Repeating crossbow is one of the unique inventions of China. Although the invention is commonly attributed to

Zhu Ge Liang (诸葛亮), the basic design actually predates him by several centuries.

Liang Shi Bing She Lian Fa Nu (兩矢并射連發弩, lit. 'Double-shot rapid fire crossbow')

|

| Earliest surviving example of a repeating crossbow, excavated from a Chu tomb. Currently kept at Jingzhou Museum. |

Excavated from Tomb 47 of the

Qin Jia Zui (秦家咀) tomb complex, this is the earliest archaeological evidence of a repeating crossbow, dated to 4th century BC. Note that this crossbow predates all written records of repeating crossbow, so it does not have any official or historical name. It is commonly referred to as

Zhan Guo Lian Fa Nu (戰國連發弩, lit. 'Warring States period rapid fire crossbow') or

Chu Guo Lian Fa Nu (楚國連發弩, lit. 'Rapid fire crossbow from the State of Chu').

|

| Internal workings of the Lian Fa Nu. Early restoration attempts created a model that does not have crossbow prod, but this was fixed in later models. Image taken from 《戰略‧戰術‧兵器事典》 vol. 1. |

|

| Replica Lian Fa Nu alongside the original fragment, Military Museum of the Chinese People's Revolution (exhibition). |

Lian Fa Nu is actually more advanced than repeating crossbows of later period. Its box magazine, large enough to hold twenty bolts (for ten shots, as it shoots two bolts at once), is fixed on the stock and therefore more stable. Its vertical foregrip and spanning device also allow the user to shoot the crossbow with a slingshot stance, making it easier to aim. Nevertheless, Lian Fa Nu does have several drawbacks, as it requires a complex metal trigger mechanism (making it too expensive for civilian home defence), is prone to jamming, and is weak even by repeating crossbow standard.

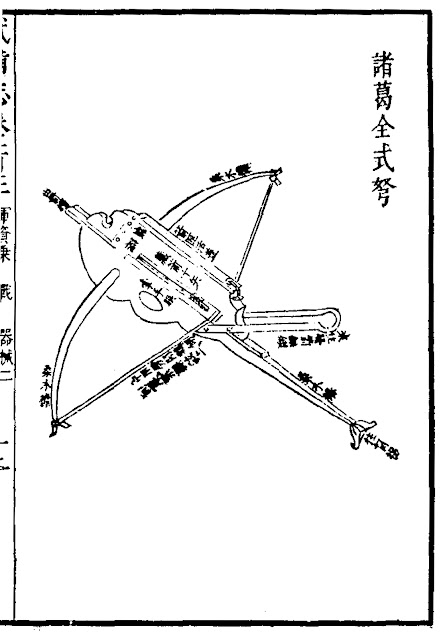

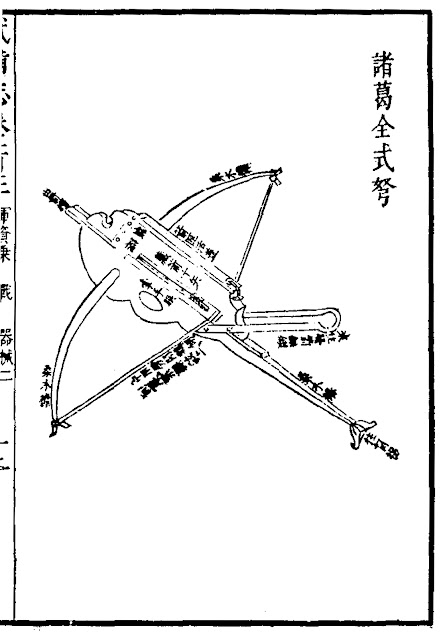

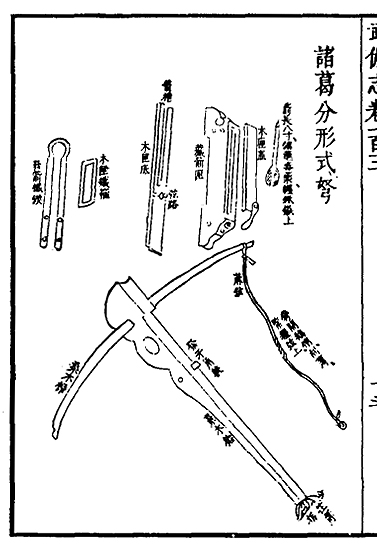

Ming Dynasty Zhu Ge Nu (诸葛弩, lit. 'Crossbow of Zhu Ge Liang') or Lian Fa Nu (連發弩, lit. 'Rapid fire crossbow')

|

| Drawing of a Zhu Ge Nu, from 'Wu Bei Zhi (《武備志》)'. |

Sometimes romanised as Chu-Ko-Nu, this well-known repeating crossbow only dates back to Ming Dynasty. It is a rugged design that is cheaper (as it does not require any metal parts) and more reliable than ancient Lian Fa Nu, and serves as the base model for later derivations.

Zhu Ge Nu has a magazine that holds ten arrows, and is spanned by a lever. The lever works on a similar principle to that of a European latchet crossbow, in theory allowing a very powerful prod to be used. However Ming Dynasty Zhu Ge Nu only mounts a small prod made of Chinese mulberry or lashed bamboo strips. Unlike later models, Ming Dynasty Zhu Ge Nu shoots fletched arrows.

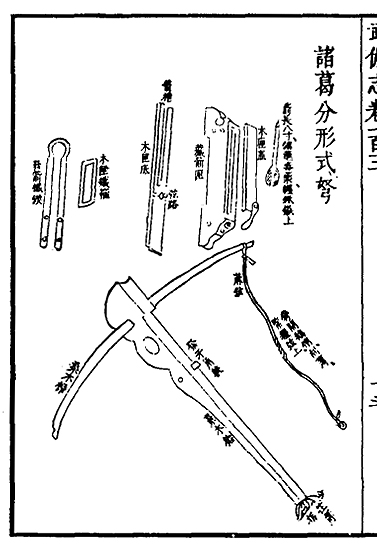

|

| Components of Zhu Ge Nu, from 'Wu Bei Zhi (《武備志》)'. |

The design of Zhu Ge Nu reflects a mindset that favours rugged reliability over pure performance (which may be the reason why powerful but delicate composite recurve prod was not used), a mindset shared by many militaries in the world. Nevertheless, Zhu Ge Nu was still considered ineffective as battlefield weapon.

Qing Dynasty Repeating Crossbow

|

| Training manual for repeating crossbow, from 'Bing Ji Zhi Zhang Tu Shuo (《兵技指掌圖說》)'. |

Save for some minor differences, Qing Dynasty repeating crossbow follows the exact same design as Ming Dynasty Zhu Ge Nu. Most Qing Dynasty repeating crossbows have single piece bamboo or wooden prod, or prod made of several flat strips of bamboo lashed together. Many Qing repeating crossbow shoots fletchless bolts, sometimes jokingly referred to as “chopsticks” by contemporary Chinese people,

although exceptions do exist.

Note that the term "Zhu Ge Nu" was rarely used during the Qing period. Repeating crossbow was known as

Nu Gong (弩弓, crossbow), as it was the only type of crossbow that saw regular (albeit still extremely uncommon) military service in the Qing army.

|

| An eighteenth century Qing Dynasty double-shot repeating crossbow. |

|

| An eighteenth century Qing Dynasty Lian Zhu Nu. It can still shoot normal bolts. |

Several variants of repeating crossbow, including a double-shot variant and a stone bow variant known as

Dan Nu (彈弩, bullet crossbow) or

Lian Zhu Nu (連珠弩, lit. 'Rapid bead crossbow'), were developed during Qing period

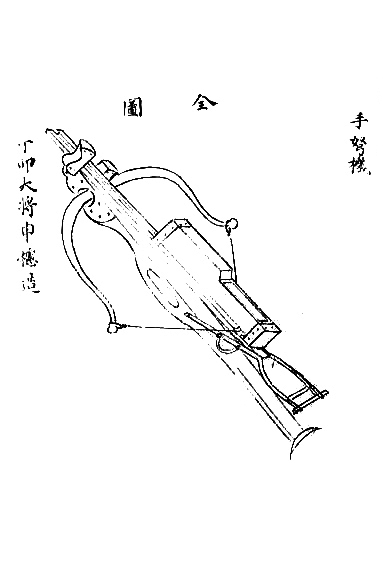

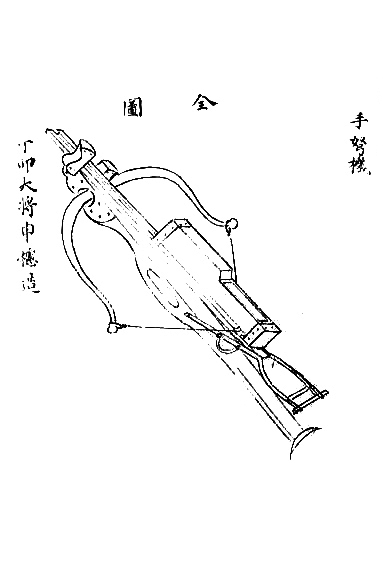

Korean Repeating Crossbow

|

| Drawing of a Sunogi, from nineteenth century 'Hungug Sinjo Gigye Doseol (《훈국신조기계도설》 or 《訓局新造器械圖說》)'. |

Korean version of repeating crossbow can be called a

Suno (수노 or 手弩, hand crossbow),

Sunogung (수노기 or 手弩弓, hand crossbow) or

Sunogi (수노기 or 手弩機, lit. 'Hand crossbow machine') and follows the same basic design as Chinese Zhu Ge Nu. Nevertheless, Sunogi has several modifications that set it apart from, and arguably make it superior to, the Chinese version.

|

| Replica Sunogi in cocked position. Note the upward-tilted prod. |

One immediately noticeable feature of the Sunogi is that it has longer tiller (stock) than Chinese Zhu Ge Nu, and its lever and magazine are mounted closer to the butt. This allows for longer powerstroke and higher velocity arrows. To compensate for longer distance between the string and the notch of the spanning lever, Sunogi's prod is mounted in such a way that its limbs will pivot upward when the lever is cocked. The overall larger size of Korean repeating crossbow also allows a more powerful composite recurve prod (basically a modified Korean bow) to be used. Like Ming Dynasty Zhu Ge Nu, Korean repeating crossbow shoots fletched arrows.

Koreans had their own variant designs of Sunogi, including

Tanno (탄노 or 彈弩), the stone bow version of Sunogi, as well as

Samsisunogi (삼시수노기 or 三矢手弩機), a triple-shot repeating crossbow.

Just out of curiosity, what would have been the main reasons why the Zhu Ge Nu was seen as an 'ineffective battlefield weapon'?

ReplyDelete@Nate The Aussie

ReplyDeleteGood day and welcome to my blog!

Zhu Ge Nu is very inaccurate (you can't aim the weapon as it is fired from the hip), has short range, and weak in power/penetration.

Poison arrow helps a little with the killing efficiency. However, most poisons won't be immediately fatal, bleeding (from the arrow wound) usually removes quite a bit of poison that went into the bloodstream, and layers of clothing usually wipe the poison coating off the arrowhead if it is shot through them.

Besides, Chinese usually use their single-shot heavy crossbows with poisoned arrow anyway.

All things considered, repeating crossbow is vastly inferior to normal bow which can achieve almost comparable shooting speed with much better accuracy and power, and China has no lack of skilled archer either, owing to its long archery tradition.

Another weapon that makes repeating crossbow redundant is the multiple rocket launcher, which is more compact, has higher rate of fire, greater power, and comes with various types of warhead.

There were depictions of naval Lian Nu that were essentially crew-served versions of the standard repeating crossbows. I'm wondering, is there more information on the larger Lian Nu versions? The hand-held Lian Nus definitely lacked sufficient power to be useful, but what about the larger versions? Could Lian Nu at crew or siege size rapidly convert muscle power to lethal projectile power?

ReplyDeleteI am not aware of any pictorial depiction of crew-served repeating crossbow except one 1941 painting depicting the event of Imjin War naval battle.

DeleteAt least one Korean source does describe a more powerful repeating crossbow, housing only five arrows but shoot farther. It is not explicitly described as "crew-served" though.

damn, it's insane how the closest thing to the lianfanu took more than 2400 years to reappear, as a recent and relevant youtuber has publicly released the plans to his constantly-upgrading "instant legolas" design - with many new features and innovations that could have been possible in ancient china as well

ReplyDeletethank you for making this insightful article!

I like Jörg Sprave, his laugh is contagious.

DeleteThe hardest part of Instant Legolas is to make the device work with a vertically-aligned bow.

Yes, i agree, that laugh is really contagious.

Deletehi, struggling to find any evidence of repeaters being used in han-tang dynasty. have you found any?

ReplyDeleteobviously the word zhuge is found in ming text but they probably confused it with a simultanous shooting crossbow instead.

only one i found is In 180 AD, Yang Xuan, but it seems to be a complicated artillery, not portable lever action ones

Indeed there isn't much records, given it's very difficult to differentiate multishot and repeating crossbow in textual records.

DeleteHello (yet) again and long time no internet communicate! Just wondering what were the poundages for the prods on these crossbows since a lot of material surrounding them seems to indicate they were pretty weak and not really for military use to the point that some writers state it's mainly a woman's or "wimpy" scholarly man's weapon.

ReplyDeleteAlso, are there any records of the civilian version of these weapons being used for hunting? I don't doubt its limited utility as a military weapon, but could see how something like this could be useful as a hunting weapon for taking certain game (especially small game like birds or rabbits or something like that).

Sorry for the multiple posts, but I had another thought occur to me after looking at the designs a bit more carefully and comparing them to my newly acquired Stinger repeating crossbow I bought designed by everyone's favorite German with addictive chuckle :P. It's kind of strange that in all these repeating crossbow designs, the shooting action and cocking action are merged into a single lever stroke when you could conceivably separate those two actions and have an actual trigger mechanism like on other Chinese crossbows or the Stinger to allow for more precise aiming and repeatable shots. Such a weapon would temporarily bypass the need to go through the cumbersome reload process of cock first, then place the bolt by hand onto crossbow as was conventional on single shot crossbows and would have a minimal loss in rate of fire vs. the other repeating crossbows mentioned here. I wonder why the ancient Chinese throughout the entire history of China didn't think to separate cocking and shooting when designing the repeating crossbow since they clearly had the technology to produce triggers and clearly had the technology to create a bolt magazine. Why did they seem keen on merging the cocking action and shooting action into one thing for repeating crossbows? Or, is there some niche ancient crossbow design not mentioned here that does play around with the idea of separating cocking and shooting and has a bolt magazine for repeatable shots I'm not aware of?

Delete@JZBAI

DeleteThat's what I used to believe as well, but in actuality Zhuge Nu was a military weapon, with records found in coastal armoury, Qing training manual etc. The only description of this weapon being a home-defence weapon comes from Tiangogn Kaiwu.

No record about its poundage or use for hunting AFAIK.

As for your second question, seriously I have no idea.

DeleteI do wonder how feasible it is to aim with a crossbow with a large box magazine jutting out on top though.

Thanks for the response. Kind of a bummer there isn't much info regarding draw weights on these weapons (especially the Sunogi since that looks like it could be quite powerful if designed properly). I would imagine it might be lower than a normal crossbow for ease of the rapid re-cocking action, but then again I could be wrong. Mandarin Mansion seems to have sold an antique ZhugeNu ( https://www.mandarinmansion.com/item/chinese-repeating-crossbow ) which he estimates to be at least 70 lbs in draw weight which even with that estimate is pretty anemic compared to European military and hunting crossbows. That poundage though might make sense for hunting certain game though which is why I asked about that earlier. The Wikipedia article on repeating crossbows seems to mention something from the Tiangong Kaiwu or Wubeizhi (not sure which source it's specifically referring to since the text of the page as always on Wikipedia is a bit vague for citations :P ) that the crossbow was used for tiger hunting. I'm a little skeptical of whether something like this could be useful for taking down a tiger given the size of the bolts being shot out of them for the smaller civilian version, even with poison (which honestly is a pretty unreliable killer) unless it's something the size of the Sunogi which for the latter would be a pretty impractical weapon to use on the hunt. I mean, perhaps the crossbow could take a boar or a small deer, but not sure about a tiger? :/

DeleteAnyway, regarding your point about aiming mentioned in the second post: the Stinger crossbow I own and mentioned previously has a magazine on top of the arrow chute (which interestingly enough has built-in iron sights on the lid) like the ZhugeNu and co. and while the magazine jutting on top does slightly mess with your aim it is actually feasible to aim with such a crossbow. Using just the iron sights and a conventional shooting stance, all you really need to do is aim slightly higher than normal or tilt the crossbow slightly to compensate for the displaced line of fire. One thing I'm noticing now about depictions of people shooting the repeating crossbow is that they seem to prefer a shooting stance akin to shooting it like a belly bow/gastraphetes and seem to hold the crossbow stock at the waist tilted upward which may be trying to compensate for the magazine on top since it clears the line of sight. It's kind of a weird shooting stance to adopt, but I guess doable especially if you use a more "instinctive shooting" mindset as was normal for traditional bows. Still makes me wonder why no separate trigger mechanism that plays no part of the cocking and bolt placing mechanism was invented since I could imagine something like a latchet crossbow-like trigger would work quite well with that set-up.

Oh well, probably shouldn't question the "wisdom" of the ancients I guess! :P

@JZBAI

DeleteSorry for the delayed reply. Been very busy lately.

- Yes, it does seem plausible that draw weight is lowered for ease of rapid action.

- As far as I can tell, Sunogi was a 18th century Korean modificatio. It was quite obsolete at that time so I doubt if it ever saw use.

- It is possible that Mandarin Mansion repeating crossbow to be a civilian version.

- Agree. I've not heard of repeating crossbow being used in tiger hunting. They were plenty of very active tiger-hunters in Southern China until (I think) around 1950s, and they mostly used modern rifles or the aptly named tiger forks.

- The poison was used against tiger though.

- Zhuge Nu was probably designed with "shooting from the hip" in mind with more emphasis of rate of fire than accuracy, as the lever is top-cranked. A repeating crossbow designed with standard shooting posture in mind will probably mount the lever at the bottom of the stock, similar to Codex Löffelholz crossbow (no magazine) or Joerg Sprave's Adder (with magazine).

Hey again. Something funny I just realized since you (and I as well) mentioned the accuracy of repeating crossbows with magazines on top and Joerg: ironically enough, he's working on getting a new crossbow model to market that happens to combine a magazine mounted below the arrow chute and is cocked similarly to the Stinger (i.e. from the back with a lever, but without needing to switch grips); the Interceptor ( https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nEE_fn3VA5U ).

DeleteAlso really funny is that there seems to be a little bit of a tussle going on between Joerg and Steambow over the Stinger platform vs. the new Interceptor platform where Steambow claims that the Interceptor would be less accurate due to the below mounted magazine. ( https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r8X3P3MKItQ ) :P

Not sure about Steambow's logic there; while as mentioned previously you could sort of compensate for the magazine jutting out via tilting the crossbow, it probably would generally be better to push the arrows up from below if possible to eliminate the problem; but I don't know, maybe there's something funky with the chute design I know nothing about that Steambow's getting on to (or not and Joerg is right and they're just trying to pimp the Stinger platform too hard :P ). Anyway, we'll just have to see when the first Interceptor models are out since I'm actually now kind of curious about this debate and the accuracy of repeating crossbows with bottom vs top mounted magazines! :3

@JZBAI

DeleteI do wonder if tilting the weapon while aiming with top magazine crossbow will create unforseen circumstances that affect accuracy as well, as (as far as I can tell) it was not done historically.