UPDATED NOVEMBER 10, 2022

Ming Armour

|

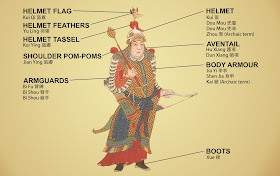

| Components of Ming armour (click to enlarge). |

Armour in the above picture is taken from Ru Bi Tu (《入蹕圖》). This particular suit is a parade armour, although it is reasonably representative of field armours used by Ming troops in North China.

This type of armour is known as Zhao Jia (罩甲, lit. 'Coat armour'), or more precisely Chang Shen Da Jia (長身大甲, lit. 'Long body great armour') for the long version. It is a single-breasted, button up coat reaching below the knees, usually but not always collarless and sleeveless, that comes in many forms ranging from unarmoured riding coat to lamellar, scale, brigandine and even mail armour. For the most part, lamellar and scale version of Chang Shen Da Jia were reserved for elite troops, bodyguards and officers, while ordinary troopers wore brigandines.

Analysis

Chang Shen Da Jia allows for considerable freedom of movement for the arms and neck, and provides good protection to lower legs (especially when its wearer is mounted), both of which make the armour especially suitable for horse archers. Essentially a one-piece long coat, Chang Shen Da Jia also has relatively simple tailoring compared to the complex multi-piece "Cataphract" armour, making it easy to produce and fast to suit up, the latter was especially important for Ming border troops, who often had to respond to unpredictable and sudden nomadic incursions at a moment's notice.While a basic set of Chang Shen Da Jia (plus helmet) already provides adequate protection to its wearer, it still has many vulnerabilities such as unprotected throat and exposed upper limbs to name but a few. As such, Chang Shen Da Jia was often worn together with auxiliary armours such as throat protector and metal plated armguards known as Bi Fu (臂縛) to protect these vulnerable areas. Less commonly, armoured mask, mirror armour, and greaves were also worn with Chang Shen Da Jia.

Qing Armour

|

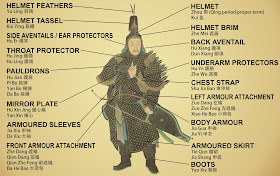

| Components of Qing armour (click to enlarge). |

Two-piece brigandine was already in use since mid-Ming period at the latest and gained significant popularity during the twilight years of the Ming Dynasty, partially supplanting the long coat style. After the demise of Ming, its successor Qing Dynasty inherited the design and pushed for standardisation across the entire empire, eventually leading to two-piece brigandine becoming the dominant form of Chinese armour. Although many alterations, improvements and stylistic changes were applied to the design over the years, the basic form of Qing armour remains largely unchanged from its late Ming predecessor.

Unfortunately, as adoption of more advanced firearms, both by Qing military and its many enemies, quickly became widespread, Qing armour only underwent a relatively short period of development before being rendered obsolete and relegated to ceremonial roles.

It is curious to see the resurgence of multi-piece armour (albeit in brigandine form) during late Ming period. The reason of this shift is unclear, but possibly related to the changing nature of warfare in North China, from dealing with nomadic raids to high intensity struggle of survival between the declining Ming and ascendant Qing. After Qing Dynasty took power, it was able to dominate Mongolia in a way that no previous Chinese dynasties could, so the easy-to-wear long coat armour was no longer needed.

Analysis

|

| Analysis of Qing armour (click to enlarge). |

Other differences between Ming-era Chang Shen Da Jia and Qing brigandine include the addition of throat protector to the armour set (rather than being an auxiliary item), replacement of metal plated armguards with brigandine pauldrons and armoured sleeves/vambraces, as well as the addition of various armour attachments. A notable improvement of Qing armour over its Ming predecessors is the addition of a type of flared cuff known as Ma Ti Xiu (馬蹄袖, lit. 'Horse hoof cuff') to armoured sleeves and vambraces to better protect the hands. Overall, Qing armour offers superior mobility, modularity, and ease of manufacture (as every components of Qing armour, save for the helmet, are of the same brigandine construction) at the expense of reduced protection to buttocks and back thighs as well as longer suit-up time.

Japanese Armour

|

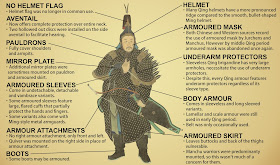

| Components of Japanese armour (click to enlarge). |

Armour in the picture above is taken from tsuki hyakushi (《月百姿》), a nineteenth century ukiyo-e (浮世絵) painting depicting Yamanaka Yukimori (山中幸盛), a prominent samurai that served Amago clan during Sengoku period (戦国時代). This painting is the work of master painter Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (月冈芳年).

By sixteenth century, samurai armour had evolved into its final iteration: tōsei gusoku (当世具足, lit. 'Present age complete armour'), developed as a response to the introduction of Portuguese firearms, shift of battlefield tactics, as well as increasingly intense warfare of Sengoku period. Riveted or stapled laminar armour known as okegawa-dō (桶側胴) also supplanted earlier lamellar armour to reduce cost and improve protection.

Analysis

|

| Analysis of Japanese armour (click to enlarge). |

Samurai of this period were no longer the horse archer-duellists they once were. They became much more close combat-oriented, and this shift of tactic was also reflected on their armour design. Tōsei gusoku protects virtually every part of its wearer's body, and its gaps and weak spots can be further reinforced with auxiliary armour items worn beneath or on top the main harness, befitting a warrior that was expected to engage in high intensity close combat frequently. Some auxiliary under-armours also provide padding and better weight distribution for the main harness.

Another notable feature of later period samurai armour is the shrinking of its spaudlers. Early Japanese ō-sode (大袖) were actually shoulder mounted shields designed to protect the flanks and upper arms from incoming arrows. As samurai became less reliant on archery and more on close combat, sode also shrank in size and evolved into proper spaudlers for better protection and mobility for the arms.

Nevertheless, despite its near-complete coverage tōsei gusoku is not without drawbacks. For an armour with such complete protection, it actually has surprising amount of gaps and flaws that can be exploited with fatal consequences. Many Japanese armours also do not have backing material and are quite noisy to wear due to rubbing between individual armour plates, not to mention this also causes premature wear to lacing, lacquer coating, and the plates themselves.

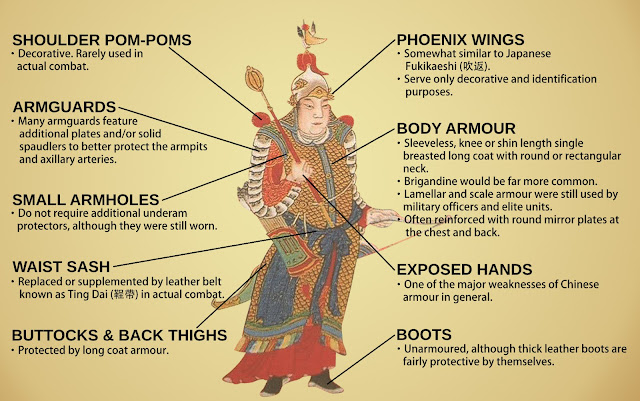

Choice of footwear

The difference between Chinese and Japanese approach to warfare can also be seen on their respective footwear of choice. Ming Northern troops and Manchu warriors alike were predominantly cavalrymen, so their footwear of choice was obviously riding boots (infantry-based Ming Southern troops continued to wear shoes with stockings or puttees, or sometimes straw sandals as well). On the other hand, Japanese warriors were predominantly footmen, with almost no cavalry to speak of, so their footwear of choice was sandals.

|

| A pair of Ming-style boots, made by Hanfu clothing store Chong Hui Han Tang (重回漢唐). |

A boot is known as Xue (靴) or more rarely Yao Xie (靿鞋, lit. 'Shafted shoes') in Chinese language. Traditional Chinese riding boots share many similarities with neighbouring horse cultures such as the Mongols. They can be made of either cloth or leather, although military riding boots are exclusively made of thick, stiff leather to better protect ankle joints. Due to the cold and dry climate of North China, traditional Chinese riding boots are lined with layers thick fabric. Stockings known as Wa (襪) are usually worn underneath the boots.

Unlike Western-style riding boots, traditional Chinese riding boots are flat-heeled. They have unusually wide shafts and comparatively short vamps, which serve the same purpose as heel, (i.e. to prevent the foot from slipping through the stirrup and get stuck). Both Western and traditional Chinese riding boots also have flat and smooth soles for the same aforementioned reason. Still, boots with flat soles are more slippery, which renders them less suitable for foot combat, especially in rough terrain.

Traditional Chinese boots are almost always pitch black in colour contrasted with pale white soles. They generally have less prominent and rounder upturned toes than Mongolian boots (even though upturned toes design seems to originated from China), and many boots do not have upturned toes at all.

|

| A waraji. Note the toes jutting out from the front edge of the sandal. Straw sandals are still used in traditional Japanese stream hiking known as Sawanobori (沢登り). |

Japanese warriors made use of flip-flops and sandals made of rice straw, called zōri (草履) and waraji (草鞋) respectively, although waraji were by far the more common of the two. Japanese sandals provide excellent ventilation (effective in preventing athlete's foot) and ankle mobility, as well as a firm grip on rocky or mossy surface, making them the prefect footwear to use in the mountainous and humid Japan. While straw sandals are less durable than shoes or boots, they can be cheaply replaced and even manufactured on the fly as long as there is raw material available.

During cold seasons, divided toe socks known as tabi (足袋) can be worn together with sandals. Samurai that wanted better protection for their feet may wear armoured kōgake (甲懸) on top of the socks.

Further reading

(Patreon early access) Flaws and gaps of samurai armour

(Patreon early access) Auxiliary armours of Qing brigandine

|

| If you like this blog post, please support my work on Patreon! |

If sleeveless armor is for horse archering

ReplyDeleteThen why joeson brigandine have sleeves

Ps did wing brigandine also sleeveless?

Sleeveless is nice to have for archery, but isn't a strict necessity. It is also a trade off between more freedom of movement vs more protection.

DeleteQing had both sleeveless and sleeved brigandines.

"Due to the flexible nature of Chinese-style brigandine"

ReplyDeletecould you explain this?

Flexible as in not rigid like plate armour?

DeleteBrigandine is relatively more flexible than plate in general

DeleteWhat I want ask is, is chinese brigandine is more flexible than other countries?

and I want know, how flexiblity of armor is related weight distribution

DeleteCan't think of many countries that used brigandine...anyway, if we compare a Chinese brigandine to a European brigandine, it is indeed more flexible/loose-fitting.

DeleteFlexible armour, like mail, basically let your shoulder to support its entire weight (wearing padding and belt helps a lot though). Also if you change your body position (let's say going all-four), the body part that has to support the weight change as well.

DeleteRigid and form-fitting armour such as plate armour can distribute its weight more evenly,thus lessen the burden to the body.

Speaking of Joseon, I really wanted to include them (and Vietnam) in this blog post as well, but my knowledge to Joseon/Vietnam armour is extremely limited, and good period paintings are hard to come by.

DeleteYou guys can forget about Vietnamese armour since there is little to no evidence about it. Even harder when asks a Vietnamese doctorate about their ancestor's armour since they will tell you their ancestor go to war with bare foot and bare naked.

Delete@Aomari2

DeleteGood day and welcome to my blog.

Vietnamese going to war naked isn't wrong, as similar descriptions also show up on Ming records. However that's not the entire picture, since Vietnam wasn't even unified at that time, and Ming had mostly encountered the remnant of Mac Dynasty, sandwitched between Trinh-Nguyen war.

@春秋戰國:

DeleteIf they were like that there is nothing to complain but they weren't. According to historical evidences, the basic equipment of levy class soldiers is clothes and boots beside weapons and shields.

Checked my source. Ming records describe Mac troops as having rattan hat (but did not wear it), untied hair, barefooted, and did not carry anything on their shoulder other than their weapons.

DeleteIndeed no mention of nakedness, only barefoot.

About barefoot. That is acceptable because Vietnamese enjoy walking and running barefoot for hundreds of years. Not because they can't make or buy shoes, they simply liked it. But in war that is a different matter, because all war equipment are supply by the state including shoes.

DeleteWhich state? The troops mentioned in Ming records are Mac troops of the 17th century. By that time Mac was nothing more than a shadow of its former glory.

Delete@春秋戰國: Trinh and Nguyen lords, of course.

DeleteThe Vietnamese military didn't only use levies as troops no? Did they not have professional soldiers? And from what I've seen from statues in Vietnam, it seems that they depict famous generals wearing armor that seems similar if not identical to Chinese armor from various periods.

Delete@Unknown

DeleteVietnamese most certainly had some form of professional military and/or royal guards. Also given that they are at close proximity with China, heavy Chinese influences are to be expected (although they are quite different also).

Vietnam is also an international hub of sort, so influences from Japanese, Europeans and SE Asians (i.e. Siam etc) are also very evident on their weaponry.

@春秋戰國

DeleteLater Ly to Ho dynasty Era: Fubing system from Tang dynasty.

Later Le to Early Tay Son Era: Ming dynasty military system with modifications.

Taken from "Lịch triều hiến chương loại chí" (歷朝憲章類誌 lit. Various dynasty encyclopedia).

Since the Zhao Jia is commonly worn by northern soldiers who are usually mounted, what kind of armor(s) would southern infantry wear?

ReplyDeleteZhao Jia as well, usually (but not always) only waist or thigh length.

Deletehttp://blogfiles.naver.net/20150329_124/53traian_1427563969981mv11C_JPEG/mongol_japan.jpg

ReplyDeleteIs this a mongol armor or qing armor?

some data claim this is a mongol armor

Unmistakably Qing, probably late Qing even. Japanese mislabeled the armour.

DeleteIf the size (especially the siyah) is any indication, the bow on the side is probably a Qing bow, or Qing-influenced Mongol bow.

Have I understood correctly that the 罩甲, Zhao Jia, is a description of form, i.e. long skirted/sleeveless/collarless? But it could be of various material, e.g. scale, brigandine, mountain pattern etc.

ReplyDeleteYes, and it is not necessary long skirted and not necessary even armoured.

DeleteDid the Chinese ever developed equivalent of elbow and kneepads? I would assume it's difficult to armor these joints and still maintain mobility.

ReplyDeleteNo AFAIK. They usually just extend the armour skirt to cover the knees.

DeleteThe manica-like armguard does protect the elbow.

I've seen knee pads on a Song period warrior sculpture from southwest China. So I think knee pads did exist, but they were probably not commonly used or limited to certain regions.

DeleteDo you have a picture of it?

DeleteVery comprehensive analysis.

ReplyDeleteJust a note though, it seems the samurai of the period had leather shoes or boots for riding, but they might not be considered part of the set of the Gusoku.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SsqsL15C4OA

I am aware of it. Samurai did ride horse sometimes after all so they got to have some riding equipment top. It just isn't as common as the waraji.

DeleteDo you have a picture of inside of chinese brigandine?

ReplyDeleteThis is an example of a Qing brigandine for the rank and file, with iron plates only cover the bare necessity of body.

Deletehttp://i.imgur.com/XQXlWKv.jpg

do you think ming brigandine use simillar size of plate as this one?

Deleteand do you know how many rivets were use to hold each plate and their locations

@s ss

DeleteProbably similar, although not many Ming brigandine survived so I can't be sure.

For rivets, depending on the location, two to four rivets. Body plates have three, for example.

The illustration of samurai armour, though done during Edo era is actually the classic O-yoroi type during the Heian era. The boxy cuirasse with a lot of colourful lacing, large shoulder guards are indicators of the old style. Sengoku and subsequent Edo era armour are tighter fitting lamellar with less lacing and sometimes riveted like European armour. Some also use Portuguese style full plate cuirasse.

ReplyDeleteI identify the armour as a more contemporary version mainly due to its seven kusazuri instead of the usual four, found on O-yoroi armour. Its Do also strikes me as quite curved.

DeleteThe sode are indeed larger than most sengoku period armour, which I think is also an attempt to reincorporate O-yoroi elements into Edo period armour.

Agree, it's the Edo equivalent of O-yoroi. It is interesting because it was deemed as cumbersome and impractical during the Sengoku period. Worn mostly by Daimyo who want to show their ancient lineage. Curiously, it did retain the style where the right arm has no sleeve guard to make drawing the bow easier (a characteristic of Heian era horse archers). But as you said, using sandals is more for foot combat. The actual Heian armour set includes some form of furry shoes / boots.

Deletehttp://www.yurukaze.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/O-yoroi-the-early-Japanese-armor-of-samurai-class-of-feudal-Japan-02.jpg

Updated my blog post slightly to include the sode change.

DeleteKote was originally archery sleeve that protect the left arm from being hit by bowstring (from botched shooting), that's why only the left arm has it originally.

As there were no wars during the Edo period, the Japanese greatly romanticised the samurai image and had gone back to the classical style.

ReplyDeleteany protection between ming long coat armor?

ReplyDeleteWhat do you mean by "between" ?

DeleteMiddle

ReplyDeleteIf you mean what is worn beneath the armour, most likely only normal clothing.

Deleteso middle spot is compeletly vulunerable right?

DeleteI still don't really get yoir question, but if you mean lower midriff (that body part not protected by Samurai armour), Ming long coat armour doesn't have this problem.

DeleteWhat I mean

DeleteIf Ming long coat armor is not overlapped would'nt that make middle of torso compeletly vulnerable?

No? Although the plates didn't overlap there isn't any gap either.

DeleteI know ow the use of chainmail armor is somewhat limited or even rare in East Asia compared to other parts of the world, but would it be known that a shirt of mail would be used in conjunction with these armors? I'm curious if this was historical since I am planning in the future to assemble my own suit of late Ming and early Qing styled brigandine armor.

ReplyDelete@Unknown

DeleteAll I can say is "possible".

On one hand, mail armour was worn under other armour since Tang period (we got a mural from Dunhuang to prove it), although it was evidently quite rare. In the rare case that someone was described as wearing multiple layers of armour (i.e. 兀顏光 from Water Margin), he was often described as something extraordinary.

On the other hand, many Qing painting depicts officers wearing mail shirt alone.

I see. I know that Japanese mail used both techniques, but do you know if Chinese mail was riveted and or butted?

DeleteChinese mail is 4-in-1 Riveted.

DeleteThanks for the info! I'll keep watching this blog as there's not a great deal of sites that go in depth with Chinese arms and armor like yours. And whenever this suit will come together, hopefully sometime next year, I'd like to share it to get your input!

DeleteI will be looking forward to that.

DeleteMing brigandine pic

ReplyDeletehttp://imageshack.com/a/img924/8953/XN0QTU.jpg

Yes, I am aware of it, although I personally think that it is from early Qing (or Southern Ming contemporary to early Qing Dynasty).

DeleteMr chen

Deletewhere do you get this picture?

https://2.bp.blogspot.com/-vjrZnRNfzMk/VwS1ylgyzXI/AAAAAAAACoU/ERw7GACzSnkGj5KjrxpPpBeIg1pl7jVVQ/s640/songzmd.jpg

https://2.bp.blogspot.com/-cSwntu_ux1g/VhWmOyi6-7I/AAAAAAAABGw/C-MSlGqNWjQ/s640/412.jpg

ReplyDeleteI've never seen this kind of 2-piece armor

especialy that skirt armor. Do you know anything about this?

From 《王瓊事蹟圖冊》,a set of scrolls depicting Wang Qiong's(1459-1532) achievements.

DeleteIn this particular scroll Wang Qiong is the Military Commissioner of the 3 passes(Taiyuan border garrison).

The individuals with waist length brigandine and brigandine tassets is presumably some sort of ensign/messenger.

@Wansui

DeleteGood day, it's been some time.

To this date I am still not sure what to make of these "brigandine tassets". It is similar, yet also very different from Qing period "apron". I also remember there's one mural in Fire God Temple that depicts similar tassets, but on traditional Chinese armour.

Great post, is there any reason why there is a significant difference between the Ming and the Qing armour, and what is the difference between Chinese armour and Mongolian armour?

ReplyDeleteThe change from one piece to two piece armour actually happened before the fall of Ming Dynasty. Qing simply inherited the latest armour style from Ming.

DeleteMongolian armours are (for the most part) direct copies of armours used by the cultures they fought with/conquered. So Mongols in China used mostly Chinese-style lamellar armour, while Mongols in Middle East used Middle Eastern-style armours, etc.

I was looking for references for Chinese arms & armors and I've found your blog, which is amazing and I wanted to thank you for the articles,they are great!

ReplyDeleteI also wanted to comment under this section because I am interested in Japanese arms & armors and I've been able in the past years to get proper and solid knowledge, and I have to say that your brief analysis and introduction on Tosei Gusoku is one of the best I've read in a non Japanese-themed blog (And I have to say that is even better than some Japanese-themed sources).

If I might add something, I'll stress the fact that Tosei Gusoku in Japan were developed when the armorers switched from a lamellar construction to a solid plate and lames ones, to save time and money for the new demand of armors, in the mid-late 15th century.

Also, armpit were protected by armor pieces like the Wakibiki, or the Manju no wa which was similar to european arming jacket and voiders.

And the mid riff as you pointed out, in some armor was left unprotected, only covered with a thick obi. But some times there were hidden mail/brigandine section under the lacing or over it in the form of patches; sometimes the lacing was entirely replaced by mail/brigandine section, or made entirely with plates which leave no gap.

On high end examples the breastplate, the sode, the suneate and even the shikoro to some extent were lined and covered by leather and or ieiji.

Cavalry unit were deployed in some cases in Japan, especially in the Kanto region, so the warrior there used boots rather than straw sandals.

The only thing I would change in this article is the picture you have used, Kuniyoshi is a great artist but his style is kinda "anachronistic".

I would have used this picture:

"Samurai with Iron Mask" by Kiyochika Kobayashi

https://www.artelino.com/auctionimages/items/21338g1.jpg

I'll hope you might find my comment interesting, and again nice job with all the content.

Luca

Good day Luca and welcome to my blog! Glad you like my article. Your comment remind me of that one (large metal lames), I should update my blog post at some later time.

DeleteAs for armpit armour, I actually point that out in the picture (you can click on it if the text is too small to read). I only mention some auxiliary armour pieces because it is hard to go through every single one of them in a brief introduction article.

The fur boot have been pointed out to me in one of the previous comments so I am aware of it (and samurai cavalry). That being said, this is a comparison between the "standard loadout" of three relatively well-off warriors, so I omitted less common equipment in the comparison.

I pick the Kuniyoshi artwork because it is the only one I found with a samurai standing in complete loadout while facing a similar direction as the other two Chinese warriors. Your picture is in many way better than what I found, although the sode is sadly missing.

Rule number one: read twice.

DeleteI've noticed just now that the wakibiki were indeed mentioned in the picture, sorry, my fault.

I think your choice of artwork is a good one. Although is an ukiyo e, the picture is looking good in the comparison with the Qing and the Ming soldier.

In the artwork of Kobayashi a late and mature tosei gusoku is depicted, by that time at the beginning of the Edo period, Sode were seldom worn, they were directly integrated in the kote (bishamon kote style) or abandoned in favor of small shoulder guards called kohire.

If you are interested there is a similar picture with less armor, where the samurai is looking in the same direction of the two Chinese warriors, but this time waraji are missing which might be a problem as well.

If this might be useful, I'll leave It here.

The artwork is "Yamanaka Yukimori" by "Tsukiyoka Yoshitoshi"

http://blog-imgs-72.fc2.com/p/i/g/piglet01/20141211223024d91.jpg

P.s

I think there is a lot of potential in this blog and in your work, I'll probably have future questions since you seems to be quite knowledgeable; hope this won't be annoying, feel free to answer when you'll have time!

Have a nice day, Luca

@Luca

DeleteAdd a line in the article that mentions the okegawa-do stuff.

I wish I find your second picture earlier, that's certainly a better one! The accuracy of the armour certainly far outweight the missing waraji (and Horo, but that piece is not very common as well so I won't miss it)! I will probably find a time to update it into the blog post.

I am also trying to find a good Joseon Korean warrior painting to no avail. Then again, as Joseon Dynasty survived well into 19th century, I do not known which period is appropriate.

While I'm quite confident with my resources on Japanese armor inside art, I don't think I could help at all with Joseon artwork.

DeleteOn a side note, I know that it was fairly fashionable for samurai warriors of the Azuchi Momoyama period using Chinese elements on their helmets, both for decorative and defensive purpose. For example, Chinese and Korean helmet bowls were used. Do you know if cuirass or other armor element did reach Japan?

Also, do you know if it was true the reverse situation? Did Mainland people used Japanese armor elements?

I also vaguely remember Oda Nobunaga putting on a Ming coin as his banner.

DeleteCan't speak for the Korean either. For the Chinese, Japanese influence is more evident on their weapon rather than armour (sword, Changdao, arquebus). However, this armour...specifically the neck armour on the mask, seems very Japan-like.

http://greatmingmilitary.blogspot.com/2015/02/plate-armour-of-ming-dynasty.html

This is definetely something I would love to further research and investigate, both for armors and weapons.

DeleteAt least to me, It seems quite unlikely that there was any influences in the 16th century, especially for Japan since the foundation of their early armor was Chinese.

That throat guard is quite similar to a Japanese yodare kake indeed.

By the way, is there any survivals/ reference other than manuals depictions of the 龍鱗甲 and 鞋底甲?

Because I Think that gyorin zane armour in Japan might came from these Styles.

I'm no expert on Japanese armors, but based on my vague knowledge, I would say that Japanese armors are most similar to the Chinese armors during the Age of Fragmentation, around 3rd to 6th centuries AD. After that they sort of diverged onto their own paths, with Chinese armors being influenced by Central Asian armors, while Japanese armors developed their own unique styles. I definitely wouldn't call 16th century Japanese armors as mere copies of Chinese armors.

Delete@TheXanian

DeleteSure, it would be a on over semplification.

Early Japanese armor was probably Chinese in design, or Korean.

I have been really interested in the topic of Japanese armor and I came here to see if there were some sources saying that the Chinese used Japanese armors or viceversa, influences included.

During the late 16th century, in Japan armor became a status symbol and a way to be recognizable in the midst of the battles, so some warriors started to use weird and fancy helmets, incorporating both Chinese and European features.

It would be interesting to see if something else comes up!

@Luca Nic

DeleteUnfortunately, there's no other reference on those armours.....Well, there's one surviving brass scale armour, possibly late Qing, that is somewhat similar to 渾金甲, although that one has no helmet, sleeves,and boots.

There's some discussion among Ming officials, I forget which period, to import Japanese armours, but that plan did not come to fruitition. Some Japanese (captured during Wokou campaign or Imjin War) also served in Korean and Ming army.

Koxinga certainly had access to Japanese armour, but only in limited number.

Scale armour are actually very rare in China, lamellar (later brigandine) being the norm.

I wonder how a typical southern Chinese warrior compared to the three warriors listed here. It seems that the southern Chinese had some rather unique styles of armors made out of rattan, paper, and leather. And it also seems that the southern Chinese retained the Song style lamellar armor for much longer. I heard that there was a set of Ming iron lamellar armor unearthed in Guangzhou, and after reconstruction it looked very similar to the Song armors depicted on the military manual Wujing Zongyao.

ReplyDelete@TheXanian

DeleteThe Southerners used a different style of helmet. They typically did not use armguards, has different footwears (shoes or waraji-like sandals) and used shorter (waist length to knee length) armour, but otherwise still the same old Zhao Jia.

Rattan was actually rarely used for armour except for helmet and shield.

The notion that traditional-style lamellar was used in South China for much longer is a speculation, albeit probably accurate. There's is a Qing period painting by two Japanese eyewithnesses that shows some Chinese troops still use traditional armours in the 19th century.

There seems to be some issues with the reconstruction of that Guangzhou lamellar, but it shouldn't be too far off...I hope.

If I remember correctly, there were at least two types of rattan armors being mentioned in Ming military manuals. The first one was a waist-length armor made out of rattan canes in a woven manner, kind of like a rattan version of the mail armor. It has to be soaked in tung oil and then dried, and this process needs to be repeated several times. The second one is a type of lamellar armor made of small rattan plates, and it is said to be used by the marines.

Delete@The Xanian

DeleteTrue, and both rattan armours can be found in my other blog posts. But they were rarely used.

NOTE: I updated the blog post with a more historically accurate painting of the samurai, along with some minor editing on the article. For those interested in the old picture, you can find it here:

ReplyDeletehttps://4.bp.blogspot.com/-V28yYqnGmeA/V7EYMKnYrTI/AAAAAAAAC_o/tKe4sN9Af-AvFfeexNFPt5Po7R7M_I20QCLcB/s1600/Ming_Qing_Japan_Warrior.jpg

Hello, do you have any information about early Qing/Later Jin armour, especially the face mask? I've seen people on Historum say they used lamellar armour, Osprey also says that.

ReplyDeleteWhat are your thoughts on this?

The existence of Jurchen/Manchu lamellar armour and face mask are attested in written records, but none of them survived I'm afraid.

DeleteWould it be a stretch to say that they still used the Iron Pagoda style of armour?

DeleteWhile certainly possible, we don't have any evidence that suggest for or against it.

DeleteI heard the written records mention barding as well, is that true?

DeleteAnd would they be lamellar as well?

ReplyDeleteYes and yes (lamellar & barding). We know for certain that they used lamellar, whether they were the old "Iron Pagoda" style or the "Great Coat" style we have no idea though.

DeleteAs a side note, both Ming and Mongols likewise had barding and lamellar.

Do you have the specific sources for lamellar, barding and face mask available?

DeleteWhat specific that you need? Do you mean records of Ming/Jurchen/Mongol barding?

DeleteYes and the Manchu lamellar as well.

DeleteMentions of Manchu lamellar and barding can be found in both Ming and Joseon written records. For Mongols, there is a record about cavalry under Altan Khan with Ming style armor including brigandine and lamellar, and his elite troops had barding.

DeleteFor Ming barding, there are some records of bardings being taken out for maintenance, as well as at least one late Ming woodblock print depiction.

Thank you very much!

DeleteI forgot to add the face mask.

ReplyDeleteFor Ming mask I only recall one record of Shenji Batallion equipped with mask, as well as Tieren. Mentions of Jurchen/Manchu mask can be found in Ming, Joseon, and Western witness records.

DeleteThis has been extremely useful and informative, thank you!

Deletedo we have any surviving examples or any hint to guess how they are looked like

DeleteThere's a recently auctioned brigandine peytral that possibly dated to late Ming period.

Deletecan i see the picture?

Deleteand do we have mask as well ?

No mask. This is what the peytral looks like:

Deletehttps://i.imgur.com/dwsYxVQ.jpg

its remind me a qing skirt armor

Deletevery im suprised

p.s fo you have any plan to write article about late ming iron cavarly?

What/Which late Ming iron cavalry? That name kinda lose its significance since any half-competent cavalry unit could be called that.

Delete關寧鐵騎

DeleteThat one is a hot mess of confusing information and conflicting opinions, so I'm afraid it is beyond my ability to give it a good article.

Deletehttps://m.youtube.com/watch?v=rkIZZhbAOwk&t=1032s

ReplyDeletehey matt easton use your image

did he ask your permission?

LMAO, I am surprised myself.

DeleteHi, i've recently been looking at the two versions of the famed 清明上河图 and noticed some ming period military activcties in the painting. Are the paintings an accurate representation of a regular city garrison of the ming period?

ReplyDeletepicture i cropped from the paintings : https://leehungchang.tumblr.com/post/186116736484/soldiers-in-the-two-versions-of-qingmingshanghetu

I have not notice anything out of the ordinary, so I guess they are accurate. Do you have the full hi-ress picture of the painting?

Deletethe wiki article contains the somewhat high res version https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Along_the_River_During_the_Qingming_Festival

DeleteThis is low quality but I think this might be a depiction of early Qing barding. https://scontent.fuln1-2.fna.fbcdn.net/v/t1.0-9/13315473_1167599573279977_4598065487148418861_n.jpg?_nc_cat=100&_nc_oc=AQlyge7aH9uO6pbJr5_ufLjqnaOhjNCIEbT4DjjhT4paoq_JP91aCtMN_OwFe_LzZ5U&_nc_ht=scontent.fuln1-2.fna&oh=871c8c6e4fbc8af3182cc1fbcd82ad7c&oe=5DB2E28E

ReplyDeleteThank you.

DeleteUpdate: This is the 元人秋猎图, a depiction of the Yuan dynasty, but the clothing and equipment are early Qing.

DeleteDid chinese ever used plated mail?

ReplyDeleteIf they did what did they called it?

No, they also didn't have a specific name for it.

DeleteHi again! Had a question about Ming/Qing/Chinese armors I was wondering about:

ReplyDeleteDid Chinese armorers ever make armor (or at least parts like the helmet or mirror plate) that was bulletproof like was done on occasion in Europe and Japan? Seems strange that the Ming/Qing who used gunpowder weaponry extensively would not attempt to make their armors proof against it... (same strangeness goes for other cultures like the Ottomans and Mughals who seemed to have adopted guns heavily yet favored mail + mirror plate for their armors even though that armor seems to be poor protection against bullets...)

As far as I can remember, Xu Guangqi discussed something like that.

DeleteAlso, Quan Tie Jia is said to be bulletproof.

Didn't Manchu and Tie Ren armor are bullet resistant as well?

DeleteAnd the Japanese said that Ming shield and armor are bullet resistant as well.

Manchu armour was discussed by Xu Guangqi.

DeleteTie Ren armour was not described as bullet resistant.

Paper armors(紙甲) were able to stop bullets according to Ming dynasty records "武備要略". Ming and Qing dynasties did develop some types of bullet-rsistent armors but they're usually multi-layers combined with different materials including metals, leathers, cottons and papers. During Battle of Sarhu, the armors wore by Manchus were able to resist bullets shot from both Ming and Choseon musketeers.

Delete@Blogger01

DeleteThere are some evidence that suggest the bullet resistant qualities of thickly layered cotton and paper, as well as one (homemade) test that I am aware of.

About the article,

ReplyDelete"this type of armour has poor weight distribution compared to rigid lamellar or plate armour"

I think poor distribution of weight happen when the armor is an untailored like Medieval mail tunic. If an armor is fastened at the front/back than the armor should hug the body meaning the weight are distributed throughout the length of the torso rather than just shoulder and the waist.

"all of these add-ons were already present on Ming armour"

Is there other showing of this, other than a late Ming brigandine pieces?

"somehow leaves the lower part of midriff (i.e. area between cuirass and tassets) completely unprotected."

Only true for late 16th century armor. Early 16th century at the same time as the Ming armor did not have this gap and in late 16th century there are a number of choices to cover this gap with either mail belt or articulated lower extension of the Do.

"Many Japanese armours also do not have backing material"

The plates are lacquered and there are Japanese armor with backing material. Chinese brigandine also didn't had backing material that prevent metal to clothing contact.

@Joshua

Delete· Ming/Qing brigandines were seldom fastened with chest straps like earlier lamellar though.

· There are late Ming written records mentioning these add-ons in the context of brigandine parts.

· While it's true that you can use auxiliary pieces to cover the gap, it still constitutes a weakness that you have to take extra step to mitigate.

· The problem with backing (or lack thereoff) is more about metal on metal contact than metal on clothing contact.

· Ming/Qing brigandines were seldom fastened with chest straps like earlier lamellar though.

DeleteDo you mean a chest sash like the Varangian bra?

Didn't a flexible armor wrap itself around the body when fastened at the front?

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/22011

· There are late Ming written records mentioning these add-ons in the context of brigandine parts.

Thank you. Do you know where I can read them?

· While it's true that you can use auxiliary pieces to cover the gap, it still constitutes a weakness that you have to take extra step to mitigate.

That's the thing I did not understand about Japanese armor.

This is a Do from around the period of the depicted Ming soldier.

https://collections.royalarmouries.org/object/rac-object-12242.html

The Kusazuri overlap the torso armor leaving no gap. So far all 15th-early 16th century armor I see is like this.

· The problem with backing (or lack thereoff) is more about metal on metal contact than metal on clothing contact.

Didn't most metal armor in the world had metal to metal contact somewhere in their construction?

European, Indian, Chinese armor are composed of metal contacting other metals.

@Joshua

DeleteYes, I mean something like Varangian bra, or at least the strap used to hold mirror plate in place. Flexible armour like mail will sag when you move around so it's better to secure it.

Unfortunately, even I do not have the complete version of the source (I only acquired screenshots of the relevant part).

"So far all 15th-early 16th century armor I see is like this."

Here's one from the 16th century with gap.

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/27582

I don't understand the reasoning for the gap either.

"Didn't most metal armor in the world had metal to metal contact somewhere in their construction?"

Yes, it is inevitable. But still better to reduce it as much as possible.

"Tie Ren armour was not described as bullet resistant."

ReplyDeleteIs it based on the meaning of "sijdegeweer" being sidearms?

From what I found, all meaning of geweer refer to firearms.

Also all translation of of Fredercik Coyett that I read also said that the Tie Ren armor resist Dutch bullet.

"Rifle" is a mistranslation. For source written in the 17th century, we should go with the old meaning.

Deletehttps://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/zijdgeweer

https://www.dbnl.org/tekst/land016mili01_01/land016mili01_01_0027.php (you can try google translate this)

Thank you. I did not notice that zijdgeweer are a word and not a compound.

Delete"Yes, I mean something like Varangian bra, or at least the strap used to hold mirror plate in place. Flexible armour like mail will sag when you move around so it's better to secure it."

ReplyDeleteYes, mail and other flexible armor will sag, but European mail are rarely fastened at the front/back/side.

Such mail armor is like a T-shirt that cannot stretch, there is no way it could rest on the body, otherwise it will not pass the shoulder when worn.

Mail and other flexibe armor made in the style of Do-maru/Haramaki/or fastened at the sides is different story, in my opinion, because with such fastening method you force it to conform to body shape.

"Here's one from the 16th century with gap."

That's why I specifiy 15th-early 16th century.

That armor is quite strange and should be antiquated in the 16th century. It does not have the silhouette of thinner waist so it follow the shape 13th century armor, while the gaps are not present in earlier armor of this type, so maybe it is an imitation combined with late 16th century preference for gap.

From my discussion with Gunsen, I think we could get a pattern of 15th century.

This is old armor before the rigid self supporting 15th century lamellar. As you can see the side sag on its own.

https://i.pinimg.com/originals/e0/fe/90/e0fe90b594143f7d25dc89962c05be09.jpg

This is 15th century lamellar. The waist part is thinner, so it had the benefit of rigid cuirass as well.

https://webarchives.tnm.jp/imgsearch/show/E0017343

These two are from 1500-1570. The form remain the same, but replaced with laminar and also had the lacing reduced.

https://netz-saitama.xsrv.jp/gururi/images/201905_01/p07.jpg

https://pbs.twimg.com/media/EPRiHTqUYAA8vkh.jpg

This is late 16th century armor shape, in this case, the armor is lamellar (or false lamellar). As you can see, it has gaps in the midriff, while previous armor did not.

https://i.pinimg.com/originals/d4/b4/0d/d4b40dfdb346ce84abfc1dc890400f08.jpg

Now I don't know if such development is standard or not. For example this is a 15th century untailored armor (or maybe it is tailored for a person with wide torso) with no gap.

https://image.tnm.jp/image/1024/C0042556.jpg

while this one is extremely narrow at the waist.

https://i.pinimg.com/736x/3e/eb/3b/3eeb3b82c1b4f6fa2cf7dc3e2dc435b7.jpg

The thing is that such gap are purposefully designed, while previous armor didn't had those gaps. One example of that I suspect is purposefully separated is probably the old Kote design being separated into the new Kote and Manchira.

@Joshua

DeleteNow that I've finally getting my latest blog post cleared, I can reply to the comment (I hope I don't forget to reply to something...)

"European mail are rarely fastened at the front/back/side".

Indeed true, and the weight distribution will most likely be affected.

Chest straps and Varangian bras were nice things to have, but not absolutely crucial. The practice wasn't universal in both Byzantine Empire and China (and elsewhere) either.

I must admit I only have some basic knowledge with the development of Japanese armour/weapon, so this is just a blind guess:

Could the gap be a result of cost-saving and cutting corners? Sengoku warfare evolved and increased in intensity quite a lot over the century, so maybe the gap was the result of trying to churn out more armours in shorter period of time?

"Indeed true, and the weight distribution will most likely be affected."

ReplyDeleteSome middle Eastern mail and most East Asian armor are fastened at the front/back/side that means their weight distribution are different to European mail armor and more similar to 14th-15th century Coat of Plates/Brigandine.

"Could the gap be a result of cost-saving and cutting corners? Sengoku warfare evolved and increased in intensity quite a lot over the century, so maybe the gap was the result of trying to churn out more armours in shorter period of time?"

That is what I thought too, the Japanese concentrate on thickening the cuirass and helmet, while reducing as much weight as possible on the rest. I don't think the drive for overall heavier armor exist in China or Japan, as it does in Europe. I remember seeing a 17th century 3/4 Cuirassier armor with a weight of 42 kg.

With the exception of the more solid torso part of the Do and the Kote, the rest of the Japanese armor of late 16th century are more open, lighter and sometimes plain inferior or less sophisticated in construction.

I don't know precisely when the transition start from 15th/early 16th century style to gunpowder armor late 16th century. The earlier armor would be more ideal for a battlefield with minimal gunpowder and more arrows/spear as it is more enclosed.

Here are the component of earlier armor that you can compare to the Japanese armor picture you have.

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/65122

This is how a 1400 Samurai look like.

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/65122

The early 16th century Samurai probably wear the same limb armor, but with better torso armor in the form of laminar and early Okegawa Do.

https://pbs.twimg.com/media/DMv71FDUEAYLPtp.jpg

He wear Hodo Haidate that enclose the back of the leg as well.

https://i.imgur.com/Z4ekaI8.jpg

The Kote is old design, so it goes under the Do. The arm defense are solid or hinged plates with gaps covered with mail or plate. This is a 1400-1450 Kote with European style mail covering the gaps.

https://1.bp.blogspot.com/-jEX0YXVxDeU/XcntCmysdbI/AAAAAAAABnQ/EywBKyeHpycUYTEPGXl56j7DXT56UCmdwCLcBGAsYHQ/s1600/f0b0a55c26f6a76c16c330a770c35858.jpg

The one in the painting had mail on the part under the Do and it also had small plates to cover to supplement the mail.

A real example from Edo Period of old style Kote with mail under the Do and in the armpit:

https://i.pinimg.com/originals/ec/4c/11/ec4c1136f03ab8ce18a066a3258250e0.jpg

The greave is more solid with rigid knee guard and it also cover the front and back of the shin.

https://pbs.twimg.com/media/DEn6gJFUwAA8t96?format=jpg&name=large

As far as I know that is the difference, much of it is based on simple observation and as far as I know probably wouldn't be in a book.

However, while late 16th century "standard" Japanese armor is more open, they did not forget how to create more enclosing armor and the additional armor had a lot more variety than 15th-early 16th century armor.

So an ideal late 16th century with all additional armor would still be better.

According to some researches I've found, Ming-Qing styles traditional Chinese military boots(軍靴、軍用靿鞋) sometime were armored with metal plates or chainmail but they're installed inside(or between) the fabric of boots(鐵甲靴、鐵網靴) like usual brigandine armors, so it's not necessarily unarmored, just not visible from outside.

ReplyDeletehttps://www.zhihu.com/question/339491553

Also as I understand, the regular Chinese foot soldiers usually just wear traditional Chinese linen-cotton flat shoes(中式布鞋) or straw shoes(草鞋)similar to Japanese, only officers, cavalries and elite soldiers can wear boots, there were strict regulations about what kinds of shoes they should wear.

Outstanding article btw!

Good day and welcome to my blog.

DeleteThe "brigandine boots" is extrapolated from a pair of surviving armoured boots currently in the possession of The National Museum of Mongolia. The boots are closer to Chinese style than Mongol style, and given the time period, they were likely issued to a Mongolian soldier serving in the Qing military.

Still, since they are the only surviving evidence, we don't know how common armoured boots were in the past. I put a "some boots may be armoured" note in the Qing brigandine analysis picture to reflect this.

I know of the plates in the boots but not boots with mail where is that example coming from?

Delete@Blogger01

Delete@Tobi

So far I've yet to find any evidence of Chinese armoured boots lined with mail. "jazerant" vambraces were quite common during Qing period though.

is it possible that the armor in chujing rubi tu are made by fabrics with armor patterns printed on it? it seems illogical to wear actual armor and walk a long distance

ReplyDeleteNo? The guards were probably in parade gear, but they were still in the presence of the Emperor, with all the potential risks that entail. Also, there are various surviving records of manufacturing/storing of metal armours (including the more ornate ones) used by Imperial guards, but this so-called "painted-on armour" never existed in Ming records as far as I am aware.

DeleteIt seems even more illogical to me to NOT wear actual armour during a parade. Various cultures, both East and West, both past and present, parade in actual armour all the time.

Scott Rodell had introduced some antique Qing dynasty military boots with metal sole(鞋底甲), very interesting.

ReplyDeletehttps://youtu.be/Su2GIVzxakc

Interesting.

DeleteI don't think they are called 鞋底甲 historically though?

Did not realize you updated the article!

ReplyDeleteWould you be inclined to do a comparison for Korean and Vietnamnese armor with enough sources supplied?

ReplyDeleteNot any time soon unfortunately. I am pretty occupied at the moment.

DeleteHi, love your blog and now the patreon!

ReplyDeleteOne thing that confuses me doing some research is, does the Qing armor essentially look like the Ming armor during late ming period (When they are fighting each other), ie already influenced by Ming culture?

I'm very very new to 1600's warfare but it's been interesting so far :-)

Welcome and thanks for supporting me!

DeleteYes, Later Jin/Early Qing armours look pretty similar, in fact nearly identical, to late Ming armours. Ming Dynasty ruled the region we now call Manchuria, where the Nurhaci rebellion originated. Actual control waxed and waned over time, and at times it was only "in name only", but obviously Ming would still strongly influence them.

Do you have any idea of how thick the armours would be? For either the samurai's plate or the brigandines?

ReplyDeleteNo idea on Samurai plate.

DeleteFolks on Cathay Armoury say average thickness of Qing brigandine plates is ~0.7mm.

Regarding the puttees worn by southern troops, would they have been worn on their own or over socks/stockings. Also, what material would they have been made of?

ReplyDeleteBoth, they can be worn alone or over stockings. They are made of cloth.

DeleteMy apology, I can't look up stuffs for the next few days for obvious reason, will get back to you later.

ReplyDelete