Individual spacing and formation frontage

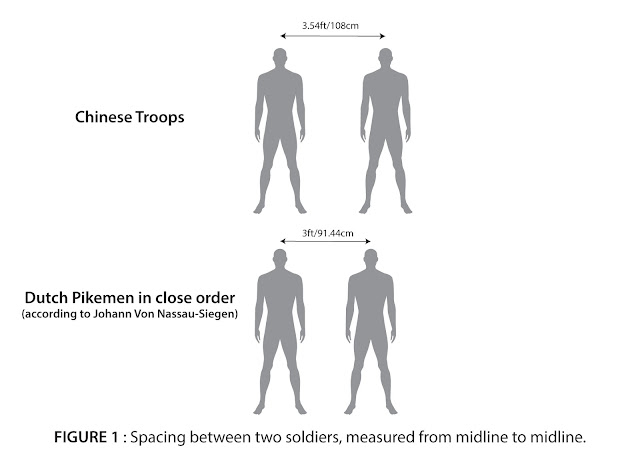

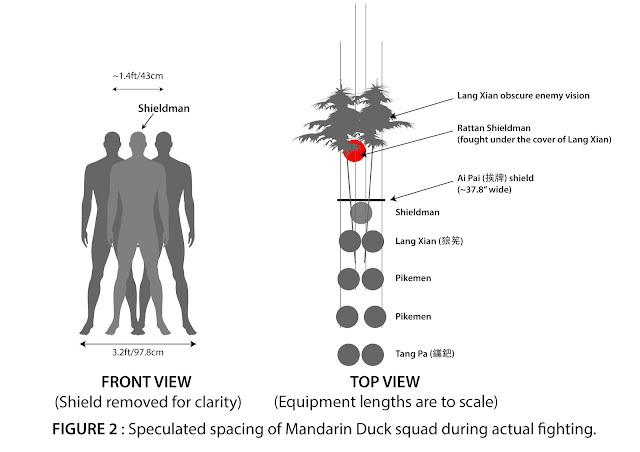

Generally speaking, four typical Chinese soldier would occupy a five chi (approx. 5.35 feet or 1.63 metre) by five chi square. In other word, space between two soldiers, measured from shoulder to shoulder, is roughly 2.1 feet. For example, an early Mandarin Duck squad employed by Qi Ji Guang (戚繼光) would occupy a rectangular space of five chi wide and one zhang five chi long (5.35 feet × 16.05 feet).Ming period military theorists preferred this spacing probably due to the significance of number five in Chinese culture (Five Elements, Five Classics, five appendages, etc.) more than anything else, although it did serve a more practical purpose — five chi was a good spacing for fighting in narrow, maze-like trails, footpaths and paddy field ridges, all common geographical features of South China, as it maintained a fine balance between formation density, manoeuvrability, and situational awareness. A battle in such terrain required an army to be able to quickly disperse into numerous small units and occupy as many trails as possible. At the same time, individual small units must maintain coherence without losing contact with each other, while checking for potential ambush (hence the emphasis on small unit tactics in Ming infantry doctrine). Once the fighting took place, occupied trails could be used for reinforcement, flanking manoeuvre, ambush and counter ambush (whilst preventing the enemy from doing the same).

A densely packed and relatively inflexible formation would find it extremely difficult, if not outright impossible, to manoeuvre such terrain, while a loose skirmishing formation would be quickly overpowered by the combined arms of Mandarin Duck squad.

Modern double file formation and hallway saturation tactic used by special ops can be seen as the contemporary application of similar concept.

|

| Aerial photo of paddy fields during harvest time. Zhejiang, China. |

Other spacing were also used. Xu Guang Qi (徐光啟) for example chose four chi, five chi and six chi spacing for some of his formations.

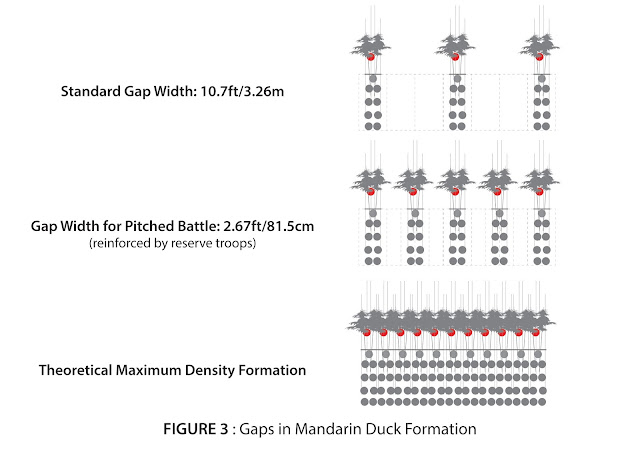

Gaps in the formation

Like ancient Romans, many Chinese armies employed gaps in the formation, albeit on a much smaller scale. Instead of using large gaps equal to the width of entire maniple of legionaries (hundreds of men) like the Romans, Chinese armies utilised small gaps of approximately one zhang wide (approx. 10.5 feet or 3.2 metre) that could only accommodate five to twenty men. Nevertheless, the purpose of maintaining such gaps was essentially the same — to facilitate unit rotation.While Chinese soldiers had faced many different enemies including well-drilled armies, savage hordes and undisciplined mobs, the risk of enemy troops penetrating into the gaps never seems to occur to most Chinese military thinkers. In other words, they never thought of these gaps as potential weak points. It is possible that these gaps were simply too narrow to be exploited, or generally consisted of untraversable terrains such as flooded paddy field patches.

Besides, many Chinese armies often made area denial weapons such as caltrops and cheval de frise standard issue (for example, Qi Ji Guang's army had six cheval de frise and ninety caltrops for every twelve men, in addition to one cloth wall). Presumably, these area denial weapons could be deployed quickly to punish any enemy foolish enough to attempt to penetrate into the gaps.

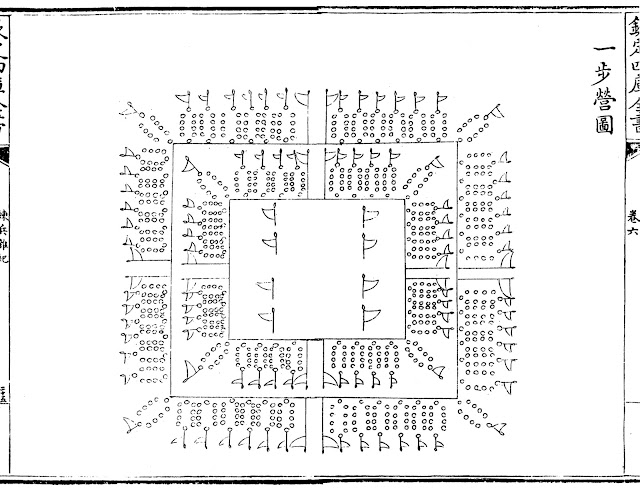

Default to Hollow Square

hollow infantry square (or other squarish formations with no vulnerable flanks or rear, such as a wagon fort) had become essentially their default formation, as infantry square was the most logical and effective formation to defend against cavalry charge and flanking manoeuvre. The practise was especially noticeable in the North, where Chinese faced many nomadic horsemen, but seems to be carried over to the South as well. While Chinese faced mostly foot soldiers in the South, the prevalence of ambush and guerrilla tactics made this formation a necessity. Besides, almost none of the enemies that Chinese faced had the firepower to outshoot them, making the biggest weakness of hollow square formation a non-issue.Chinese armies utilised both large, regiment-sized square as well as multiple smaller squares working in tandem with each other. However, Chinese squares were relatively immobile and generally ill-suited for offensive role (unlike later Napoleonic squares).

Field fortification

|

| Example of a fortified camp, from second edition 'Ji Xiao Xin Shu (《紀效新書》)'. |

Whenever time and resource permit, Chinese armies would construct incredibly fortified military camps known as Cheng Ying (城營, fortress camp) complete with multiple layers of wooden and earthen walls, watchtowers, trenches, ditches, abatisses and punji pits, as well as defensive trebuchets and hundreds of crossbow traps. If building such sophisticated camp was not possible, they would opt for simpler palisade fencing and ditches. For truly simple camps or fortified positions that could be build hastily, Bu Cheng (布城), cheval de frise, caltrops and anti-cavalry trip ropes were used instead.

Interesting post as always. I find the Mandarin Duck formation fascinating, but wonder about how it worked in practice; do we have records of how it performed in action? I assume it was effective against the pirates, but for instance was it used against regular Japanese troops in Korea, and if so how did it fare (I think troops trained in its use were in one of the contingents sent?)

ReplyDeleteGood day Clibinarium =D

DeleteAgainst Wokou pirates, Qi Ji Guang's army achieved victories and kill-ratio that are truly incredible, at time killing thousands without a single casualty in return (these are not boasts or exaggerations, however keep in mind that most casualties happened after one side breaks).

I've since expanded my knowledge on Imjin War (only a little bit though) and can answer you better this time:

For Imjin War, most Chinese troops that went there were Northern cavalry, and Ming army only engaged Japanese troops in open battle two times(Byeokjegwan and Jiksan). Both battles involved a few horsemen against numerous infantry (3~5000 Ming vs 3~40000 Japanese, including reinforcement)and both ended inconclusively. Ming was disadvantaged during Byeokjegwan but gained upper hand during Jiksan.

Other land battles were all sieges.

Several ex-Qi Jiguang contingents did went to Korea, but their only achievement of note was becoming the first to capture Moranbong during Siege of Pyongyang.

Other than that, Wu Wei Zhong (one of the early followers of Qi Jiguang) seems to get ambushed by Katō Kiyomasa once, losing 200~300 men, many of them drowned.

As for Mandarin Duck Formation itself, the more I look at it, the more it looks like a simple "shield in front + pikemen behind" formation. I don't think there's any hidden features that make the formation especially effective/ineffective or anything (aside from the bamboo Lang Xian, that is).

DeleteIn fact, it was such as logical thing to do that most armies in the world must've used the formation in one form or another (i.e. both Hoplites and pikemen had well-armoured first rank)

Something like this.

http://i.imgur.com/DCI7FCe.jpg

http://i.imgur.com/OL4QRLR.jpg

Saxony Duck Formation......just joking.

I don't think the Ming was disadvantaged at Byeokjegwan. Several thousand Ming cavalrymen were ambushed by more than 20,000 japanese infantrymen, and the Ming still managed to get away from it. If anything, this shows the inability of japanese infantrymen to cope with cavalry.

ReplyDeleteMing did well in that battle (or rather, the Japanese performance was...less than stellar, to put it kindly), but a defeat is a defeat.

DeleteIt's true that Japanese army at the time was ill-suited to deal with cavalry, since the terrain of Japan is unsuitable for this type of warfare. Consequently, they lacked competent cavalry, as well as the experience dealing with cavalry.

There's revisionist takes that argue that while the Ming were forced from the field, it was mainly a reconnaissance unit that, first, got pushed out, second, gave as much as it took despite facing overwhelming odds.

DeleteTo an extent, it could be considered a skirmish as it was an ambush where the ambush victims managed to fight their way out.

In my opinion , by the time of Imjin Waeran , the former officers of the Gen Qi commanded far less infantry compared to the Northern based infantry. Many of those were dominated by Northern officers who had no prior exposire to Gen Qi tactics. Plus factors like political affiliation and corruption within Ming govt had disfavoured the former officers of Gen Qi who were by Imjin Waeran

ReplyDeletetimes were already aging and handicapped by their association with Gen Qi who himself retired and died in poverty as a result of political persecution.

I recommeded The Book Imjin Waeran by Samuel Hawley and the translated version of Jingbirok , The Book of Corrections written by Ru Songnyong, translated by Choi Byonghyon. These two books are quite helpful in understanding the Imjin Waeran gave accounts of Ming military in the war.

I also tend to not over embelish the prowess of Ming Military during Imjin Waeran. However, I have to say , the role of former Gen Qi 's officers were really discriminated at that time at the expense of the allied forces of both Ming and Joseon military, sad but true.

However , there were " unwarranted "account which need unbiased study on one of the former Gen Qi's officer named Luo Sangji or Nak Sangji in korean who might contributed some Gen Qi military insights to the Korean side. His name was mentioned in the Muyedobotongji ( The Comprehensive Illustrated Manual of Martial Arts of Korea ). The weird also, when I watched the entire episode of Korean Sageuk drama of Jingbirok, Luo Sangji was portrayed as one of the sympathizer to the Korean side in fighting the Japanese and had helped in training, but this was just a portrayal , which needed to be confirmed in reality.

@Wushangkhan

DeleteMuch of what you wrote is true, since most of the former Qi Jiguang officers were subordinated to someone else from the Northern side (and highest commander of the Ming army was of the North), as well as the discrimination/dispute between North & South Ming army/officers. However many of the Northerners would have at least some knowledge of Qi's tactics due to his influence at the Ji Garrison.

Political atmosphere after the recapture of Pyongyang was to sue for peace with the Japanese. Note that corruption and/or incompetence are not to blame (for the most part), instead this was due to the reality that Ming supply line had already strechted to its limit, plus Ming army was still outnumbered. Thus, Southern officers (such as Wu Wei Zhong) that insisted on continue the fight were seen as overly hardline.

As for Luo Sang Zhi, yes he (and several others) did helped in the retraining of Korean force during interbellum (which resulted in the Samsugun army). He actually suggested the idea to Ryu Seong-ryong himself.

The predecessor of Muyedobotongji -- Muyejebo, is basically a recompilation of the training manuals parts of Qi Jiguang's books. Koreans also wrote commentaries on Qi Ji Guang's work, which contain many valuable insights and clarifications that are lost in translation in the Chinese version.

Very good info and graphs!

ReplyDeleteI think the mandarin duck formation began as a patrol and detachment formation, then it seems Qi made it the standard pike formation with a twist for open field battle when he was stationing in the North.

I believe the gaps were there to allow the matchlock gunners to retreat into the formation and support the main troops with long swords. They could have been used as funnels to breakup enemy's mass and let them be flanked from both sides, then meet the long swords head on. Just my guess.

Also, did he ditch the javelins for the rattan shield men up North? Didn't see it mention in 《練兵雜記》.

I am also under the impression that the hollow square above was not a battle formation but a standard camping arrangement of a modern day regiment size infantry group.

Qi Jiguang actually already had a fairly large open battle formation during his anti-wokou campaign. The pictures are based on his early formation rather than the late version.

DeleteYour guess is correct in the late Mandarin Duck Formation, although it is kind of complicated there, since Mandarin Duck troops usually break up and join the shooting. I will touch upon this tactic in my future blog post.

Yes, he ditched the javelins. Explicitly said so in 練兵實紀.

Napoleonic and Colonial period troops did use the square as battle formation, especially against cavalry charge or against natives that did not have enough firepower to outshoot them - just like the Chinese.

Against an army with equal firepower, a line formation could shoot the square into smithereens.

Is there any details about the measurements, procedures and protocol (similar to song dynasty architecture code) behind the design of these fortress camps? Or how long it takes soldiers to erect them?

ReplyDeleteI will try looking for it, but don't get your hopes up.

DeleteIdk if it's accurate but a lot of these Ming formations remind me a lot of contemporary European pike and shot. Lots of pike to scare off cavalry, countermarching arquebusiers on the flanks to shoot.

ReplyDeleteIt seems that the Ming had a looser formation though, and seemed to get more use from a mix of melee weapons. Meanwhile European formations only kept pikemen to scare off the cavalry, as other melee troops were less useful in a world of abundant arquebuses. Spanish used to have rodeleros (sword and buckler troops), for example, but abandoned them in the early 1500s.

Maybe you get that impression because I made a comparison with Dutch pike spacing. Both Chinese and European infantry used pikes and matchlocks, so there's bound to be some similarities. But IMO there were just as many differences, maybe more.

DeleteQi Jiguang's early Mandarin Duck Formation for example looks more like a "reverse tercio", in that the gunners were at the centre, protected from four sides by melee troops (Mandarin Duck units), at least for its ready & march formation.

So rather than a large square with four smaller sleves at its corners (i.e. the "stereotype" Tercio), the formation looks roughly like a "+" shape.

In combat, the gunners would advance to the front to shoot, then retreat behind both vanguard and rearguard when enemy troops get too close. The left and right wings would split into four sub-units (two flanking wings and two ambusher units). This is for the small combined unit (~200 men).

If you scale that up, the full-sized unit (~800+ men) will look like a big cross made up of four smaller crosses, something like "+‡+" shape, if you get what I mean.