The second part of this series will provide an overview on various components of Chinese gate, as well as their names. As before, italicised names are likely modern terminology.

Cheng Men (城門, lit. 'Wall gate')

As with all fortifications around the world, the gate is the most vulnerable—and often the most heavily fortified—part of a Chinese city. The Chinese term Cheng Men can refer to both the gate door itself, as well as the gatehouse securing the entrance. For clarity's sake I will separate gatehouse, gateway tunnel, and gate doors into three sections.

Gatehouse

|

| Zhonghua Gatehouse of the city wall of Nanjing. |

The term "gatehouse" is actually a misnomer, as a typical Chinese gatehouse is a relatively featureless block of rammed earth and bricks, with one or several gateways tunnelled through it. Most of the defensive features of a Chinese gatehouse are taken up by the guard tower built on top of it.

One notable difference between Chinese and European castle gatehouse design is that flanking towers were rarely used by Chinese people to bolster the defence of their gatehouses. This is largely due to the fact that the primary function of flanking towers can be better fulfilled by Weng Cheng (see below), although hat is not to say flanking towers were never used.

|

| The gate of Jimingyi fortified postal/relay station is a rare example of a Chinese gatehouse with prominent flanking bastions. |

Gateway Tunnel

Early Chinese gateway tunnels were trapezoidal in shape and used wooden columns and lintels to support the structural integrity of the entire tunnel. However, such design was extremely vulnerable to fire, so it was quickly superseded by the more robust arched tunnel as soon as Chinese people figured out how to build a stone

arch. As such, most surviving Chinese city gates today have arched tunnels.

|

| Section of the Song-period painting "Along the River During the Qingming Festival", depicting a trapezoid gateway. |

Owing to its large size, a Chinese gatehouse has fairly deep gateway tunnel. Gate doors are usually (but not always) placed deep inside the tunnel to protect them against the elements as well as indirect fire artillery. However, if the enemy get into the tunnel and start battering down the doors, little can be done by the defenders on the wall to force them out. To mitigate this issue, gateway tunnels of larger gatehouses typically contain smaller branch tunnels that connect to

Cang Bing Dong (藏兵洞).

|

| Cang Bing Dong inside the gateway tunnel of Zhonghua Gate. |

Gate Doors

Despite its rather inconspicuous appearance in comparison to the massive walls and majestic towers, Chinese gate door is actually incredibly sophisticated and complex.

|

| Front (left) and back (right) side of Chinese doors, Forbidden City. |

A typical Chinese gate door is a heavy wooden door, almost always rectangular in shape, and of the

Shi Ta Men (實榻門, lit. 'Solid-bed door') type construction. Outwardly, it is not too dissimilar to a typical ledged door. However, instead of simply securing the ledges to the boards by means of nails and metal bracing, the ledges of a Chinese door are directly slotted into the boards with

sliding dovetail joints and secured from the sides with

mortice and tenon joints, which make for a very strong door. Due to its large size, Chinese gate door is not hinged to a frame, instead it is built as pivot door.

Ledges of a Chinese gate door are usually reinforced with metal door nails from the side facing outward. Door nails found on ornate or important gate doors (such as the gate doors of Forbidden City) tend to have enormous dome-shaped caps (some nail caps can be as large as, or even larger than, the fist of an adult male), said to help in retaining the mud used to fireproof the doors. Smaller and more utilitarian gate doors (such as the gate doors of Shanhai Pass) have sensibly-sized door nails, however.

|

| Two gilded door nails. |

From Song Dynasty onward, most Chinese gate doors were further reinforced with heavy iron plating, although precious few of these reinforced doors survive to the present.

|

| Surviving Qing period doors of Chengen Gate of Taipei, with still-visible iron plates on the top portion of the doors. |

Que (闕)

|

| Que "wings" of the Meridian Gate of the Forbidden City. |

Also known as

Que Men (闕門) and very rarely

Guan (觀), Que refers to a type of

ancient ceremonial gate tower commonly found at the gateways of palaces, temples, tombs and bridges. Originally built as free-standing towers, by later period Que towers were usually fused into the gatehouse building to form a single U-shaped structure.

The number of Que tower may change depending on the symbolic significance and prestige of its associated building. Most forms of Que towers only have two single towers—one on each side, while Que towers used by nobilities or high ranking government officials, known as

Er Chu Que (二出闕) or

Mu Zi Que (母子闕, lit. 'Mother-and-son Que'), have two adjoining towers on each side. The most prestigious version reserved for the emperor, known as

San Chu Que (三出闕), have three adjoining towers on each side.

2.1) Gatehouse facilities

Cha Ban (插版, lit. 'Slotting plank')

|

| A Cha Ban half-concealed inside the groove of a gateway tunnel. Gonghua Fortress, Beijing. |

More properly known as

Zha Ban (閘板, lit. 'Floodgate plank'),

Gan Ge Ban (干戈板, lit. 'Conflict plank'),

Cha Bei (槎碑, can be roughly translated into 'raft stele'), and less formally as

Qian Jin Zha (千斤閘, lit. 'Thousand

jin floodgate'), this is the Chinese equivalent of portcullis. Unlike European-style portcullis, which is typically constructed as a metal latticed grille, Chinese Cha Ban is built similarly to normal gate door but even more heavily armoured/reinforced, as it is actually expected to function as a floodgate.

Wu Xing Chi (五星池, lit. 'Five star pond')

Wu Xing Chi is a special ditch, somewhat similar to a manger/watering trough, that is built directly above the gate doors, with up to five drain holes inside. Its primary purpose is to allow the defenders on the wall to put out fire inside the gateway tunnel (especially if the gate doors catch fire), although the defenders can just as easily pour other harmful liquid down the ditch onto unsuspecting attackers inside the tunnel. One advantage of Wu Xing Chi over regular murder hole is that it allows the defenders to simply pour harmful liquid into the ditch without having to look for a specific murder hole (as handling and pouring dangerous/hot liquid down a regular-sized murder hole can get messy really quickly amidst the chaos of war).

|

| Sloppy illustration of a Wu Xing Chi, from 'Wu Bei Zhi (《武備志》)'. The murder holes actually point downward, not sideways like the illustration. |

Despite the importance of murder hole in the defence of a fortification, surprisingly few Chinese city gates are equipped with it. In fact, only a handful of Chinese gates have murder holes at all.

|

| Ordinary murder holes (NOT Wu Xing Chi) of Pan Gate, Suzhou, viewed from above (left), and viewed from inside gateway tunnel (right). To my knowledge, Pan Gate is the only surviving Chinese city gate with regular murder holes. |

Tian Chuang (天窗, lit. 'Sky-window')

|

| Gate of the city wall of Linhai. The circled part is a Tian Chuang. Under normal circumstance, it would be hidden by the arrow tower. |

Tian Chuang, also known as

Tian Jing (not to be confused with the

loophole of the same name

), is another Chinese counterpart to murder hole. Tian Chuang is much larger than regular murder hole and Wu Xing Chi, and unilke regular murder holes can be found both in front of and behind the gate doors, Tian Chuang is always built behind gate doors.

While perfectly functional as a murder hole, it is suggested that the primary purpose of Tian Chuang is actually flood control. During a flood, the gate doors would be closed and Cha Ban lowered. Tian Chuang allows flood workers to fill the empty space between gate doors and Cha Ban with earth (or sandbags in more recent times) to prevent the breaching of gate doors.

|

| Various views of a Tian Chuang. |

2.2) Barbicans and Outworks

Weng Cheng (甕城, lit. 'Urn fort')

|

| Left: Outer Weng Cheng of the eastern gate of Jingzhou city wall. Right: Triple inner Weng Cheng of the southern gate of Nanjing city wall. |

Considered the cream of the crop of Chinese fortification, Weng Cheng is a fortified wall that completely encloses the gatehouse. It is typically rectangular or semicircular in shape, and can enclose the gatehouse from either outside or inside (a few gates have both outer and inner Weng Cheng). The wall of Weng Cheng is usually built to the same height and thickness as the main city wall, and comes complete with its own battlement, gatehouse and tower. Barring a few exceptions (i.e. capital cities like Nanjing and Beijing), the gate of Weng Cheng is always intentionally misaligned from both city gate and drawbridge in order to force enemy troops and siege engines to change direction multiple times before they can reach the main gate.

While usually translated as '

barbican' in English, Weng Cheng actually differs from most forms of castle barbican in design and purpose. A typical barbican is a fortified outpost designed to bolster the defence of a castle entrance and seeks to deter enemy troops from ever reaching the gatehouse. To this end, it is usually built outside the principal fortification limits and only connected to the gatehouse via drawbridge or a raised/walled corridor dubbed "the neck". The neck prevents enemy troops from storming the gate

en masse, as moving a large body of troops across such a narrow passage in a short time is all but impossible, although this also prevents the defenders from sortie out to meet their enemies head on.

On the other hand, Weng Cheng is designed to delay enemy assault and, whenever the chance presents itself, lure a portion of enemy troops inside, separate them from the main body of the army, and annihilate them. As such, Weng Cheng is much more spacious than barbican, allowing more troops to get in or out at once. It can also act as a staging ground for the defenders that want to engage their enemies directly.

In some rare cases, a Weng Cheng can also be detached from the main wall and made into a fortlet/proper barbican.

|

| A Ming period map of the Song-era triple cities of Yangzhou, showing the layout of multiple detached Weng Cheng. The city walls have all but disappeared by now, although a few Weng Cheng survive to this day. The circled portion of the map shows the western gate and Weng Cheng of the smaller Jiacheng city (the map is oriented westside-up), and the photo at the right shows how they look today. |

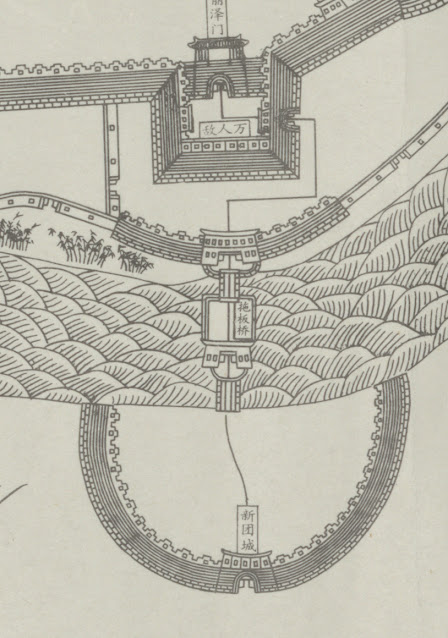

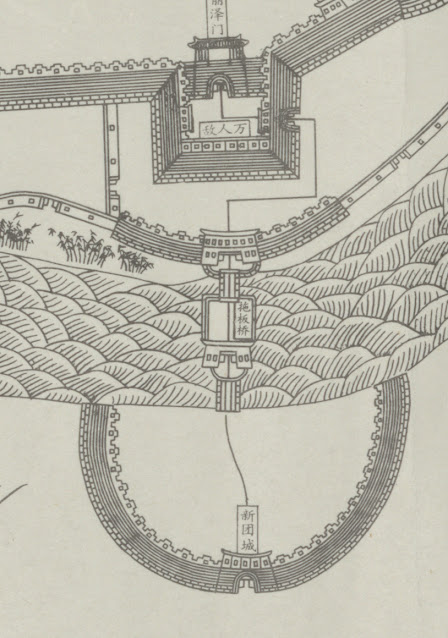

Yue Cheng (月城, lit. 'Moon wall')

|

| A Yue Cheng guarding a floodgate-bridge. Image cropped from 'Jing Jiang Fu Cheng Chi Tu (《靜江府城池圖》)', a Song Dynasty city map of Jingjiang (present-day Guilin City) carved into the cliff of Parrot Mountain. |

Yue Cheng originally referred to a type of advanced work that is basically a semicircular fortified wall that encloses a portion of a moat or river and serves as a permanent fortified bridgehead. Definition of the term changed over time, and eventually a new type of fortification also came to be known as Yue Cheng. This second type of Yue Cheng is a fortified wall that encloses the gatehouse of a Weng Cheng, essentially functions as a secondary Weng Cheng. Unlike a proper Weng Cheng, the wall of Yue Cheng is thinner and lower than main city wall, allowing defenders on both walls to engage the enemies at the same time.

|

| Yue Cheng of the restored city gate of Zheng Ding. |

Hu Men Qiang (護門牆, lit. 'Door-protecting wall')

|

| A small Hu Men Qiang in front of the east gate of Jiminyi fortified postal/relay station, blocking the view of the gate. Properly fortified Hu Men Qiang can be nearly as large as the main wall itself. |

Also known as

Dang Men Qiang (擋門牆, lit. 'Door-blocking wall') and less commonly

Yong Men (壅門, lit. 'Block door'), Hu Men Qiang is a solitary wall built in front of a city gate without Weng Cheng to hide the gate from enemy observation, as well as protect the gate doors against direct bombardment. Essentially a fortified

spirit screen enlarged to city scale, Hu Men Qiang is usually built on top of a

Que Tai (鵲臺) some distance away from the city gate. During wartime, both sides of Hu Meng Qiang can be barricaded with wooden palisades, enclosing the gatehouse entirely.

|

| Semicircular chemise protecting the west gate of Hwaseong Fortress in Korea. While Koreans call the chemise Ongseong (옹성), equivalent to Chinese Weng Cheng, it is actually closer to a Hu Meng Qiang in Chinese classification. |

2.3) Buildings on the Gatehouse

Cheng Lou (城樓, lit. 'City tower')

|

| Front view of the Cheng Lou of Zhengyang Gate, Beijing. |

Cheng Lou or

Zhong Men Da Lou (重門大樓, lit. 'Great tower of heavy gate') refers to the great tower sitting on top of the main gatehouse of a city. Unlike other

defensive towers on the wall, Cheng Lou primarily serves as a command and observation platform and is built to impress. As such, it typically lacks the fortified brick structure and loopholes of its more defence-oriented counterparts.

Zha Lou (閘樓, lit. 'Floodgate tower')

|

| Zha Lou of the southern gate of Xi'an. |

Zha Lou refers to a gate tower that houses the facility to control Cha Ban/portcullis, and sometimes the drawbridge as well. It is typically built on top of the gatehouse of a Weng Cheng or Yue Cheng.

Diao Qiao (釣橋, lit. 'Angling bridge')

|

| Raised drawbridge of the southern gate of Xi'an. |

Diao Qiao is the Chinese term for drawbridge. Due to the massive size of Chinese moat, a single wooden drawbridge that spans the entire width of the moat is highly impractical. Instead, drawbridge is typically built at the narrowest point of the moat. Alternatively, a fortified artificial islet can be erected at the midpoint of the moat, with two drawbridges connecting the gatehouse to the islet, and islet to the other side of the moat.

It should be noted that the correct historical term for drawbridge is

Diao Qiao (釣橋, lit.'Angling bridge'), which is not to be confused with

Diao Qiao (吊橋, lit. 'Hanging bridge') or suspension bridge. However in common/modern usage

Diao Qiao (吊橋) can be used to refer to both drawbridge and suspension bridge.

3) Moat

The third part of this series will provide an overview on a moat and its related facilities, as well as their names. As before,

italicised names are likely modern terminology.

Hao (壕, lit. 'Moat')

|

| The moat of Xi'an. |

Hao is the Chinese term for moat. It is also known as

Hu Cheng He (護城河, lit. 'City-protecting river'). As Chinese people built some of the largest and most impressive fortifications in the world, they also dug some of the deepest and widest moats to match their forts. In addition to military purpose, moats also serve an important role in flood control.

A dry moat is known as

Gan Hao (干壕) or

Huang (隍).

3.1) Moat Walls

Yang Ma Qiang (羊馬牆, lit. 'Sheep and horse wall')

|

| Drawing of Yang Ma Qiang (highlighted), from 'Wu Bei Zhi (《武備志》)'. |

Also known as

Niu Ma Qiang (牛馬牆, lit. 'Cow and horse wall') and less commonly

Feng Yuan (馮垣), Yang Ma Qiang refers to a small moat wall, or

fausse-braye, built on top of a

Que Tai (鵲臺) near the bank of a moat (although some moatless cities also have Yang Ma Qiang). Originally designed as a temporary shelter for refugees' livestock in time of war (to avoid congestion of the city gate), before long Yang Ma Qiang was also fortified and installed with an assortment of loopholes and turned into a secondary defensive wall, allowing defenders of two walls to engage the attackers at the same time.

|

| An old photo of the Anding Gate of Beijing. The small wall maked with a red arrow is a Yang Ma Qiang. |

Yang Ma Qiang also serves as an obstacle that prevents enemy siege engine from getting too close to the main wall.

Hu Xian Qiang (護險牆, lit. 'Danger-protecting wall')

|

| Comparison between Yang Ma Qiang (left) and Hu Xian Qiang (right). Image cropped from 'Jing Jiang Fu Cheng Fang Tu (《靜江府城防圖》)'. |

Like Yang Ma Qiang, Hu Xian Qiang is also a defensive wall built near the bank of a moat. Whereas Yang Ma Qiang is a relatively thin parapet, Hu Xian Qiang is a full-fledged (albeit smaller than the main city wall) fortified wall with its own battlement, towers and gates.

Another wonderful article. Can't wait to see more.

ReplyDeleteWow,nice article. For years I have been trying to research whether Chinese fortifications utilized portculis similar to Europe and if so, why there was never a latticed grille portculis used observed in any of the Chinese gates in China.

ReplyDeleteNow I know why, for multipurpose use as a floodgate.

Maybe it is a lack of understanding, but one thing i observed from part 1 is the lack of 'jettying'/machicolation in Chinese fortifications. Which could be useful in engaging the sieging forces directly below the wall. It seems like the sky-well design doesn't offer the same range of attack options for the defender for that blind spot and the portholes are somewhat small.

Is there a particular reason why?

Good observation. There is indeed no Chinese equivalent of machicolation (the improved Xuan Yan is the closest equivalent), at least not on surviving walls, even though such feature can be found on Indian and Japanese fortifications.

DeleteTo be honest I don't exactly know the reason.

One may speculate, what on most surviving chinese walls bastions fulfill the same function(by the means of mutual coverage).

DeleteThis is my own stab in the dark.

ReplyDeleteThere is no such thing as a blindspot, for the defender or the besieger. What the machicolation allowed though was the ability for the wall defender to engage with the enemy, giving them no respite at the base of the wall.

An analogy would be always having a chess piece to threaten any pawn that makes it to the other side of the board end.

However, that also means that the besieger can also shoot back. Also I have observed that the machicolation holes aren't usually tapered if at all. Meaning there is equal range for both sides to shoot through the hole.

What I did notice is that generally Chinese fortifications had an extra brick jutting out as well as the fact that the walls tended to be thick and sloped unlike e.g. Indian and European walls. Was that a byproduct or purposeful design to deny the enemy space to breathe under the wall? It does seem like the Chinese wall design preferred to not have the hassle of machicolation at all. I do find it hard to believe that the Chinese would have no exposure or concept of the advantages of machicolation as shown with the Chinese hoarding design in part 1 of Chinese fortifications or the fact they would've been exposed to this sort of Castle opening board design with the Japanese.

I don't quite understand the "extra brick jutting" part, can you elaborate? With a picture preferrably.

DeleteHowever, the concern about enemy troops shooting back is a valid one. If you compare Ming-Qing battlement with Song Dynasty battlement, you will notice that the majority of Ming-Qing merlons have no Duo Yan (loophole in the merlon) due to the concern that it might put defending troops at risk.

I've read that it is possible (even advisable) to install machicolation on the top of a sloped wall though. It is said that the stone dropped from machicolation will hit the sloped part (talus) of the wall and shatter on impact, sending stone fragments everywhere.

It should be noted that Chinese fortifications are mostly just walls. For the most part, the "blind spot" at the base of a wall can be taken care of by adjacent bastions.

DeleteThis is also a stab in the dark: I *suspect* battlements with machicolations are less sturdy than those without and much more vulnerable to stone thrower, since they are thinner, jut out from the wall/tower (i.e. easier to hit) and are supported solely by corbels. I am no structural engineer so don't quote me on this though.

For this reason it is unusual to find machicolation installed on wall, even in Europe. From what I can tell from internet pictures, neither Constantinople, nor Carcassonne, nor Dubrovnik, nor Ávila, nor Toledo have it on their walls. There are some notable exceptions like Avignon though.

I think you're onto something with the sturdiness argument. Medieval european fortifications tended to have taller profiles and used machicolations somewhat. As time went on into 16-17th centuries, star forts etc had wider and thicker walls instead of their taller and thinner counterparts to resist gunpowder artillery, and also did not employ machicolations for the most part. I think it's reasonable to say the wide use of heavy artillery at least is a factor to discourage constructing machicolations.

DeleteSorry, I looked more closely and the slight amount of brick sticking out just below the battlement wall probably has nothing to do with fortifications defense. My mistake.

ReplyDeleteThe brick jutting out just below the loopholes for the Jingzhou bastion

https://1.bp.blogspot.com/--eFcdgJXEXQ/XQj-xsD9fnI/AAAAAAAAFL0/WRt51q5c4skAqXFpX1LvSonUW-QM_wmvACLcBGAs/s1600/863f91c182504f67aef78e60103e47880.jpg

https://imgur.com/a/T8jaHfH

It just stuck out to me when looking at non-Chinese walls which tend to be smooth.

Great post! I recently filmed a youtube video looking at Juyong Pass on the great wall and there are some interesting things to note with regards to this post. The original video can be found here for those who are interested: https://youtu.be/TXmlTZhry_w

ReplyDeleteThe top of the northernmost gateway had 五星池 though I was unaware of this name and simply called them “murder holes” at the time.

The roughness of many chinese walls is likely due to the fact that they have been continually built upon and destroyed. Many walls at Juyong Pass are good examples of this. In general a whole wall of structure with flat consistent stonework is likely modern, while more haphazard looking masonry is a wall which may have older and younger pieces stacked together.

Also, i briefly mention the issue of machicolations in the video. Basically I believe that it would be very difficult to make a strong rammed earth wall which did not have a slope to it, and the slope on many of these walls allows defenders to fire down at the base of the wall with bows, crossbows, or gunpowder weapons, so the machicolation likely wasn’t necessary. A defender may be safer shooting down from behind a machicolation than peaking down at the base of the wall from flat battlements, but I am not sure it machicolations would be worth the extra effort to construct.

OMG I can't believe there's actually a surviving 五星池! Thank you for finding it!

DeleteBTW, can I use the screenshot of 五星池 in this article?

DeleteYeah sure thing!

DeleteDoes anyone have an image of the winching mechanism of the lowered portcullis?

ReplyDeleteI did find an image described as "portcullis that couldbe lowered over a chinese gateway in the event of the gate being destroyed japan archive" in the online google book of Siege Weapons of the Far East (1): AD 612–1300 by Stephen Turnbull

https://imgur.com/nEsU1xG

https://books.google.com.au/books?id=k9sbDAAAQBAJ&pg=PA6&lpg=PA6&dq=portcullis+that+could+be+lowered+over+a+chinese+gateway+in+the+event+of+the+gate+being+destroyed+japan+archive&source=bl&ots=VyRpGRptZU&sig=ACfU3U3-ci0SY4S7aNq_r3F7ztyyFwb6kw&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiBmbvTu-LpAhUM6XMBHSVLC8IQ6AEwAHoECAoQAQ#v=onepage&q=portcullis%20that%20could%20be%20lowered%20over%20a%20chinese%20gateway%20in%20the%20event%20of%20the%20gate%20being%20destroyed%20japan%20archive&f=false

https://baike.so.com/doc/6342619-6556239.html

DeleteIt seems like 'experts' know much about the weight and distance dimensions of the portcullis, in this example the Arrow tower sluic gate of Jianlou.

But according the link even they do not know how it works. How is it that this would be lost in time considering the importance of flood control throughout history up to the present for a great many urban centres during the Qing dynasty as they struggle with flood water management?

@Khai

DeleteI guess it's not that these experts can't make a mechanism that works, rather they are uncertain which one is the most historically accurate/plausible design.

Or they just don't care. Maybe.

Hi, did a bit more digging with some luck I found some images. Accuracy like you said, don't know.

ReplyDeleteNot sure if these images are useful or not.

A tourist's photos of Panmen City Gate (Suzhou)

https://imgur.com/q4jxWIU

https://imgur.com/xbza11R

https://imgur.com/GuH7RB5

https://imgur.com/0rZuzRr

I suspect that one is a modern "reconstruction".

DeleteOne Ming period painting I find shows the portcullis slot but not the mechanism.

https://i.imgur.com/s0jwZib.jpg

Amazing you were able to find that painting. Most paintings I found just show the floodgate. Like you said, I don't think they cared.

ReplyDeleteSorry but I am just absolutely fascinated/obsessed with China's hydraulic engineering history. I promise this is the last comment about this.

I found another modern reconstruction, a scaled model of Zhengyang gate, Beijing.

I just wish there were some primary references for the scale models.

https://imgur.com/rHfD6IX

This is the portcullis winching mechanism of Zhengyang Gate in Beijing.

Unlike the first link I showed, it doesn't seem to have two extra support poles for extra safety in case the rope slipped from the wincher.

@Khal

DeleteIt's okay to discuss any topic in this blog, as long as everyone keep the discussion civil and polite. However, there may be topics that I am unfamiliar with and can't help much.

The "expert" reconstruction of Zhengyang Gate (3D model from your initial comment) mechanism seems to be based on an mostly complete surviving mechanism (although certain auxiliary parts alread rot off) as well as investigating signs of wears on the mechanism itself. I think it's the best reconstruction so far.

It's the first time I've seen this newest pic. I think it depicts a similar mechanism to the 3D model. Maybe the modeller omitted the support pole due to size limitation?

I don't know. I know they based the rest of the model on remaining old beijing walls and photos.

ReplyDeleteI actually don't anyone online so-far that knows much about the winching design. I suspect that it is not unknown just not available OR like you said earlier it's about find the most accurate original design. After all I can hypothesise that the same similar design and basic mechanism employed in many other cities or hydraulics works in general.

The emphasis has always been on the old Beijing walls themselves. Unfortunately this is not the exception. I have no idea whether they did it on a whim for the design or they actually researched exhaustively before making the winching mechanism. That's what is so frustrating about all these modern reconstructions.

I know that the 3d model (Zhengyang Gate Arrow Tower) would've require a more robust design because of the weight and material dimensions of the metal plank door, supposedly the heaviest portcullis in China at the time. But I don't see why the newest pic shouldn't have safety beams inside the horizontal winch columns.

I also look at other surviving working portcullis in Europe, I don't really understand why there aren't surviving clues as to how a door was permanently held up by some locking system like gears resting against a block. E.g. like a Chinese crossbow trigger rest?

Anyways good chat.

Apparently the Zhengyang Gate portcullis was held up and sealded off for so long that the winch mechanism to lower it rot away, hence the difficulties in reconstruting it.

DeleteHi, I think I found a description of how a type of winching system (not sure if all designs accounted for) of a city flood plank. Now does it describe everything and accurately with archeological findings? Not sure. But at least it is a manual that describes the lifting system. Seems simple with no counter weights (stone or drawbridge), or use of gears or additional pulleys. I wonder if you could tell me if it is considered accurate?

ReplyDeleteActually the mechanical system seems to very much mirror the other illustrations on this blog like cranes, observation towers, siege defense etc.

What I find interesting is how different the illustration and the description differed from my first link (3d model) with no mention of the vertical columns or how similar it was to the scaled reconstruction without the pulleys.

It seems like conversion to horizontal winching might be supported by the wearing evidence. Hence the Panmen gate winching is indeed a modern reconstruction guess?

https://imgur.com/fZTiiO0

It is from the Gujin Tushu Jicheng (古今圖書集成) compiled during Kangxi and Yongzheng.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gujin_Tushu_Jicheng

槎碑圖說

槎碑量其城門高下闊窄,堅木造之,厚四五寸,外用 鐵葉排釘錠裹城上照門。洞之中挖一尺闊長渠,將 此槎預為懸穿。城上兩邊栽壯木二根,橫架圓木一 根,中安二滑車。槎碑用粗繩繫住。若遇焚門之患,土 壅不及,將槎放下阻隔。

Here are the websites, it also has some images of siege defense weapons on it. I wonder if they are useful for this blog?

https://zh.wikisource.org/wiki/欽定古今圖書集成/經濟彙編/戎政典/第296卷

https://kknews.cc/culture/y8povan.html

The second link has a pretty interesting illustration showing the siege defenders ready with prepared caltrops, sapper tunnels, counter-tunnels, observation tower, horse traps (ditches?) and mobile fences to impede the attackers.

Hopefully, maybe at least this comment might've been informative or had some information you could use outside this discussion.

Great find. I am aware of this mechanism, although it only shows the most basic princlple/configuration.

DeleteThe second link only throws up a list of random weapons without giving any relevant context. My own article about siege defense (still WIP) is much better.

Thanks for writing these two amazing articles!

ReplyDeleteI am coming largely from a background in European fortification here but I wonder what some of the design philosophy or underlying reasons for many of these features were. Would you allow me to pick your brain a little?

For example judging by some estimated populations and surface area of Tang and Song dynasty cities the population density was rather low compared to European cities. From where I am standing this would suggest a much greater length of wall was needed to surround a large Chinese city compared to an equivalent sized European city. Was this accounted for by having a large garrison force or did it simply not prove an issue because sieges focused on only a small section of the wall?

In case they had a comparable garrison did the garrison move about rapidly from one place to another to cover the defenses?

Again coming from a European background here the extremely wide chemin de ronde really stands out along with the apparent focus on bastions of similar height as the wall and no towers segmenting or dividing the walls to interrupt movement.

In cities in Europe they usually tried to keep a clear path or lane behind the walls to facilitate troop movement. The chemin de ronde sometimes seems to have been kept very narrow to prevent large forces of enemies gathering there and it becoming a fighting platform. Towers which stood quite a bit higher than the wall often interrupted the chemin de ronde so that people who managed to capture on section of the wall could not move and were subject to a barrage from the adjoining towers. Said towers also seem to have been placed a lot closer to each other than the bastions on Chinese walls.

I am thinking out loud here but it looks as if many of the Chinese city walls took the opposite route. A very wide uninterrupted chemin de ronde which I suppose could act as a fighting platform and would allow infantry or maybe even cavalry to rapidly move to another section of the wall.

Could you think of another reason why the walls incorporated bastions rather than raised towers for large sections of the walls and why these were situated at quite a distance? Were there traditional defensive weapons which could easily cover the gap?

Lastly, what are the qualities of rammed earth like? Did it stand up well to mining attempts or did it crumble easily? I read about a hen picking it to see if it made a dent was used as a mark of quality but did that mean it was a rather soft material or that it was harder (and perhaps more brittle)?

I am sorry if this all seemed a bit incoherent, it is quite late over here but I just had to comment ;)

Cheers!

Good day and welcome to my blog!

ReplyDeleteI must admit Tang-Song period aren't my focus, so keep in mind that my answers are also speculation.

Using Chang'an (Capital of Tang Dynasty) as an example, it had roughly the same population as Constantinople, but quite a bit larger (Chang'an was 84 square kilometer versus Constantinople's 14 square kilometer). So indeed population density would be lower.

Chang'an walls were shorter (5 m compared to Theodosian's 18m) but thicker (12 m compared to Theodosian's 6 m). Chang'an walls were much longer (37 km compared to Theodosian's 5.7 km), but it was enclosed on all sides while Theodosian Walls only enclose the city on one side.

Chang'an was garrisoned by the Forbidden Army, with a standing strength of 100,000 (60,000 permanent garrison, 40,000 on rotational shift). Constantinople's garrison was relatively modest, only 15,000.

Obviously the defence of both cities would be bulked up by levies and other armies in the vincinity during wartime, but given the manpower difference, I think it was possible to man the entire wall during siege. There ought to be some mobile elements among the defenders that move about to reinforce a weakened section, but that's only speculation on my part.

Thanks for the reply!

DeleteAfaic the total perimeter of the walls of Constantinople is 18 to 19 kilometers but much of it only had to be lightly guarded most of the time. Although the attacks on the sea side by Crusaders meant it had to be protected.

The garrison size makes sense. Do we have any date from the Tang, or later Ming, on how many people (i.e. what percentage) were actually designated garrison troops?

Having said that, I wouldn't call Chang'an an "impenetrable fortress" type city. In fact, it was probably the least defensible capital of all the Chinese dynasties.

DeleteUnlike Constantinople, for the most part Chang'an wasn't really at risk of being attacked/captured, and capturing it won't end the empire. Most of Chang'an's defensive needs were taken up by the four major passes (Dasan pass, Tongguan/Tong Pass, Xiaoguan/Xiao Pass, Wu Pass). The walls and city layout of Chang'an were geared towards city administration (and perhaps grandiose as well as flood mitigation - although Chang'an flood protection was less-than-optimal), rather than defence.

What border cities were most at risk during the Ming period and how were they garrisoned?

DeleteI would also love to see you write something about the siege campaigns Zheng Chenggong conducted in Southern China!

I think Datong city is a good example of a defense-oriented military city (there are others, but Datong is the first city that comes to mind).

DeleteUnlike the oversized Tang Dynasty Chang'an, Datong's area was only 2.6 sq km, and its wall was 7.3 km (entire circumference). The wall was 14 m tall and 12 m thick, and supported by 48 rectangular bastions (12 on each side)and 4 corner bastions, spaced 113 m apart, as well as 96 guard posts (Wo Pu).

As for your other question, I speculate that the wide chemin de ronde on Chinese walls was indeed designed to facilitate troop movement, to allow cavalry, siege engine and supply to be moved up the wall, and to better withstand enemy siege engine. Most Chinese cities were built on flat plain, so siege engine was probably a much more serious issue compared to elsewhere.

At Datong makes much more sense to me, what kind of population did it have during the Ming Dynasty?

DeleteI've read that Datong had a military household population around 290,000 ~ 400,000, and 80,000 ~ 140,000 were in military service. I can't find data on civilian population.

DeleteAlso this refers to the population of entire Datong garrison and not limited to the city itself though.

(Datong Garrison included, among other things, at least seventy-two fortresses, and countless other lesser forts, fortlets and watchtowers, most of them lost to history. Even Datong city wall itself was largely destroyed. The current one is rebuilt in 2008, which caused quite a controversy as the Datong mayor basically "rebuild" the wall that wrap the old ruin inside it.)

I think you mentioned that by the Song Dynasty most walls in big cities had brick coverings. But this paper claimed that wasnt the case until the Ming https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0214119. Thats a big odd considering from what ive read on the subject dont you think?

ReplyDeleteThough I think they mentioned most of their sources do not go past the Ming era and they only had a few records before the Ming.

As far as I can tell, Song period walls became more brick-based in response to the increasing sophistication of siege weaponry, but not so much for Yuan period where even Beijing walls (after it became the capital of Yuan Dynasty) were still only rammed earth.

DeleteHowever, it's possible that the author of that paper has access to more detailed data that I don't have.

The author of the paper claims only 26 cities in the Song were built with brick walls. But they also claim they dont have too many records before the Ming

DeleteIsn't the brick mostly just a thin cladding of rammed earth walls; something to make them more resistant to weathering?

Delete@wakawakwaka

DeleteGiven that I don't have more data than the paper author, I'd go with what he claim. Still even 26 cities is a pretty significant step up from the previous dynasties.

@Simon Stevin

The bricks are pretty massive and durable by themselves so they also add to the durability of the wall.

But the author of the paper claimed that no "major cities" during that time had brick coverings on their walls

Delete@wakawakwaka

DeleteI can only do quick google search for info. As far as I can tell, Dongjing (Northern Song capital) had brick imperial city wall (it had three layer city walls, the imperial city was the innermost one), and Yangzhou, which was a major city, also had bricked walls. Bricked wall became even more commonplace during Southern Song period.

Thats why i felt something was missing about that article i had found

Delete