|

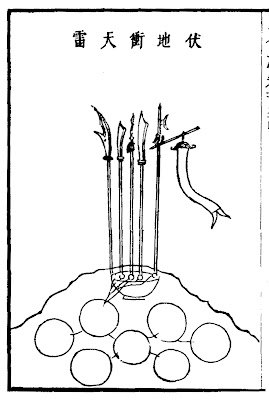

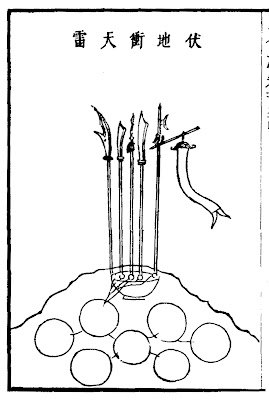

| Several weapons laid above the mine cluster, from 'Wu Bei Zhi (《武備志》)'. |

Fu Di Chong Tian Lei (伏地衝天雷, roughly translated to 'Ground-hiding, air dashing thunder') is a type of unusual land mine/booby trap, designed to take advantage of human greed and curiosity. The device is actually relatively simple, essentially several incendiary and poison smoke bombs buried underground along with an ember-filled basin. The bomb fuses are loosely tied to the butts of several pole weapons (baits), which are planted on top of the basin. If an enemy troop pulls out or otherwise disturb the weapon, the fuse will fall into the basin, thus igniting the bombs.

This land mine was made famous by the Deadliest Warrior television series (Season 2, episode 11), as one of the weapon that successfully bring down a curious French Musketeer. The actual weapon is actually quite different from its televised depiction. Like many anti-personnel mines, it is designed to disable, not outright kill, its victims.

What kind of people made these drawings? scholar-officials? and what were these military treatises for? to educate the next generation of government military officials?

ReplyDeleteEither scholar-official or military men. There were many reasons to write military manuals - pitching new ideas, personal interest/hobby, attempt to reform, pass down knowledge to the next generation, and sharing knowledge between contemporaries.

Deletethanks for your answer, i have another question if you dont mind

Deleteare the depictions of wokou realistic?

I noticed that you had spoken that most of them were Chinese in the 16th century, but their appearance is definitely Japanese (clothing, beard, haircut) as the artist wanted to portray in the paintings. They are portrayed in the same simple and primitive way in Korea as well as china:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Busanjinsunjeoldo.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:ChousenSyupei02.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tenshukaku_Suncheon.JPG

these paintings are the imjin war by Korean and chinese artists. I can not find much information about artists on the internet, the first is Korean and lived centuries after the war.

So all this is very strange, Japanese professional army from the sengoku war with the same appearance, to me it seems all a derogatory artistic convention (japanese were a wokou race to joseon korea and china until the 19th century, simple like that), the basic model for these wokou is probably how they were in the 14th century, starting as simple and mostly Japanese

Most Chinese depictions of Wokou were based on the Chinese impression of Japanese Wokou. They didn't get everything accurate down to the last detail, but the depictions are realistic in a "general" sense.

DeleteIMO there are several reasons for this depictions:

1) It should be noted that while many Wokou were Chinese,there were still a lot of Japanese, and many Chinese Wokou also dressed like Japanese.

2) Japanese wokou that engaged in pillage and banditry were proportionally higher than the overall ethnic ratio might imply. More Chinese wokou served as guide, scout, informant, behind-the-scene mastermind/planner, and manual labours. This would skew the preception of the victims.

3) Poor Chinese people that took the way of banditry usually hide in the mountains instead of going to the sea(ship is not exactly cheap), making Chinese bandits and Japanese Wokou easily distinguishable.

4) The "professional" Japanese army during Imjin War might not be as professional as you think. It was essentially a feudal-style army after all. About 30~60% combatants in the Japanese army were armoured in some fashion AT BEST (this already included samurai and ashigarus), add the non-combatants, the ratio become even lower.

Well,

DeleteWhen talking about pre-industrial societies, local artists tend to be far better at portraying their warriors than external sources (usually for the first time and barely do or care about, a matter of art markets ). I think there are many reasons behind it: ethnocentrism, depleting the military capabilities of opponents, "for the first time I see a foreign army and have so little time to portray this shock and collision of troops "(a painting that is almost a photograph in the detailing of all elements is the result of years of working on the same things, sketch drawings first and then paintings based on the drawings ), culture canons limiting your international reach, an event that happened a long time ago in a distant land and I must worry about the historical accuracy where I am selling, in other words a Chinese artist can not so easily deceive a Chinese patron, Chinese armors and Chinese weapons are in every corner of the nation.

this link is a fine example

http://www.williamturner.org/battle-of-trafalgar/

-look, Japanese byobu screen depicting ming cavalry and the battle of nicopolis (ottomans):

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ulsan_waesung_attack.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:NikopolisSchlacht.jpg

Chinese depictions of Wokou are generally more reliable than Imjin War Japanese army (not that there are many Imjin War painting to begin with) - large Japanese-style bows and Kobaya ship are not something that can be easily imagined without reference. The painter most likely witnessed/experienced Wokou raid first hand or otherwise spent effort studying them.

Deletehttps://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:ChousenSyupei02.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tenshukaku_Suncheon.JPG

This painting (it's different portions of the same painting) came from a painter that followed Ming general Liu Ting to Korea, and thus can be seen as a first-hand account. Its depiction of the geography and the layout of Japanese fort are fairly accurate (down to the triangular loopholes), so I am inclined to trust its accuracy in depicting Japanese troops as well.

OTOH, these paintings

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Busanjinsunjeoldo.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ulsan_waesung_attack.jpg

are painted by artists centuries after the fact, and thus much less reliable.

This comment has been removed by the author.

DeleteI used to think it was a simple yagura, but the shape is very strange, too thin for such a height, it seems that the Chinese artist understood the building as a pagoda in terms of height and area used , since Japanese-style castles never existed in china

Deletehere is the construction site:

http://www.noevir-hk.co.jp/magazine/Windows-Live-Writer/8ea3c80e0cda_78F7/080.jpg

http://tong.visitkorea.or.kr/cms/resource/10/1369810_image2_1.jpg

even with the castle having all that building foundation as you can see in the photos, it would never be tall like that, the ratio is strange

anyway yagura is a super relative term and nothing specific, any tower that is not the main tower of a Japanese castle could be called yagura

here yaguras of the osaka castle:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Osaka_Castle_rampart_in_1865.jpg

the main towers of hirosaki and matsumae would be yaguras for the castle wall of osaka:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hirosaki-castle_Aomori_JAPAN.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:MatsumaeJo.jpg

it is important to say that many original features of Japanese castles were lost in time through demolitions and fires, which usually means only the main tower survived (Japanese castles were true labyrinths) in urban planning and political reforms from the meiji era, the "secularized tozama daimyos" the new leaders of modern japan were violent progressive thinkers, something that continued well until the taisho political crisis

@henrique, it's true that Chinese didn't have stand-alone castles like the ones in Japan or Europe (since there was no feudal warrior caste in Imperial China), but they were nonetheless quite apt at building fortified cities and mountain forts.

DeleteAnd I think people shouldn't over-exaggerate the effectiveness of stand-alone castles. It doesn't really make a difference if a fortified city has such a castle or not. If the enemies had already broke through the walls and defenses, then a stand-alone castle won't save you the day.

DeleteIf you read Japanese, here's a good site that shows the layout of Suncheon castle in that Chinese painting and how it corresponds to the ruin today.

Deletehttp://www.iobtg.com/K.Suncheon.htm

It's safe to say that the castle is scaled down/shrunk to fit into the painting. That "padoda" is actually the Tenshu/main keep of Suncheon Castle, not just a random tower.

@The Xanian

DeleteActually, Chinese did build plenty of stand alone castles, although it's better to call them "fort" or "fortress" as there were no nobles or lords residing in it. This range from small garrisons with a hundred or so troops, to relay station/"glorified post office", to refuge castle in the case of enemy raid.

In fact, the definition of "castle" can be extremely shaky. For example, Waesong built during Imjin War are purely militaristic fortress complexes with zero consideration for them to be utilised as living space, yet are called "castle". OTOH, Indian forts are actually called "fort" instead of "castle" or "walled city" despite having the characteristic of both.

Yes, I understand that the definition of a "castle" can be shaky, but according to my best knowledge, Chinese rarely built stand-alone castles of any sort, it was always integrated with walls and other defenses.

DeleteNo, in fact Ming Dynasty built thousands of stand-alone forts, each manned by about 300~500 troops(often understaffed though) along its northern border, inside and sometimes outside the Great Wall.

Deletehttps://imgur.com/a/k7UJd4z

Here's some random pictures I pulled out of nowhere to show you just how many forts and watchtowers were there. Some of the larger squares are walled cities, towns, or major garrisons, the rest are forts and guard towers.

Those look more like fortified cities, garrisons, or outposts rather than castles imho.

DeleteI think it's safe to say that China didn't develop stand-alone castle towers to the same extent as Japan and Europe, since there was no feudal lords hence no need for them. It doesn't really make a difference, cause China had quite sophisticated walls and interconnected defense system, best exemplified by the Southern Song mountain forts built in the vicinity of Sichuan/Chongqing.

If by "interconnect", you mean they are physically connected by wall to each other, then no, they are stand alone. If you mean they are part a larger defense network, then yes.

DeleteThose are fortresses and watchtowers built for purely military purpose (although oftentimes civilians might move in and settle inside the forts), so there's indeed no feudal lords living in there. But otherwise I don't see many difference.

Actually China does have "stand-alone castle" similar to European and Japanese castles, other than "fortress" author have mentioned. There are mainly two types, first type is called 土樓(or 圍屋), some styles of 土樓 look quite similar to European/Japanese castles but they're mainly built by civilians; second type is Tibetan style mountain castles, there are hundreds of them in Tibet but not only limited in Tibet, such style has transmitted to China Proper during Qing dynasty mainly as temple buildings. Tibet maybe is not considered "Chinese" by some Westerners but they are part of China/Chinese now.

DeleteSome examples:

土樓

https://imgur.com/xeh6pks

https://imgur.com/HQ0EnLC

藏式城堡

https://imgur.com/ZwiquBy

https://imgur.com/omcXd9n

@Blogger01 I wouldn't consider Tu Lou to be exactly the same as European and Japanese stand-alone castle towers, as they serve different functions; the first is largely civilian, while the second is meant for feudal lords. And also they have different shape and design.

DeleteTibetan style mountain castles are more similar to European and Japanese ones IMO, but then again I feel that they didn't have much influence on Chinese defenses ("Chinese" in this case means the eastern part of China or China Proper). I'm not contesting the point that Tibet is a part of China now, but in the past it was rather isolated from the rest of China.

And not having stand-alone castle towers doesn't make Chinese defenses any inferior to European or Japanese ones. I made it very clear in my previous comments. Even if you have a huge stand-alone castle tower in the center of your city, once the walls are breached it wouldn't do too much on its own. The enemies can easily surround it and starve the people inside to death. Hence I feel the ancient Chinese did a right thing to focus more on the walls and outer defenses rather than building such termite-mound-like structures.

And last but not least, I'm a Chinese myself, I'm not a westerner.

Yes, China's ancient fortification engineer is still very brilliant regardless stand-alone castle or not. But some styles of Chinese fortification such as 土樓、圍屋、藏式城堡 do look and function quite similar to the "stand-alone castle" you depicted and imagined, that's fact and that's what I mainly want to show here, regardless you believe it or not. You cannot keep telling others there is no similar buildings in China because that's misleading and not true. I already show some real examples.

DeleteCastle-like buildings already exist even as early as Han dynasty, there are some buildings models excavated from Han dynasty tombs already look similar to stand-alone castle, 塢堡 is this sort of buildings, probably also is the ancestors of 土樓。

@Blogger01 Each one has his/her own opinions. I'm not going to argue with you on this, I'm just providing my own opinions. I think 藏式城堡 is more or less similar to European and Japanese castles, but 土樓 not really. And I don't think 土樓 is the same as Han Dynasty's 塢堡 either. The excavated models all had a squarish enclosure and a rather tall structure in the center. On the other hand, 土樓 is rather wide but not really tall, and it has a roundish enclosure.

Delete@TheXanian

DeleteThere are actually squarish Tulou too, although I think Wubi is closer to the Guangdong Hakka-style Sijiaolou. Not all Wubi have central watchtower either - I only recall seeing one pottery model with tower, while others are towerless.

On the other hand, there were European castles built by the gentry class as well, in particular pele towers along the Anglo-Scottish border.

I have another question if you dont mind

ReplyDeleteHow did the Chinese obtain sulfur domestically to make gunpowder? Since china has no volcanoes and those volcanoes would be sicily in europe..

The main foreign supplier of sulfur was Japan until the haijin policy?

An economic analysis of the song dynasty shows that the Chinese imported much sulfur from Japan. I just know that during the haijin period, the ryukyu islands were experiencing a golden age of prosperity in the maritime trade acting as intermediaries between china and japan as well as exporting sulfur to china and siam/thailand

China could derive sulphur from pyrite-based source, although it still import sulphur from Ryukyu and European traders.

DeleteThank you for sharing your knowledge. It is always difficult to find decent information about the history of Asia, even when talking about its major civilizations, i don't know if you like being annoyed with many questions,so just let me know after this last one

ReplyDeletewas the gunpowder revolution in China similar to the development of fortifications in the sengoku Japan? evolving into high and robust fortresses

明清北京城:

https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:CN-pek-deshengmen-tor.jpg#mw-jump-to-license

https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Deshengmenpic1.jpg#mw-jump-to-license

https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Siege_of_Peking,_Boxer_Rebellion.jpg#mw-jump-to-license

I started this blog to share knowledge, so I am glad someone is interested. So ask away, I will try to answer to the best of my knowledge (of course, I am still learning too).

DeleteI am unfamiliar with the influence of gunpowder weapon on Japanese fortification. As fare as I am aware, gunpowder did not influence the development of Chinese fortification to the same extend as Europe (i.e. star fort) etc.

There's an interesting theory called "Chinese Wall theory" that discusses why heavier siege gun never take off in China. The theory being that Chinese wall is sturdy enough to shrug off the heaviest of cannons as-is (the wall of Beijing actually withstood British bombardment during Opium war), thus the idea of heavy siege cannon died prematurely.

While the theory has its shortcomings (on why heavier artillery didn't develope in China), it demonstrates that Chinese fortifications can resist most gunpowder weapons up to twentieth century, so there's no need to drastically improve on it.

so the European-style cannons introduced into the ming and qing dynasties were useless? yeah, i am talking about jesuits as cannon-makers

Deletewell, prior to the sengoku period, Japanese fortifications followed the "mainland standard"

-Unlike in Europe, where the advent of the cannon spelled the end of the age of castles, Japanese castle-building was spurred, ironically, by the gunpowder revolution, not because of the technology itself, but more because of the socioeconomic context though

-In Korea, that would be Hwaseong Fortress and inspired by Chinese military engineering

-then in china, you had the new great wall of china built during the ming dynasty, with reinforced structure and design for cannons

I personally think the biggest reason why China got stagnant is because it simply had no match for its height in the far east or at least the conflict wasn't constant and intense year by year , the Ten Great Campaigns were nothing more nothing less pacifications of the Chinese borders. During the song dynasty, China had the most advanced military technology in the world as well as technology for civil affairs ( the song had a high rate of urbanization, a better urban economy is a better tax collection machine and consequently more money to invest in the armed forces, and radical social reforms, such as allowing the rise of the middle class that is always a victim of bullying by the aristocracy, after all the monarchs of Europe lost power or were executed (notably Louis XVI) by bourgeois revolutions, so I think there was a logical sense to repudiate the social mobility of the middle class), The Jin-Song Wars were two Chinas of equal weight at war for almost a century and during the warring States period, the Chinese had the most advanced siege weapons in the world, traction trebuchet for example.

The European guns were not entirely useless, since not every Chinese wall was built to the standard of Beijing wall (i.e. the Great Wall, for example, is puny by Beijing standard, despite its name). In fact the Manchus did bring down Chinese forts and cities with European cannons, and Ming actually constructed several European-style star forts and tried to incorporate angled bastion into existing fortifications.

DeleteThat being said, for the most part Chinese did not redesign their fortifications from the ground up (unlike the Europeans that phased out medieval-style castle in favour for star fort) - their existing walls still resisted cannons so there's no need for that. They simply made larger loopholes to accomodate heavier guns, and that's about it.

BTW, your speculation is similar to another competing theory, called "Chase hypothesis" (as it is propsed by Kenneth Chase), which is challenged by the "Wall theory".

Ahh... but i didn't mean evolutionary convergence, the linear evolution of history is totally illusory.Anyway thanks for your wisdom once again

Delete@henrique

DeleteI think I should answer your previous reply a little:

It is incorrect to think that Chinese firearm technology "went stagnant" due to it being the unchallenged superpower or enjoying relative peace. It just developed along a different line of thinking - one that optimised for keeping up and countering agile and unpredictable nomadic cavalry instead of batter down heavy fortifications.

Ten Great Campaigns were actually pretty big deal, Jingchuan campaign for example was a particularly hard-fought and expensive war.

BTW, after this discussion I looked up on the Hwaseong Fortress. Interestingly, it actually had some "inaccuracies" due to overly literal intepretation of the (extremely terrible) illustrations on Ming military manual, and the error had not gone unnoticed.

I wanna ask a question that is actually related to this post. How useful was the Fu Di Chong Tian Lei (or any other type of pre-modern Chinese landmine/naval mine)? Had they ever been deployed in battles?

ReplyDeleteAlthough not deployed "in battle" per se, land mines of various kinds were used very frequently during Ming period.

DeleteHello, could you maybe help me figure out the ethnicity of this character?

ReplyDeletehttp://gmzm.org/gudaizihua/%E7%9A%87%E6%B8%85%E8%81%8C%E8%B4%A1%E5%9B%BE/index.asp?page=113

The text describes "Mi Na Ke (密衲克)" people from Tibet.

DeleteI believe "Mi Na Ke" is the Chinese transliteration of "mi-nyay" (or is it the other way around?), which is what Tibetans called the Tanguts.