A couple days ago I chanced upon this

interesting article in Periklis Deligiannis's blog. It is nice to see that ancient Chinese military is gaining interest overseas, although (I presume) due to language barrier the author has to rely on questionable artist's renditions of Chinese shields for his article. While my blog isn't strictly academic, I think it'd be nice if I supplement his article with a more in-depth look on the evolution of Chinese shield.

A shield is known as

Dun (盾),

Pai (牌, can also be written as 排, but less common), as well as its archaic names,

Gan (干, note that this character cannot be written as 幹),

Lu (櫓), and

Bing Jia (秉甲, lit. 'Handheld armour'), in Chinese language. In modern usage, Chinese characters "Dun" and "Pai" are usually combined into a single word,

Dun Pai (盾牌). Shield had been an integral, if obscure, part of Chinese culture for thousand of years, not just for warfare but also for art, ceremony and religious purposes.

Shang Dynasty (1600 BC – 1046 BC)

As the earliest verifiable dynasty in Chinese history, archaeological finds of Shang shields are extremely scarce. There are only a few known types of shields in use during this period.

Lacquered hide shield

|

| Artist's rendition of a reconstructed Shang Dynasty shield unearthed at Yinxu. |

Shang shield was made of animal hide, usually coated in lacquer, mounted on a wooden frame. The shield was usually rectangular in shape and slightly wider at the bottom, although it could be made into a pointed oval shape as well. Shield surface was usually decorated with painting or multiple bronze ornaments, often with stylised cloud, animal or anthropomorphic motif.

Heater shield

|

| Illustration of the late Shang heater shield found in the M5 tomb at Yuquan, Baoji. |

Curiously, a type of large heater shield seems to be in use during late Shang period. Made of lacquered wood, the shield measured 43.3 inches (110 cm) in height, and 26.4 inches (67cm) at its widest point.

Western Zhou Dynasty (1046 BC – 771 BC)

Unfortunately, not much is known about the shields of Western Zhou Dynasty either. It appears that Shang-style hide shield was still in common use throughout the Western Zhou period, although they were increasingly supplanted by large wooden shield and the "double arc" shield.

Trapezium lacquered wooden shield (Early Western Zhou)

|

| Left: A trapezium wooden shield with a three-piece, spherical bronze ornament unearthed at Baoji, Shaanxi province. Right: A disc-shaped bronze shield ornament. |

This type of early Zhou Dynasty shield was made of a single piece of lacquered wooden plank. It measured about 43 inches (110 cm) in height, 19.7 inches (50 cm) in width at the top, and 27.5 inches (70 cm) at the bottom. Like Shang shield, it could be mounted with bronze ornaments.

|

| Large Western Zhou Dynasty bronze shield ornament that resembles a human face. |

Given its rather large size, it is suggested that this type of shield was used by infantry, although some argued that it was meant for chariot warfare.

Early "double arc" shield (Late Western Zhou Dynasty)

|

| Three Western Zhou Dynasty shields discovered at Shanmenxia, Henan province. Due to the fragile condition of these shields, they are not only partially excavated. |

By late Western Zhou period, Chinese shield was on its way crystallising into the quintessential "double arc" shield (see below) that would remain in widespread use for centuries to come. This type of shield was made of lacquered animal hide mounted on wood or rattan frame. Measured about 31.5 inches (~80 cm) in height and 16 to 19 inches (~40 to 50 cm) in width, this type of shield already featured the characteristic "double arc" shape of later shields, yet still retained bronze ornaments like earlier shields.

Eastern Zhou Dynasty/Spring and Autumn and Warring States period ( 770 BC – 221 BC)

Eastern Zhou was turbulent period characterised by the collapse of central authority, frequent warfare and social upheaval, but also

great cultural and intellectual expansion and technological advancement. This period also saw the emergence of iconic "double arc" shield.

"Double arc" shield/Shuang Hu Dun (雙弧盾, lit. "Double arc shield')

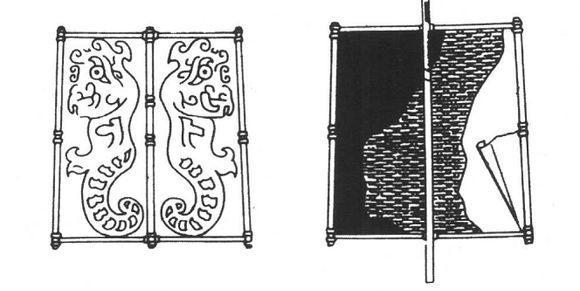

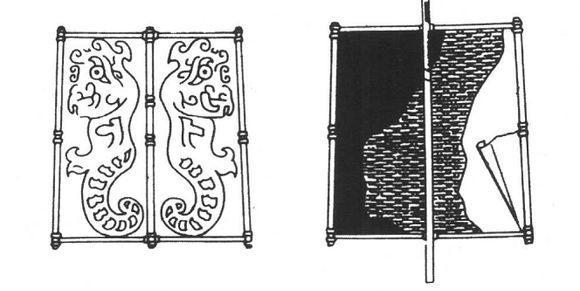

|

| Warring States period Shuang Hu Dun currently kept at Jingzhou Museum. At 36.4" × 23", this particular shield is one of the largest of its type, almost rivalling a Roman Scutum in size. |

So named because of its distinctive shape, this type of shield was the most ubiquitous "Chinese" shield. Shuang Hu Dun could be made of lacquered hide mounted on a wooden frame, lacquered wooden plank, or wood with lacquered hide facing, although hide version appears to be the most common. Most Shuang Hu Dun were centre-gripped, medium-sized shields, roughly 23.5 inches to 31.5 inches (~70 cm to ~80 cm) in height and 13 inches to 23.5 inches (~30 cm to ~60 cm) in width.

It is still not fully understood why ancient Chinese people chose to design their shields into such complex shape.

Rectangular lacquered wooden "tower shield" (Warring States period)

|

| Large "tower shield", Warring States period. |

Another type of shield in use during this period was the so-called "tower shield". This type of shield was made of several lacquered wooden planks joined together with rattan, with lacquered linen facing. It featured a centre grip as well as a bronze shield boss. This type of shield measured roughly 36.14 inches (91.8 cm) in height and 19.53 inches (49.6 cm) in width.

Qin Dynasty (221 BC – 206 BC)

A short-lived dynasty, Qin period did not see many development in Chinese shield design.

"Double arc" shield/Shuang Hu Dun

|

| Full-sized hide shield recently discovered in the Mausoleum of the First Qin Emperor. |

Qin troops continued to rely on tried-and-true Shuang Hu Dun for personal protection. It is not know if they still used Warring States "tower shield" or not, due to the lack of archaeological finds.

Western Han Dynasty (202 BC – 8 AD)

Although "double arc" shield continued to see common use, Western Han period saw the emergence of a new type of buckler.

"Double arc" shield/Shuang Hu Dun

|

| An early Western Han terracotta warrior equipped with Shuang Hu Dun, Yangjiawancun, Shaanxi, China. |

|

| Several model shields detached from the terracotta, showing relatively simple decorative patterns. |

Western Han period Shuang Hu Dun was virtually unchanged from its Warring States and Qin predecessors, although the abstract decorative pattern on the shield surface became simpler and cleaner, following the Han Dynasty artistic trend.

Nevertheless, Shuang Hu Dun also rapidly became larger during Western Han period.

|

| Left: Terracotta warrior from Yangjiawan, Shaanxi, likely dated to the period right after the founding of Han Dynasty. Right: Terracotta warrior from Shanwangzhuang, Shandong, early-to-mid Western Han period. Note the rapid increase in shield size as well as heavier body armour. |

Chinese parrying buckler/Gou Rang (鉤鑲)

A Gou Rang was a roughly rectangular-shaped iron buckler, only slightly larger than a man's fist, that became popular during Han period. It had a vertical iron bar handle, and came with two long parrying hooks mounted at the top and bottom of the buckler, as well as a punching spike mounted on the face of the buckler. The top hook was usually longer and sharper than the bottom hook.

|

| Stone rubbing of a Han period brick relief, depicting a duel. Figure on the right can be seen parrying a Ji halberd with his Gou Rang. |

Gou Rang was often used in a pair with a sword, a short-handled

Ji (戟) halberd, or a

Shou Ji (手戟, lit. 'Hand halberd'), essentially a head of a

Ji without its shaft. The design of Gou Rang is immediately reminiscence of Indian

madu buckler as

uboko and

izolihauw used in

Nguni stick fighting among others.

Very rarely, a Gou Rang with its parrying hooks and punching spike removed could be fused into the grip of a lance or a sword, serving as hand protection (i.e. vamplate or basket hilt) for the weapon.

Rectangular shield with rounded top

|

| Western Han wooden burial figurine carrying a slightly deformed shield. Excavated from Yandaishan, Jiangsu province. |

This type of shield can perhaps be seen as an intermediate form between the Western Han Shuang Hu Dun and Eastern Han long shield, as it was of similar size to the former, but shared the same shape to the later.

Turtle shell shield/Gui Dun (龜循, lit. 'Turtle shield')

A unique shield made of lacquered turtle shell was discovered at Hubei in 1978. This shield appears to be one-of-a-kind, and is possibly intended as grave goods, rather than for practical use.

Eastern Han Dynasty, Three Kingdoms period and Jin Dynasty (25 AD – 420 AD)

"Double arc" shield was still used during this period, although it was losing popularity, being gradually displaced by a variety of newer designs. Shield became longer and larger, and the complex shape of "double arc" shield gave way to simpler shape. This period also saw the emergence of strapped shield.

Gou Rang buckler was also used during Eastern Han period and early Jin period, but disappeared afterwards.

Strapped "Double arc" shield/Shuang Hu Dun

|

| Eastern Han figurine with a strapped-on Shuang Hu Dun, Zhaohua Han Dynasty Museum. |

Shuang Hu Dun, both centre-gripped and strapped variety, were still used throughout Eastern Han to Jin period, although they were not as popular as they once were.

While the earliest evidence of strapped Shuang Hu Dun comes from Eastern Han period, it is likely that this type of shield was already in use during Western Han period, since there are numerous mentions of "Ji halberd and shield" and "long spear and shield" in historical text.

|

| Section of a Jin period mural depicting an army on the march. The horizontal orientation of these shields may indicate a strapped design. |

Long shield with prominent spine

|

| Eastern Han period brick relief depicting a shielded soldier escorting a prisoner of war. |

|

| A kneeling Wu Kingdom figurine with a shield that resembles a simplified and elongated Shuang Hu Dun. |

|

| A Western Jin period warrior figurine holding a long shield. |

Long shield became the dominant shield type during this period. Long shields varied greatly in size and shape. Rectangle/trapezium with rounded or pointed top appears to be the most common during Eastern Han period, while oblong shape became more common during Western Jin period. They were presumably made of wood with lacquered hide facing, although this cannot be confirmed due to lack of findings of actual shield.

Most long shields were centre-gripped.

One reason I can see for using the double-arc shield design is that the notches on the side could be used to help hold pole-arms in place while in infantry formations. By resting the shaft of the pole-arm on the notch maybe the soldier is able to keep it steady and put less strain on the arm holding the weapon. European jousting shields sometimes had this sort of cavity to hold the lance in place. Then again maybe the design had some other purpose or was simply chosen for its aesthetic.

ReplyDeleteYes I am aware of that possibility, although it begs the question of why there are so many notches on one shield,

DeleteOthers suggest that the notches are used to trap enemy weapon.

I think they are used as "stab thru holes" for whatever weapon they had, making it easier to stab without exposing the arm, and the holes make it easier to see past the shield when in direct combat. I also think, that the 4 grooves are potential attacking locations: the lower grooves for low/groin thrusts, the top for upper thrust, and the sloped half for overshield attacks.

DeleteI think they only brought the rectangular shield during the warring states because it was cheaper, and they were going thru a crisis that probably didn't allow time to create the complex double arc shields. Hence why the rectangular shields disappeared during the Qin dynasty, when the warring states period ended, because they had the time to produce these complex shields.

Could also be that some warlord really liked tower shields...

Thanks for your input.

DeleteAs for Tower shield, it was used alongside Double Arc shield though, and it doesn't look like a rush job (the metal boss probably makes it more expensive and harder to make than typical double arc shield).

A small trivia: The large pavises as depicted in the movie "Red Cliff" are based on the kneeling Wu Kingdom figurine pictured in my blog post. Actual shield was nowehere near as large as the movie depiction and most definitely didn't glow in golden colour though.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteI would be really interested to see more pictures of the grip on the double arc shield. I'm trying to recreate one, using modern materials. I've been using one in SCA combat with the correct double arc profile, and it does play interestingly when deflecting attacks from swords. My trouble is mounting the grip correctly, to get the balance correct. At the moment the grip I use just protrudes from the back, it isn't recessed as it seems to be on the extant version.

ReplyDeleteI will see what I can find for you. Stay tuned.

Deletehttps://imgur.com/a/HMFjpjw

DeleteThank you! Would you like me to send pictures of my modern recreation for SCA combat when I have my new shield put together? I also plan to do a short write up on how the shield functions. I've been fighting with one of correct profile, but only serviceable grip, for awhile, and the bumps created by the arcs play well to its defensive capabilities.

DeleteI'd love to. You can email the pictures to me.

DeleteI can't really see the usefulness of the double arc shield compared to other designs. It provides neither protection from missiles nor coverage enough for a passive defensive stance. Successful use would've required a dynamic fighting style which doesn't fit the massive levy armies of the time.

ReplyDeleteI don't see recruitment method having that much effect on the fighting style of the recruits - rattan shield for example is just as dynamic, but the arts was pretty common among the common people. If those people were levied, they bought the skills with them into the army.

DeleteJust a feeling that levies didn't have access to the time and funding to properly train them, so a simple, protective shield would've done more good. And I'm not entirely certain if martial arts were super widespread throughout the populace, at least in Han dynasty times.

DeleteI read somewhere that most infantry in that time were either levied spearmen who didn't carry shields, or trained crossbowmen. I have no idea how accurate that is though.

Double arc shield was developed during Eastern Zhou (Spring & Autumn + Warring States), an era of frequent warfare. I will be very surprised if martial arts wasn't widespread back then. Also, I don't really buy the "mass poorly trained levy" idea on ANY Chinese dynasties.

DeleteIt is apparent that the "mass levy" idea really didn't apply to dynasties like the Ming and the Qing, but given that the warring states fielded armies so large that it would make their western contemporaries blush, it would be hard to imagine all those tens of thousands to be trained to a certain level. As for shields, it seems surprising that such a small shield was in use when the Chinese's enemies, each other and the Xiongnu, were all heavily missile based

Delete@Alex Cheng, Mass levies does not indicate poor quality of troops. The Roman army of the early to mid Republic was an entirely massed levied militia, and these armies defeated the armies of powerful states such as Carthage, Macedon, and Seleucid. The Romans defeated their greatest enemies with massed levies - many years before the Marian reforms that transitioned the army into a professional standing army that relied more on volunteers.

DeleteFurthermore, well trained levied militias and professional troops existed during the Warring States era. Training and equipment were often provided by the state. During the Western Han era, militias were trained for a year and served for 1 or 2 years. That is more than enough training if we consider the Roman troops were trained for 4 months according to De re Militari by Vegetius.

Do you know the Native Chinese name of Long shield of Han dynasty? I wonder how it's called.

ReplyDeleteI doubt such a name even exists - even "double-arc shield" is a modern name. Han people back then probably called it with the generic term for "shield" in Chinese.

DeleteHello, 春秋戰國,

ReplyDeleteI found a series of pictures of jade carving supposedly from the Shu Kingdom of Sanxingdui.

http://www.coant.com.cn/upload/2015/1/7103655375.jpg

http://www.coant.com.cn/upload/2015/1/71037816.jpg

It show shield with holes for trapping enemy weapons and it also show use of polearms by 1200-1000 BC.

I don't know if they are imitation, but I know that jade objects last a long time so they look like newly made.

If it is authentic, then the Sanxingdui culture weaponry is very advanced for its time.

Those are clearly fakes.

DeleteThank you, but do you know an article or news that show that these are fakes?

DeleteI have my suspicion about those things, however, I have also heard too much claim of fake history whenever a debate when into China's favor.

Also there are some Chinese artifact that looks like it was made in the modern era like this Warring States crystal cup.

https://i.pinimg.com/originals/28/f6/66/28f6668505375e7522536436014f4fea.jpg

Had it been polished before display, would people thought it would be from the Warring States period?

I am not aware of any news or article specifically written to debunk this.

DeleteHowever, the carvings on the disc are clearly made with a isometric POV, and there are a few flags and many soldiers depicted as partially "offscreen". I seriously doubt those are common practices back in the day.

Thank you for your opinion.

ReplyDeleteThe reason why I consider this as not fake yet is because of some photo where the jades are displayed in a museum like setting.

Here is the rest of the jades

http://www.coant.com.cn/contents/7/7059.html

https://31562jp.wordpress.com/古蜀文明の謎-三星堆遺跡%E3%80%803/

Some of them do really look like modern souvenirs.

But I do think that some of them could be authentic.

Is it profitable to fake something like this?

https://31562jp.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/1504483750618894344.jpg?w=833

I specifically refer to the disc as fake. The more discs I see, the more dubious they look to me.

DeleteA few figurines in there are probably fakes as well, although I can't say with as much onfidencec as with the discs.

What was the most common weapon to use with a shield in china?

ReplyDeleteUmm, sword and spear?

Delete