Hollywood Hallyuwood tactics

|

|

Credit where credit is due, large numbers of warships

forming complex formation has an epic feel to it, not to

mention far more visually engaging than Age of Sail-style

broadside shootout. The screenplay of the movie is

definitely superb.

|

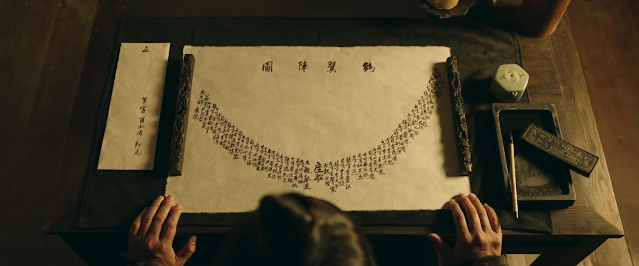

The historical Battle of Hansan Island was fought between two

roughly equal-sized navies (56 Joseon ships against 73 Japanese

ships, although the size of Japanese navy was exaggerated). Due to

superior ship design and heavier armament, Joseon navy had a massive

advantage over Japanese navy, and the resulting battle can be summed

up as "Yi Sun-sin arrayed his fleet in Hak Ik-jin (鶴翼陣, lit.

'Crane wing formation') and BAM, his tactic worked and he won the

battle. End of story.".

|

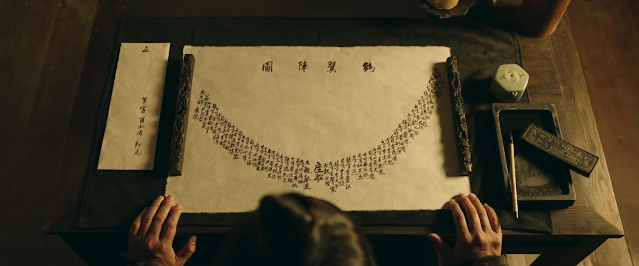

I actually quite like this scene of Yi Sun-sin writing down

the names of each of the Joseon commanders to appropriate

positions of his battle formation. It is a short but much

appreciated moment that shows Yi Sun-sin's true calibre as a

leader.

|

Obviously a story like that wouldn't work at all on the big screen, so

the director has to dial up the difficulties to make the stakes higher

and the conflict compelling. And dial up he did. Aside from the two

major historical inaccuracies mentioned above making the Japanese

threat much more severe, the antagonist Wakisaka Yasuharu also brought

in a cannon-armed, iron-hulled warship to counter Yi Sun-sin's turtle

ships, and even tried to emulate a naval version of

Battle of Mikatagahara

where Tokugawa Ieyasu's

kakuyoku-no-jin (鶴翼の陣, lit. 'Crane

wing formation', Japanese analogue to Yi Sun-sin's Hak Ik-jin, sharing

the exact same name) was defeated by Takeda Shingen's

gyorin-no-jin (魚鱗の陣, lit. 'Fish scale formation').

And

thus the stakes are successfully raised, yet new dilemmas

emerge. Firstly, raising the stakes also means that more

attention and screen time are devoted to show the ANTAGONIST'S

attempts at tackling challenge after challenge being thrown at him

from the protagonist's side. While this is entertaining to watch,

portraying the antagonist this way establishes the wrong kind of power

dynamics (can't believe the bad guys are actually the underdog!),

turning the overall narrative on its head.

Secondly, with a dangerous antagonist laser-focused on countering Yi

Sun-sin's every moves, a historically faithful recreation of his naval

tactics seems wholly inadequate to overcome the dialed-up challenge.

Yet the protagonist must win, and it's up to the director to make

sure that he did. Unfortunately, the director wrote himself into a

corner—lacking the military experience and genius of the historical

character he is trying to portray, the ideas he's come up with are

contrived and laden with issues, often requiring the antagonist to

pick up idiot ball at crucial moments to work at all (the same problem

can also be seen in China's

God of War movie I reviewed).

Two major issues will be discussed below:

The "super turtle ship" subplot

|

|

When standard turtle ship isn't cut for the job, it's time to

bust out the super turtle ship!

|

The director went to great length to show the deficiencies of the

original turtle ship, how the villain stole the blueprint to learn

about these weaknesses, how he specifically prepared an

iron-hulled warship as a counter, and how Yi Sun-sin contemplated to

not deploy his turtle ships for the climactic battle—all to

prepare the audience for the eventual grand reveal of the improved

"super" turtle ship.

In all honesty, the idea of preparing a trump card of your own to

counter enemy's ace in a hole isn't half bad, and if done well the

subplot could've culminate into an interesting and satisfying ultimate

showdown. The problem, however, is that Yi Sun-sin was no shipbuilder,

so he can only point out the problem, but not solve it himself. Thus

the role of advancing arguably the most important plot thread of the

story falls on the shoulders of shipwright Na Dae-yong (나대용 or

羅大用), a minor character with barely a dozen lines of dialogue. Zero

participation from the protagonist alone makes this subplot the

weakest part of the film.

As if that wasn't enough, the subplot was then resolved offscreen. One

moment Na Dae-yong was begging Yi Sun-sin to reconsider his decision

to not deploy turtle ships in battle, the next moment he was already

on his brand new super turtle ship, charging into battle to save the

day. How did Na Dae-yong come up with the improved design? The

audience are not told. He simply did. There isn't even any

construction montage or eureka moment in the film.

Double-loading cannons with both cannonballs and pellets

|

|

More DAKKA!

|

With a much larger fleet and a battle formation tailor-made to counter

Yi Sun-sin's own, the film's antagonist Wakisaka Yasuharu posed a

significantly larger threat compared to his historical counterpart,

necessitating some kind of new countermeasure from the protagonist's

side. However, since Battle of Hansan Island is what made famous Yi

Sun-sin's Hak Ik-jin battle formation, the director is clearly

unwilling to make drastic change to his battle formation, lest the

film strays too far from history and alienates Korean audience

familiar with the battle (which is most of them).

So the director made Yi Sun-sin come up with a novel

tactic—double-loading all cannons with both cannonballs and pellets,

sacrificing range and accuracy for sheer destructiveness—to complement

his battle formation. Now the protagonist's side can have a new trump

card against the devious tactics of their adversary, without having to

alter the iconic battle formation Yi Sun-sin was so famous for. Seems

like a great idea huh?

Well, except for the fact that this "novel" tactic isn't novel at all.

Loading a cannon with both cannonball and smaller pellets was the

standard practice of Ming artillerymen, and presumably their Joseon counterparts as well. Furthermore, it

was literally impossible for the relatively weak Joseon cannons to

decimate hundreds of Japanese ships with a single salvo, double-loaded

or no. In fact I doubt even the significantly more powerful

Hong Yi Pao (紅夷砲) could achieve that, as wooden ships are notoriously difficult

to sink.

|

|

Not gonna lie, seeing Japanese gyorin-no-jin went

against Korean Hak Ik-jin brings me immense excitement, and

in my opinion this is the high point of the second half of

the film.

|

Moreover, even if I am to assume these double-loaded cannons really

work as advertised (realism often takes a backseat to epic battle

and mayhem on the big screen), the tactic STILL wouldn't work, and

proved far more detrimental to Yi Sun Sin's Hak Ik-jin than

complement it.

This is because in order to maximise the damage his double-loaded

cannons can inflict, Yi Sun-sin ordered his entire fleet to hold

fire until the very last moment. This was a grave mistake, for it

created a highly unfavourable situation where only a dozen or so

Joseon warships plus three turtle ships were actually engaging the

massive Japanese fleet of more than one hundred ships for the

majority of the battle, while the rest of the Joseon fleet simply

sat and watched.

Thus the antagonist Wakisaka Yasuharu was handed two viable

options to victory: either he takes his sweet time to bring down the

three turtle ships (no matter how powerful, three turtle ships

without support could never win against a hundred Japanese

warships), then sweeps away the demoralised Koreans, or he can

ignore the lumbering turtle ships and charge into Joseon fleet with

his

gyorin-no-jin, splitting Joseon fleet in two in a

reminiscence of

Battle of Trafalgar. Wakisaka Yasuharu chose the second option and was actually set

for victory. Unfortunately, he was the bad guy and thus destined to

lose—at wit's end, the director simply forced Wakisaka Yasuharu to

pick up an idiot ball at the last moment to make him lose (the

protagonist MUST win no matter what after all).

|

|

Idiot ball caught in 4K: instead of maintaining the sharp

wedge of gyorin-no-jin and punch a hole through

Hak Ik-jin, Wakisaka Yasuharu suddenly ordered his fleet to

fan out to present maximum number of targets for the Koreans

to shoot at. His entire fleet was shot to pieces as a

result.

|

Other military geekery

There are a few more points about the battle that I would like to

criticise. Personally I think these are very minor problems that

won't detract from the enjoyment of the movie, but hey, I didn't

blog about Ming military all these years for nothing. Pardon me but

OF COURSE I will squint really hard at every nook and cranny for

details.

Naval ramming

While I am far from an expert in this field, the more I learned

about ancient naval warfare, the more I grew skeptical of the idea

that turtle ship was even usable in naval ramming, much less

designed for it.

|

|

Turtle ship ramming is possibly the biggest misconception

about Yi Sun-sin's naval tactics.

|

To make ramming possible at all, a strong keel to provide

longitudinal strength to the hull is mandatory, as the warship must

be able to absorb and withstand the tremendous force generated

during the moment of collision. Furthermore, warships designed for

ramming, such as the ancient galleys, tend to have a sleek profile

with narrow or pointed prow, both for speed and to minimise area of

contact in order to avoid unnecessary damage to the hull.

Unfortunately Turtle ship had all the undesirable traits of a

ramming vessel, what with being a keel-less ship with boxy hull and

wide, flat prow.

Japanese cannons in the film are HUMONGOUS, matching or possibly even

exceeding the size of the the renowned

Kunikuzushi (国崩し,

lit. 'Destroyer of provinces') siege cannon. Given Japan's artillery

deficiency during Sengoku period, it is extremely unlikely that Wakisaka

Yasuharu could procure so many heavy cannons in such a short amount of

time. It is also pretty stupid, not to mention ahistorical, to mount

heavy cannons beside the command tower of a warship.

|

|

Movie physics: somehow mounting heavy cannons weighing several

tonnes at the tallest part of a ship has zero effect on the

ships's balance or centre of gravity.

|

Even more jarring is how the Japanese handled their cannons in the

film—and I thought the

handheld mortar scene

is dumb enough. Surely the director understands standing directly

behind a cannon while it is firing is a stupendously bad idea?

|

|

Firing a cannon like this is a good way to get your entire

rib cage pulverised.

|

Anchors

|

|

Both Panokseon and Geobukseon (turtle ship) mount their

anchors directly in front of the prow.

|

It is odd that none of the ships in the film have an anchor,

despite the otherwise great attention to details. While not a

particularly serious issue, for me this is a tell-tale sign that

these ships are all CGI, and a little immersion-breaking.

Instantaneous communication

|

|

Flag signals, cool.

|

I really appreciate that the director devoted some screen time to

show how communication happens between ships, with drums, flags, and

in one case even kites being used to relay orders. Unfortunately,

while initially depicted fairly realistically, communications

between ships become drastically faster as the battle picks up pace,

and by the end of the film both protagonist and antagonist had

become essentially telepathic.

Nationalistic undertone and inflated self-importance

|

|

The tattered banner of righteous army is a nice touch of

symbolism about a just war.

|

Imjin War is portrayed as just war, a struggle between the

righteous and the wicked, of good and evil, and of everyday

Korean people against foreign invaders. The last one is part of

the reason why the director forcibly added the otherwise

unrelated Battle of Ungchi Pass into the narrative—to allow for

the participation of citizen militia in the defence of their

home country. This is not a criticism by the way, as they are

par of the course for a nationalistic film. There is nothing

wrong with depicting a defensive war as just.

Yet the film goes beyond even nationalism and into the territory

of chauvinism with the inclusion of the oft-repeated myth

about a second Japanese supply route at the west coast of Korea

(which never existed), as well as Hideyoshi's plan to bypass

Korea entirely and launch a direct naval invasion on China's

Tianjin city, which he secretly entrusted Wakisaka Yasuharu to

carry out. The sheer insanity of this fictitious plan beggars

belief. Not only is Tianjin thousands of kilometres away from

South Korea, it also sits securely inside

Bohai Bay and guarded by strategically important Shandong

peninsula and Liaodong peninsula. A direct naval invasion of

Tianjin means that Japanese fleet would have to sail for weeks

on open sea without any stopping point, into a gigantic death

trap that was the Bohai Bay, and without any hope of resupply.

Lack of drinkable water alone would've decimated most of the

fleet.

|

|

Nah, China would be just fine.

|

In summary, when making a film about history's battles, we have the chance to stuck into two situation:

ReplyDelete1/ We got a battle where our side is stronger than "evil side".

2/ We got a battle where our side is too weak that we can't cause any casualties to the "evil side".

With the director, they usually need a battle where:

+ Our side is weaker than "evil side".

+ But we have something good to defeat the enemy.

+ even if we lost, we still caused much of casualties to our enemy.

--------------------

In the reality, that "perfect battle" sometime doesn't really exist. Even the battle of Myeongnyang, we ( Korean) are 12 battleship ( + cannon) fight against 300 smaller ships which only armed with bow and matchlock rifle. It as same as the tragic battle of our enemy more than our side if Yi Su Shin doesn't got much of trouble with his soldiers' morale. - -'

In many films, director simple change everything to creat the " perfect battle" by himself. And it finally turn the story becomes something illogical.

More or less.

DeleteWith proper use of artistic license it is still possible to make a good adaptation of a historical battle where good guy is stronger than the bad guy, but it needs to be handled very very carefully.

So far as naval rams go, history has produced so very odd ones. I'd suggest checking Wikipedia for the history of the United States Ram Fleet and the First Battle of Memphis. The ships involved are rather more like Geobukseon than one might expect.

ReplyDeleteThank you for this review!

The introduction of iron hull and steam propulsion probably changed a lot of the considerations in designing a ramming ship, yet even steam rams maintain a pointed prow.

DeleteActually, the steamboats in the US ram fleet were wooden framed and wooden keeled, and the ram prow was wooden too. Some of them were protected by metal plate (ironclad were cannon-proof, more or less, while "tinclad" ships could stop a rifle bullet), some by cotton bales ("cottonclad") and some were unarmored and depended on speed and luck to survive. Seriously, it's worth looking at them, because they were accidentally quite similar to the Turtle ships. The reason they're so odd was that they were first generation technology (ironclad steamships), and the designers were working out how to fight with paddlewheeled boats.

Delete@HETEROMELES

DeleteThe considerations needed to be taken were not just about the ramming ships themselves, but their targets too.

Warhips of the time were steam-powered ironclads, so the revival of ramming was in part an attempt to defeat the hull below the water line (which was not armoured) because ironclad hulls were very resistant to cannon. Hence many steam rams had very low freeboard (nearly the entire hull is submerged underwater).

This is again in contrast with Joseon warships, being U-bottom wooden ships they had very high freeboard. This makes sense too, because taller ships are more difficult to board, and can directly shoot at the deck of a shorter ship.

Thanks, I appreciate that.

DeleteThe other consideration with the first generation ironclads is that they were shallow draft for harbors and (on the Mississippi) for shallow rivers. The Japanese ships attacking Korea had high freeboard, not just to protect against boarders, but also to make them more seaworthy. If I recall correctly, the coastal waters in Korea tend to be fairly shallow, and this was reflected in their ship design as well. A way to think of this is that the turtle ships were for coastal defense of Korea, not for crossing to Japan and raiding those coasts. If the Koreans had tried that, they probably would have capsized every turtle ship sent on the mission.

I'd simply end by pointing out that the combat steamships (all the ones of the 1800s, basically) were all experimental, trying to incorporate new technology, including steam (fuel intensive and thus short range), cannon-proof iron plate (initially so heavy that the ships could barely float, let alone move), and massive improvements in guns (which doomed naval rams by the 1880s). The resulting ships and boats look really odd to modern eyes.

I think similar things happened in Korea. And in the Ming military, for that matter.

I'll stop wasting your time, but I did want to thank you for spending so much effort on this really informative blog. I've learned quite a lot reading it.

Were the Righteous Armies really that affective against the invading Japanese? Or is it just nationalist wishful thinking? a way for the Koreans to alleviate some sort of guilt for not (initially) resisting the Japanese more vigorously? and a way to downplay the Ming contribution, I've heard some Korean nationalists say the Chinese were not even needed as they would have defeated the Japanese without Ming intervention. Historically we know armed civilian resistance didn't play a big role in defeating an occupying power, whether it is the Spanish guerillas resisting the Napoleonic French, or the French resistance and the partisans in Russia against the Nazis, or the Vietcong against the Americans. I would think the Righteous Armies proved to more of an annoyance to the Japanese than a threat, it took organized and experienced armies of the Ming and regular Korean military to fight and defeat the Japanese.

ReplyDelete@Der

Delete"Were the Righteous Armies really that effective against the invading Japanese?"

They did better than Joseon regular army, at least.

"Or is it just nationalist wishful thinking? a way for the Koreans to alleviate some sort of guilt for not (initially) resisting the Japanese more vigorously?"

Rather than guilt, I think it's to depict the contribution of "we the people" in resisting foreign invaders, since it's easier for the average audience to resonate with common people than larger-than-life heroes of distant past.

"a way to downplay the Ming contribution"

As far as this movie is concerned, Ming wasn't involved yet, so there's nothing to downplay.

"I've heard some Korean nationalists say the Chinese were not even needed as they would have defeated the Japanese without Ming intervention."

Of course. That's what you should expect from nationalists.

"Historically we know armed civilian resistance didn't play a big role in defeating an occupying power."

Most of the time, this is true but exceptions do exist though. Ming Dynasty was founded that way.

"I would think the Righteous Armies proved to more of an annoyance to the Japanese than a threat"

They were a pretty big annoyance to say the least, but yes, not a decisive threat to the Japanese. Doesn't help that Joseon government treated them like sh*t.