weapons does factor, socio-econimic & cultural factors probably played a bigger part.

Broadly speaking, lamellar armour has several characteristics:

1) Low material requirement - It can be made out of almost anything, thus very suitable for material-poor cultures (i.e. steppe nomads etc).

2) Can be manufactured quickly if needed be, thus making it idea for large empire like China that'd rather outfit tens of thousands of troops with okay armours instead of giving a few elite units the absolute best. On the flip side, lamellar armour can be a nightmare to maintain/repair/clean, so the long term cost is higher.

3) While actually replacing broken lamellae and torn lacing are difficult, field repair is very easy, as you can simply swap the broken parts for a new replacement.

Thank you for the references!

DeleteI didn't think about all of these factors but now is even more clear why they didn't adopted on a wide scale mail armor, especially in the Chinese context

Hello, this is Joshua again

ReplyDeleteI always heard many comment that the Song Dynasty period have the heaviest armor in Chinese and it is also the time where their enemy wore the heavier armor than before, yet when I search more and more into the Tang Dynasty period, I found that the Tang also have a lot of heavy armor and almost all of their enemy are also heavily armored, like I mean full body armor like European knights. Could you check about it? What make the Song Dynasty period special in armor?

If you want pic sources, I could give it to you.

Also I found out that in the Tang Dynasty and 5 Dynasties 10 Kingdom, Chinese armors have a tubular sleeve that fully protect like mail, not only that, it seems that a lot of laminar and plate armor are also used. They even have a strange mail weave pattern I never see anywhere else.

However I found out that all of it is almost gone by the Song era, could you find a reason for it? Why do the Chinese abandon rigid plate armor and laminar and stick with flexible lamellar and mountain pattern, while European use less and less mail and change to plate and other transitional armor?

Also I think what you said about cataphract armor in the comment is right, it might be volatile, but in my opinion by the Tang period, armor technology around the world already surpass what the Roman and Sassanid have and would not be equalled until European full plate armor.

Could you make an article about Chinese armor in the Yuan Period?

Good day Joshua.

DeleteIndeed, Tang had armours just as protective as Song "Cataphract" armour (if not more so, since at least some of them wore mail under regular lamellar), and their enemies (Tibetans for example) were also heavily armoured. The hearsay of "Song Dynasty heaviest armour" probably stem from the fact that we have some records on the weight of Song armour, but don't have any on Tang armour (as far as I know).

As far as I am aware, tubular sleeve were only in use from Han-Jin period, and fall out of use after that. Some Tang armours have large, flexible zoomorphic "sleeves" but no pauldrons. I don't think the "plate and cord" armour or so-called "Mingguang armour" disappeared after Tang. You can still find elements of Tang armour on some of the Ming period "Ornate" armour.

There was actually a period of overlap where BOTH Chinese and Europeans (and elsewhere) switched to cloth-covered metal armour such as coat of plates and brigandine. Even after the emergence of full plate, lower-ranked troops continued to wear brigandines.

I think the reason Chinese stuck to lamellar and later brigandine was mostly economical - they're cheap and certainly "good enough". This happened whenever a state wanted to raise a relatively massive army, but still wanted the army to be reasonably trained, professional and well equipped.

While some armours are objectively better than other armours, and I am hardly innocent for writing these comparison articles (I can't be complete without bias after all, and I actually had to edit my previous armour comparison article numerous times as well), the intension of including armours of other cultures is to compare and contrast the design considerations of these armours, not to rile up the feeling of "my armour is better than yours!". These armours obviously worked well on their respective battlefields/time period.

As far as I am aware, Yuan simply inherited the Song/Jin/Liao armour designs whole and then passed them down to the Ming, with hardly any modifications (in fact, the guy wearing that "Cataphract" armour is likely a Mongol).

"Yuan simply inherited the Song/Jin/Liao armour designs whole and then passed them down to the Ming, with hardly any modifications"

DeleteDidn't the Yuan also introduced brigandine armor to China and Korea? There was a Japanese painting about the Mongol invasion of Japan and it seems that most of the Mongol soldiers on that scroll were wearing brigandine armors.

@The Xanian

DeleteMongol (not necessary Yuan Mongol) introdution of brigandine is a possibility and most likely true, although far from a concrete theory, especially on how or when it happened. To my knowledge Ming and Joseon only started using brigandine during fifteenth century, several decades after Yuan period.

Most Mongol soldiers on the Japan invasion scroll appear to be wearing 1) no armour 2) padded armour (no studs) or 3) lamellar. There are several soldiers wearing something that might be brigandines (with red coloured dots), but one of them actually his armoured skirt flipped slightly - and reveals no plates underneath. I personally think that those red dots represent stitches and they are wearing padded armours as well.

Tang Tubular Zoomorphic pauldron

Deletehttps://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/70/Dinastia_tang%2C_guerriero_lokapala%2C_618-906_dc_02.JPG/477px-Dinastia_tang%2C_guerriero_lokapala%2C_618-906_dc_02.JPG

Tang laminar arm armor

http://www.zgmdysw.com/KUpload/image/20150529/20150529141415_9165.jpg

Tang lamellar tubular upper arm armor

http://5b0988e595225.cdn.sohucs.com/images/20171012/858b48c7a2484acdbe4970ccb5c02048.jpeg

That is what everyone said the Yuan dynasty doesn't introduce new armor.

How many Yuan dynasty period scroll and painting showing soldiers are there? I have search for a long time, but only a very small amount and that are religious pictures meaning it is meant to be unrealistic.

I mean even the painting of the mongol invasion of Japan already show different armor than the Song.

Also where do you find the term for both Byzantine and Chinese armor components?

Also the comment about plate armor, I don't know about that. Didn't the European produce a very large amount of plate armor for normal soldiers in the 30 Years War and even before that?

DeleteThe Chinese have certainly make large amount of metal plates before, I heard about metal plated ships in the Song-Jin war, so why not plate for soldiers.

I think it may have been the way the Imperial Chinese military operate. The theater is very large compare to Western European theater where cities are close to each other, while the Chinese operate in an area more like Russia, although there are crowded areas, they would also operate in widely different climates such as tropical jungles and steppes, not only that, but China also have few amount of coastline meaning they have to travel long distances through canals or land.

Lamellar and brigandine are easier to store. They can be folded to save space just like Japanese tatami armor. Meaning more armor can be sent or stored for more soldiers.

Probably ease of repair for normal soldiers is also another reason. It is probably easier to replace lacing and lamellar plates than hammering back damaged plate armor without forges in the field.

I mean try wearing a cuirass that have a hole from a musket ball or which have been ripped by cannonball, even when hammered the edge would still be sharp, whereas with lamellar you can just cut the lacing and tie new plates.

Also what I find interesting is why the Japanese and Korean abandoned plate armor early on. The Japanese did return to plate armor, but the Korean generally did not.

Maybe plate armor interfere with archery?

Also what is your opinion about this armor?

http://img2.itiexue.net/2067/20675378.jpg

I have read about it being mentioned as Xiong nu armor and sometimes Yuan dynasty armor. It could also be modern creation and then buried to make it look old.

@Joshua

DeleteThe picture with Tang tubular lamellar sleeves is new to me. I've seen that before, but did not pay attention to the sleeves. Come to think of it, those sleeves are remarkably similar to what the Byzantine used.

Actually Mongol armours in the Japan invasion scroll are hardly any different from Song armour (most of them are without pauldrons though).

There aren't many paintings from the Yuan period (since it isn't my focus), and what I have come across depict soldiers in "Cataphract" armours anyway.

Byzantine terms for armour components really aren't that difficult to find, most of them can be found by Googling. For Chinese ones, I afraid you have to dig through numerous historical texts.

On European plate, it was definitely a technologically advancement. However, there was also a general drop in the quality of soldier's kit during the same period - armies became larger, but troops became less armoured in general (which paralleled the situation in China, more or less). Top quality full plate with heat-treated steel became increasingly rare, even though they offered superior protection against firearms compared to wrought iron three-quarter armours used by 17th century cuirassiers, plus lighter to boot.

DeleteWhile you can repair lamellar armour with less skill/craftsmanship, it gets damaged easily and pretty much requires constant maintenance, so I wouldn't say it is easier to repair than plate. Chinese switched to brigandine partly because they got pretty fed up with the (maintenance of) lamellar .

Thank you for the information.

DeleteIf the Chinese switch to brigandine because of maintenance, why do they do it so late in history? Rivet should be available even earlier times than the Ming Dynasty.

http://img2.itiexue.net/2067/20675378.jpg

Also have you seen this thing?

@Joshua Immanuel Gani

DeleteAFAIK, early plate armours like the Japanese/Korean armours are pretty terrible in quality and a far cry from European breastplate, but I don't know much about them.

The idea of riveting metal plates to the back of a coat probably didn't occur to them before 15th century... or so I thought.

I know about that Mongol/Xiongnu "plate" armour. Personally I think that's more likely to be Mongol (since large Mongol laminar plates had been excavated elsewhere), but I can't be too certain.

Isn't brigandine just scale armor except the scale is on the inside? How difficult it is to do it?

Delete@Joshua

DeleteMore or less. Brigandine is supposedly easier to make than scale/lamellar. Why it didn't appear earlier (for everyone, not just Chinese) is anyone's guess.

True.

DeleteBrigandine suddenly became widespread in the 14th century to 15th century and armies from Europe and Byzantine Empire to Mongol, Persian and Chinese start using it. Later on, there are also Rajput brigandine.

Awesome discussion you guys had, I wanted to ask are they any good books funny evolution of Chinese armor or perhaps Central Asia armor in English also as to whether the Mongols use brigandine in the invasion of Japan yours is Museum in Japan that show some examples of armor used during The Invasion it's brigandine

Deletehttps ://www.google.com/search?q=armor+used+during+the+mongol+invasion+of+japan&client=ms-android-boost-us&prmd=insv&source=lnms&tbm=isch&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjc14et2LTYAhWDzIMKHUBNC6UQ_AUIESgB&biw=320&bih=489#imgdii=qz0zUk7_9NYjRM:&imgrc=8GEXTORnuve4vM:

https ://www.google.com/search?q=armor+used+during+the+mongol+invasion+of+japan&client=ms-android-boost-us&prmd=insv&source=lnms&tbm=isch&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiK2cyX2LTYAhWhx4MKHdfFBv0Q_AUIESgB&biw=320&bih=489#imgdii=rY-TKa1jDZafUM:&imgrc=T5rtuP9A_4ij6M:

https://www.google.com/search?q=armor+used+during+the+mongol+invasion+of+japan&client=ms-android-boost-us&prmd=insv&source=lnms&tbm=isch&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjc14et2LTYAhWDzIMKHUBNC6UQ_AUIESgB&biw=320&bih=489#imgrc=8GEXTORnuve4vM:

httpsww.google.com/search?q=armor+used+during+the+mongol+invasion+of+japan&client=ms-android-boost-us&prmd=insv&source=lnms&tbm=isch&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjc14et2LTYAhWDzIMKHUBNC6UQ_AUIESgB&biw=320&bih=489#imgdii=PpvAOfhHH3cYkM:&imgrc=8GEXTORnuve4vM:

I'm sorry if none of the links I left work type in Mongol armor in Japanese Museum or something, you should see some images

DeleteWhere it says funny in my first comment it supposed to say good sorry I don't know what went wrong

DeleteGood day Kevin.

DeleteThe thing with Japan's Mongol Invasion Museum is that it often mistakenly label various weapons and armours coming from China and Korea as Yuan armour. So I treat anything coming from them with huge suspect.

If you two don't mind, there is a rather simple argument for Song armor being the heaviest on average.

DeleteSimply because known values are already next to borderline for rank-and-file men. Both infantry and cavalry(accointing for barding).

Heavier suites are certainly known, but they don't fit the criteria.

Indeed the heaviest Song Dynasty armour was more or less the upper ceiling of how heavy a footsoldier could wear.

DeleteHemp was used in ancient China and the plant fiber is pretty tough. Depending on the specific species of hemp it could be tougher than linen. It could even be made into armor like linen armor reconstructions. It's likely that the thick hemp robes (worn underneath armor or by itself) of the Qin/Han terracotta army offer some protection against slashes and cuts, but not much against stabbing attacks.

ReplyDelete@The Artificer

DeleteGood day and welcome to my blog.

Padding for Chinese troops will make an interesting topic on its own, I will try to look into that.

It is true that sufficiently thick clothing can be used in place of padding, plus China also produced silk and paper. Ming troops defenitely wore cotton padding underneath their armours, and sometimes over. Song troops MOST PROBABLY also used some form of padding made of other materials.

Every Chinese armor I see almost always have some kind of backing that looks like leather, maybe that provide the padding.

DeleteDo the robe the Chinese soldiers sometimes wear over armor act the same as surcoat didß

Pretty sure they had to have had some sort of padding or else the armour might chafe too much.

Delete@wakawakwaka

DeleteThat reminds me, I guess I have to write a topic about this.

Hello, could I ask you something connected to byzantine armour. I am looking for an answer : what is the white belt worn by many saints in iconography, f.ex. saint George. I send you pic here: https://iconreader.files.wordpress.com/2012/04/georgeandthedragon.jpeg

ReplyDeleteGood day and welcome to my blog. I am far from an expert in Byzantine stuff (actually I barely know anything about them), but I think the sash is called "zone stratiotike" and seem to be the artists's attempt to emulate the military band worn by Classical Roman officer. Most I've seen are worn horizontally rather than diagonally though, and not all are white in colour.

DeleteI wonder where could you find so many resources of old paintings describe the military units?

ReplyDeleteBy digging down the internet basically. It's not easy, we don't have something like Manuscript Miniatures/Effigies & Brasses Database for Chinese stuffs, but these stuffs do accumulate over time if you are persistent.

DeleteTrue,I seldom found high quality resources, even many papers used these paintings.

DeleteNeither do I.

DeleteHello,

ReplyDeletei have been slightly going mad while thinking about chinese armpit defenses exspecially of lamellar like in the picture with the khitan general. Would have some cases of armpit defenses? And what the source is for the iron pagoda song army and khitan general pictures.

Thank you

Love your blog

Sorry, I'm afraid I don't quite understand your first question.

DeleteAs for the second one, the "Iron Pagoda" come from 《中兴瑞应图》, while the Khitan general come from a Qing Dynasty copy of 《文姬歸漢圖》, originally from Southern Song period.

What i mean are there any sources of armpit defences beside the one example you give in the picture with the khitan general?

ReplyDeleteqing ming joseon brigandine have their own armpit armor and it just looks like khitan general's

DeleteYes.

ReplyDeleteThey are fairlay well known but anything like for lamellar maybe a better depiction like the kitan general its kind of just a few lines.

ReplyDeletehttps://i.imgur.com/ESHNogB.png

DeleteI believe there are some surviving pieces from outer Mongolia or Russia, can't find them at the moment though.

DeleteAmazing picture! Is it song ore ming dynasty? Are you familiar with the works of Michael Gorelik on MOngol armor? I think i say a drawing of them there.

ReplyDeleteThe painting was falsely attributed to Tang period painter Wu Daozi (吳道子) but actually from Song period. I am aware of Gorelik's research, unfortunately I can't read Russian so I am not familiar his works.

DeleteThe painting is currently owned by The Cleveland Museum of Art, Ohio, US.

I know some russians if there is any specific chapter you are interested in maybe i can do something .......

ReplyDeletehttps://www.pinterest.co.kr/pin/368380444523231223/

ReplyDeleteI have found very curious image

it seems to be some sort of lamellar armor with possibly heart mirror armor

i never seen any Chinese weapon encyclopedia that blatantly drawing heart mirror armor

uploader claims this to be a ming period treatise

Yes, I believe it is legit, I am still trying to track down the source though.

DeleteI don't think we can say "Cataphract armour only gained popularity during Song period" because depending on how we define cataphract armor, it gained popularity long before the Song.

ReplyDeleteIf we define cataphract as having the horse either being "at least partially" armored in metal armor or fully armored in any type of armor (metal or organic), then the cataphracts would date to at least the Han Dynasty or even the Warring States era. During the Western Han Dynasty, there are armory records discussing thousands of sets of horse armor so it was relatively popular even during the Han era - though I believe we aren't sure if this was partial or full horse armor. There are archaeological discoveries of lamellar horse armor and it's believe that horses were covered in full suits of rawhide lamellar armor during the Warring States to Qin era.

If we define "cataphract" as having the rider and horse "fully armored" in "metal" armor, than cataphracts have been around since the Three Kingdoms or Jin Dynasty period in the 3rd or 4th century AD. There are lots of records, archeological discoveries, and paintings/artistic depictions of horses with armor during this time. So the latest time when we can say cataphracts became popular is the Jin Dynasty of the 4th century AD.

In terms of what exactly qualifies as a cataphract, I've seen a few books about Mediterranean and Middle Eastern cataphracts that portray partially armored cavalrymen with horses having partial metal, cloth, and/or rawhide protection as "cataphracts."

I've make it pretty clear that "cataphract" armour mentioned here is simply a dub to refer to a specific style of armour, "Bu Ren Jia" is a bit of a mouthful.

DeleteChinese cataphract (the heavy armoured cavalry) became really popular during Northern & Southern Dynasties period, but this type of armour became prominent during Song period.

I would be wary of ever using saint art as indicative of anything as byzantine armor goes. We know form the actual text that there was likely no gap, and the tassets should be very long, not the short skirts seen in saint art. More importantly saint art barely changes across literal centuries, and the Greco-Romans had a culture a bit averse to actually depicting their military in any accurate manner. Generally speaking it is very, very unreliable to use any Eastern Roman artwork as descriptive of contemporary armor, as it is more in the realm of complete fantasy. Even Dawson's reconstruction of Klivanion is suspect as it relies entirely on saint art instead of empirical finds (with all known lamellae finds just being pieces lacking their organic connection). For all we know Klivanion was actually a lamellar cuirass sewn to itself with no backing, it was affixed to a single backing, or it had multiple "bands" as Dawson asserts. Furthermore you are completely forgetting the Epilorikon, which was a thickly padded silk or cotton gambeson covering the entire torso, likely down to the shins, with the arms put out through the sleeves with the sleeves affixed to the shoulder as some kind of rear-facing textile pauldron.

ReplyDeleteActually, I did adress your concern in the article ("equipment of military saints should not be taken as being representative of Byzantine military equipment as a whole"), and I explicitly mentioned epilorikion.

DeleteI also avoided mentioning the lamellar construction of byzantine armour because frankly, I also have doubts on Dawson's reconstruction of Klivanion. However, gaps are bound to exist in most forms of lamellar armour.

Lastly, to the extent of my knowledge, "tassets" or Kremasmata are often described as some kind of padded skirt, and most of them seem to reach somewhere above the knees, even in artworks that do not depict military saint (such as Madrid Skylitzes), so my point still stands.

None of the artwork is a valid source because it's completely entrenched in "al antica" style that is unchanging for literal centuries due to the culture of the Orthodox Church, and the relative non-militant nature of common culture for a general lack of interest in military affairs (as there weren't even things like fencing treatises). What we do know from textual evidence however directing the soldiers to be armed was that the heavy cavalry was supposed to quite literally be protected head to toe, the only parts of the body exposed being the hands and eyes. The artwork doesn't even depict the armor of the Kataphraktos, ever, as no surviving images even exist of ERE heavy cavalry.

DeleteIt should be noted that I list out the full panoply of a Byzantine kataphraktos in my article, and made my analysis of Byzantine armour based on everything I listed (including the epilorikion), rather than the artwork of the military saint. Regardless, my opinion on Byzantine armour stays the same.

DeleteBy themselves, "Protected head to toe" and "this and that body parts exposed" don't really mean anything in an armour comparison context, because most heavy armours protect its wearer from head to toe anyway. For example, a samurai wearing a full suit of Tosei Gusoku is quite literally "protected head to toe", and only has his eyes exposed, yet we know for a fact that gaps exist on samurai armour. Byzantine, Chinese, or most forms of armours for that matter, are no different.

To Wyatt:

ReplyDeleteWhile rare, depiction of Byzantine full body armor do exist, however, there is no depiction of the 10th century Cataphract that I know of.

From the description in the Byzantine military manual, Byzantine Cataphract armor cover the whole body, but with the exception of helmet with mail veil, it is pretty much the same as what is worn by Tang soldier. It is heavy for 10th century Europe and Middle East, but not exceptionally sophisticated or heavy in Central or East Asian context.

To 春秋戰國:

I agree with your assessment, but I think it is better to link a picture from this site to show what a 10th century Byzantine cataphract look like.

http://www.levantia.com.au/katafrakt.html

The Byzantine lack in comparison to the Song and Ming Chinese armor:

- Independent rigid thigh armor

- Vambrace

- Rigid foot armor

- Solid plate or laminar chest armor (if we disregard muscle cuirass depiction)

The Byzantine have the advantage of mail armor, which make it easier to protect gaps. Mail is of course not necessary to cover gaps, just make it easier.

Also the comparison would be even more lopsided in favor of the Chinese, if we compare it to previous Tang, Five Dynasties Ten Kingdom and early 11th century Song armor.

Good day Joshua.

DeleteWhile I agree that Dawson's reconstruction at Levantia is very good, I do have other considerations to not include his photos in the blog post (mostly because I am too lazy to contact him and ask for permission).

Some comments on their reconstruction:

1) Byzantine "Zaba/Zabai", literal meaning "screen", is often interpreted as mail armour. The reconstruction seems to follow that interpretation.

2) The reenactor simply wears a long mail shirt under his lamellar armour to represent both manikelia (lower arm protection) and kremasmata (thigh protection). They are actually supposed to be separate pieces of equipment made of padded silk or cotton + zabai.

3) Although not present in Dawson's reconstruction (he attempted to closely follow Byzantine cataphract equipment as outlined in Praecepta Militaria), Byzantine soldiers did make use of metal vambrace.

I do take metal vambraces into consideration for my comparison.

4) Dawson's reconstruction of Byzantine greaves is pretty much guesswork. He probably referenced contemporary Khazar-style greaves though.

5) I am actually very skeptical of his reconstruction of gigantic, tube-shaped, knee-covering splint greaves. Neither Valsgärde 8 splinted greaves nor Borisov tubular greave cover the knees, soI have no reason to assume Byzantine greaves do (until proven otherwise).

(hence my "does not adequately protect the thighs and knees" comment in my analysis)

Thank you for you reply.

ReplyDeleteI am aware that the mail forearm and skirt of Byzantine cataphract armor is a separate component. That is why I said that Tang Dynasty soldier had similar equipment in the form or rigid vambrace and lamellar skirt.

There are actual painting of Byzantine greave in forms that either cover the knee or not, but they are mostly from after the 10th century. However, I have never seen any painting of Byzantine vambrace, the closest I get is Georgian 14th century Mongol influenced vambrace.

In comparison with Byzantine armor, wouldn't the only gap remaining in Chinese located in the underside of the upper arm and the armpit is protected by a Wakibiki style armor?

One variation of Song leg armor already enclose the most exposed area on the leg leaving only the behind open.

https://assets.catawiki.nl/assets/2019/5/22/b/0/b/b0b38fd2-330a-4481-a369-42ab42eb0e47.jpg

I am not aware of the existence of any Byzantine greaves, be it before or after 10th century. Madrid Skylitzes and Byzantine's Alexander Romance contain a few depictions of scale, mail or lamellar chausses, but that's basically it.

DeleteIf you have artworks of Byzantine greaves, please share them with me.

Greave that cover the knee - 14th century

ReplyDeletehttps://img-fotki.yandex.ru/get/4/32728872.5/0_7180b_c41289_orig

Greave that just cover the shin - 15th century

http://cp14.nevsepic.com.ua/217/21647/1389997754-dsc05238.jpg

Georgian vambrace - 14th century

https://i.imgur.com/4mdsWOY.jpg

@Joshua

DeleteDifficult to tell if the first picture really depicts greaves, they seem to extend all the way to cover the entire leg, which will make the legs impossible to bend.

I've seen the second one. Yes, those appear to be greaves under leg wraps.

Georgean vambraces appear to be similar to bazuband. Interesting.

I remember there is probably more picture of Byzantine greave, but I don't pay attention to them.

ReplyDeleteThere is also a picture with Poleyn and Sabaton, but it is Serbian. There is also a Byzantine painting showing what looks like a gauntlet.

If you notice, the Georgian painting also show greave with knee guard.

You could find a greave and vambraces with similar form in contemporary Mongol painting as well, it is probably adopted from the Ilkhanate.

Late Byzantine period saw widespread adoption of Western European equipment to the point that Byzantine troops effectively became indistinguishable from Western-style plate armoured knight.

DeleteFor the purpose of this blog post, I think it's better to leave knightly armour components out. In any case, this blog post will need some reworking in light of new info. Thanks for sharing with me.

Could you give me the Chinese name for sourcers which conntain depictions of the iron pagoda ?

ReplyDeleteOre where i can find them.

Friedn of mine is making himself an armour set.

If you mean graphical depiction, the main source is a painted scroll called 《中興瑞應圖》 (A cropped out part of that painting can be found in this very article).

DeleteWritten sources are more fragmentary. History of Song (《宋史》),《順昌戰勝破賊錄》 ,《大金國志》 among others have a few mentions about Iron Pagoda.

so how does coat of plates compare in protection to Lamellar anyways?

ReplyDeletePersonally, I believe Coat of Plates and brigandine are better than lamellar - but no one has done any comparative testing as of yet so I can't say it is definitely the case.

DeleteThey are much easier to maintain than lamellar at least.

I think they probably perform about the same, coat of plates reminds me a bit of the old roman armours but wrapped in cloth

Delete