After receiving Yang Hao's order, Gwon Yul ordered Joseon army to launch

the feint attack. Joseon cavalry rode around Dosan Fortress and fired

warning shots with their guns constantly, forcing the Japanese to be

constantly on their toes, as well as baiting them to waste their shots.

While the feint attack was ongoing, Joseon army also launched a probing

attack on the gate of sannomaru of Dosan Fortress. Katō

Yosaemon, who was in charge of the defence of sannomaru,

deployed taketaba (たけたば or 竹束, lit. 'Bamboo bundle') and ordered his

arquebusiers to repel them. While the attack was unsuccessful, Joseon

troops managed to pile up firewood at the base

of sannomaru before retreating, hoping that they could

set fire to the fortress once heavy rain subside.

At around 4 pm, Yang Hao once again sent Kim Ung-seo and Japanese

defectors to Dosan Fortress to call for surrender, although this time they

were simply ignored. As the sky turned dark, Yang Hao, concerned that

Japanese troops may attempt another night raid, ordered Ming troops to

stand guard over the night, and even specifically ordered Joseon troops to

stand guard together with their Chinese counterparts. On top of that, Yang

Hao also sent Kim Ung-seo and his Japanese defectors to patrol the water

wells near Dosan Fortress and attempt to entice defection of Japanese

troops that came to collect water. Despite all these defensive

arrangements, Yang Hao was still paranoid about the lie about Katō

Kiyomasa's whereabouts, so he repeatedly summoned Korean captives for

questioning to ascertain that Katō Kiyomasa was really inside Dosan

Fortress. Afterwards, Yang Hao and Ma Gui returned to the main siege camp

at Hakseongsan to oversee the construction of semi-permanent thatched

shelters (up until now, entire Ming army including its highest-ranking

commanders simply camped in the wild).

Just as Yang Hao predicted, Katō Yosaemon and Kondō Shirō Goemon sallied

out of the fortress under the cover of night to launch a night raid on

Ming camps, although they quickly discovered that both Ming and Joseon

troops were on high alert and had to abort the plan. However, as they

were returning to Dosan Fortress, they preemptively burned away the

firewood.

Day 6: A turn for the worse

February 3, 1598 (25th year of Wanli reign, 12th month, 28th

day)

|

|

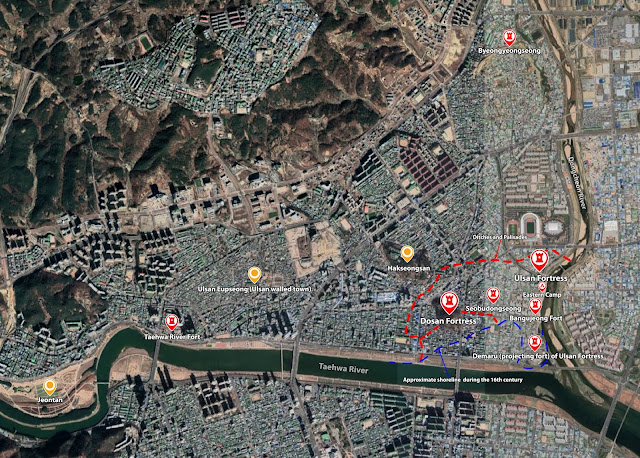

Ming army launched an artillery barrage against Dosan Fortress

from across Hakseongsan (click to enlarge).

|

The heavy rain slowly subsided on the sixth day. According to some

Japanese sources, on this day some Ming troops moved their cannons to

Hakseongsan and launched an artillery barrage across the hill into Dosan

Fortress. Several Japanese troops were pulverised by cannon fire,

causing a panic to spread. Japanese troops attempted to run for cover,

but they were stopped by Katō Kiyomasa, who remained unfazed even

as some cannonballs landed near him. Katō Kiyomasa's calmness and

non-reaction misled Ming artillerymen into believing that their shots

missed the mark, so they adjusted their guns and launched the next salvo

with a higher trajectory, overshooting Dosan Fortress. It was at this

point that Katō Kiyomasa ordered his troops to act as if they were

getting shot at to further deceive the Chinese. As a result, Ming

artillerymen continued to fire their cannons using high trajectory,

missing most of their shots.

It should be noted that Chinese and Korean sources make no mention of

such artillery barrage taking place, as Ming army left its artillery

train behind (to its own detriment). If this artillery barrage actually

happened at all, it is likely that Ming artillerymen only employed a few

lightweight anti-personnel pieces such as

Fo Lang Ji (佛狼機)

for suppressive fire, rather than heavy artillery for wall-smashing

bombardment. Incidentally, some Korean sources do mention Japanese

troops shooting at Hakseongsan with "cannonballs as large as chicken

egg", presumably from an ō-deppō (大鉄砲) handheld matchlock cannon

and nearly hitting Yang Hao (he was equally unfazed), although no

specific date was given for this barrage. Perhaps Japanese barrage was a

counter-barrage in response to Ming bombardment, although the

possibility that these were unrelated incidents, or even propagandistic

embellishments that did not actually happen, cannot be ruled out.

Like the days before, Joseon troops launched an assault on Dosan

Fortress, and once again they were repelled by the Japanese. At around

11 am, yet another Japanese flotilla arrived at Ulsan and began sailing

closer to Dosan Fortress. Japanese troops inside the fortress soon

noticed something unusual about today's flotilla: instead of Katō

Kiyomasa's own banners, these ships were flying the

uma-jirushi (馬印, lit. 'Horse insignia') of Yamaguchi Munenaga

and Mōri Katsunobu.

This can only mean one thing—new Japanese

reinforcement was under way.

|

Yamaguchi Munenaga and Mōri Katsunobu's flotilla sailing

from Seosaengpo Fortress to Ulsan Fortress (click to

enlarge).

|

|

|

Ming troops at the river bank engaging Japanese flotilla (click to

enlarge).

|

As it turned out, before Katō Kiyomasa rush back to Dosan Fortress on

January 29, 1598 (Day 1), he sent out messengers to surrounding Japanese

commanders to call for aid. Japanese commanders at Yangsan and Busan,

being the closest to Seosaengpo, received the call on January 30, 1598

(Day 2) and dispatched their relief forces the soonest. Yamaguchi

Munenaga (from Yangsan) and Mōri Katsunobu (from Busan) arrived at

Seosaengpo on the evening of February 2, 1598 (Day 5), and sent out

their ships the next day. Since both of them had only just arrived, the

flotilla only scouted the area and briefly communicated with Japanese

troops trapped inside Dosan Fortress using flag signals before reporting

back to Seosaengpo. Nevertheless, signs of incoming help raised hopes

for Japanese troops inside Dosan Fortress. At around 6 pm, additional

relief forces led by Kuroda Nagamasa, Ankokuji Ekei, and Takenaka

Shigetoshi also arrived at Seosaengpo.

Meanwhile, Katō

Kiyomasa's messenger only just arrived at Suncheon Fortress (which was

farther away from Seosaengpo). Incidentally, construction of Suncheon

Fortress was completed on the same day, and Shimazu Yoshihiro (島津義弘)

with his son Shimazu Tadatsune (島津忠恒) were hosting a celebratory

feast with other Japanese commanders inside Suncheon Fortress when

they received the news about Ulsan under siege. Due to Xing Jie's

diversionary attack, Japanese commanders at Suncheon Fortress were

reluctant to send out their full force to relief the siege. Kakimi

Kazunao even specifically ordered Shimazu Yoshihiro to stay behind

to defend the fortress, and only went to Ulsan with his own troops.

Perhaps not wanting to lose reputation for not sending out

help, Shimazu Yoshihiro later wrote a letter to his

nephew Shimazu Toyohisa, asking him to go to Ulsan in his

stead. He also dispatched a few retainers and 50 arquebusiers to

reinforce Shimazu Toyohisa's 500 troops.

The rain finally stopped by nightfall, only to be replaced by

strong westerly winds. The freezing winds took a serious toll on Ming

troops, in particular Zhejiang infantry guarding the river banks. At

midnight, Katō Shigetsugu (加藤重次), Shōbayashi Hayato (庄林隼人) and

Kondō Shirou Goemon (近藤四郎右衛門), leading a contingent of 100

mounted samurai and 300 arquebusiers, sallied out of the eastern gate of

ninomaru of Dosan Fortress to harass Ming army. They

launched a few volleys of fire arrows and arquebus shots at Ming camps

at the east side of Dosan Fortress before turning back.

Day 7: Renewed attack

February 4, 1598 (25th year of Wanli reign, 12th month, 29th

day)

The strong wind that began to blow since last night persisted into the

seventh day of the siege. At dawn, Yang Hao ordered Ming army to gather

more firewood in preparation for another attack on Dosan Fortress, as he

felt the strong wind could be helpful in spreading the fire. At noon,

another 26-ship flotilla from Yeompo arrived at Ulsan and began

approaching Dosan Fortress, and once again Ming troops guarding the

river banks bombarded the flotilla with cannons. While both sides were

busy exchanging fire against each other, one samurai and a few of his

followers suddenly dashed out of Dosan Fortress to the river bank and

began shouting to the flotilla. Although he did not understand Japanese,

Yang Hao was alerted enough that he immediately dispatched Ming Right

Division to reinforce Wu Wei Zhong's Zhejiang infantry at the river

banks, as well as asking them to be extra vigilant. Ming army repelled

the flotilla at around 5 pm.

|

Japanese flotilla sailing from Yeompo naval base to Ulsan

Fortress for the fourth time (click to enlarge).

|

At around 6 pm, Yang Hao ordered Ming army to get ready for the attack.

Ming troops silently approached Dosan Fortress under the cover of

twilight, carrying firewood and with their shields readied.

Unfortunately, they were spotted by Japanese sentries as they came near

the palisades of Dosan Fortress, and were forced to retreat after

suffering heavy casualties under fusillades of arquebus fire. By

nightfall, Ming and Joseon army launched a second attack with much

greater ferocity than before, ignoring casualties inflicted by Japanese

arquebusiers and moving closer to Dosan Fortress. Realising that they

may not be able to resist the assault with arquebus fire alone, Japanese

defenders were forced to bust out the ō-deppō to supplement their

firepower. The battle raged on until around 9.30 pm before Ming army

retreated.

After today's attack, Yang Hao appeared to have a

change of mind. He probably felt that trying to take the fortress by

force was no longer practical after days of consecutive failures, and

wanted to adjust his strategy to that of encirclement and

investment. To this end, Yang Hao ordered his troops to upgrade their tents into

semi-permanent thatched shelters, and urged Gwon Yul and Yi Deok-hyeong

to hasten the next delivery of supply. Ma Gui suggested Yang Hao to lift

the blockade of one side of Dosan Fortress, then ambush the Japanese as

they came out. However Yang Hao rejected his idea.

Late into

the night, a small Japanese ship sneaked back to Dosan Fortress,

presumably due to the shouting communication earlier in the day. About

30 Japanese troops came out of Dosan Fortress and attempted to board the

ship. However, they were immediately attacked by Ming troops laying in

ambush. After a brief skirmish, Wu Wei Zhong's Zhejiang infantry managed

to behead six Japanese troops, whereas Ming Right Division troops

beheaded one. The rest ran back into Dosan Fortress.

In the

meantime, Mōri Hidemoto finally arrived at Seosaengpo at around 4 pm.

Japanese commanders at Seosaengpo held a war council that night to

decide their next course of action—whether to send a relief force to

Dosan Fortress immediately, or wait for further Japanese reinforcement

to arrive before sending out help. They concluded that an advance party

would be dispatched the next day, but the majority of Japanese forces

should stay and wait for more reinforcement.

Day 8: Living hell

February 5, 1598 (25th year of Wanli reign, 12th month, 30th

day)

It was February 5, 1598, last day of the year on Lunisolar calendar,

and the eighth day of the siege. Dosan Fortress already ran out of

food and water, and days of exhaustion, starvation, dehydration, and

freezing winter turned the fortress into a living hell (in fact the

Japanese only managed to survive this long thanks to the heavy

downpour of the past few days alleviating some of their water shortage

problems). Japanese troops had slaughtered the last of their pack

animals for food, and resorted to munching paper and dirt on the wall

for subsistence, as well as drinking urine to sate their thirst. They

were so desperate that some sneaked out the fortress to scavenge for

leftover field ration on the frozen corpses of their fallen

comrades-in-arms, while others drank water from ditches full of dead

bodies and blood. Only the highest ranking Japanese commanders could

have some semblance of meal, but even them had to ration their food

into pinches of rice. To stave off the cold, samurai, ashigaru, and

levied labourers disregarded their social standing and bunched

together in groups of dozens of people each. Despite their best

effort, incidents like people unexpectedly drop dead due to the cold

or froze to death in their sleep were daily occurrence. In his diary,

Ōkōchi Hidemoto recorded that he was malnourished to the point of

becoming literal skin-and-bone, and that a friend of his, who he

described as a large and burly man, refused to take off his armour to

conceal his rapidly emaciating frame.

While Japanese troops were suffering inside their fortress, Chinese

troops besieging them hardly fared any better. Despite some Korean

sources claiming that Ming army was well-supplied, the reality of Korean

logistics mismanagement cannot be made more apparent by multiple reports

from Joseon officials actually present at the frontline. To sum it up,

Yi Yong-sun (이용순 or 李用淳), overseer of the entire supply operation,

ignored his duty and returned to Gyeongju for no reason, and many Joseon

quartermasters were not doing their jobs at all. Ming army ran

dangerously low on food, and the warhorses, which had not eaten anything

for nine straight days, were dying by the hundreds. In fact the

situation was so bad that Jang Un-ik and Yi Deok-hyeong, two of the

highest ranking Joseon officials, had to take the matter into their own

hands and do the jobs of their inferiors. Despite their best effort,

they only managed to secure stable food supply for the highest ranking

Ming commanders, Yang Hao and Ma Gui (as the Koreans were afraid to

anger them). Even Ming commanders had depleted their salt and sauce

provisions with no hope of resupply, and the rank and file were simply

left to their own devices. The death of more than a thousand warhorses

(and rapid weakening of the rest) had a disproportionate impact on

combat readiness of the predominantly-mounted Ming army, not to mention

the exhausted and starving Ming troops exposed to freezing temperature

for days. Joseon officials were painfully aware that given the sorry

condition of Ming army, the entire siege campaign would be thrown into

jeopardy the moment Japanese reinforcement show up. Unfortunately, they

were incapable of salvaging the situation.

|

|

Japanese advance party and flotilla from Seosaengpo went to

Ulsan (click to enlarge).

|

Leaving aside the suffering of both armies, by 7 am in the morning,

Japanese advance party from Seosaengpo had arrived at Ulsan by land and

set up a camp on a hill known as Songsan (송산 or 松山), some 12 km away

from Dosan Fortress. Meanwhile, another Japanese flotilla also arrived

at Ulsan. Unlike previous days, it did not attempt to break through the

encirclement, but waited patiently on the river.

Later in

the day, Katō Kiyomasa wrote a letter to Ming army, informing the

Chinese of his intention to negotiate for surrender. He requested

permission to let in a Buddhist monk on the Japanese flotilla to serve

as translator and draft the written agreement, on the pretense that no

one in Dosan Fortress spoke Chinese. On the Ming side, Yang Hao already

knew that taking Dosan Fortress by force would be difficult, and his

troops were in a terrible shape, so when he received news that the

Japanese were trying to sue for peace, he gladly accepted it and let the

Buddhist monk enter Dosan Fortress. After some back and forth

communication, both sides agreed to hold a peace talk in three days, in

which Katō Kiyomasa was required to personally attend. Little did

Yang Hao know, the flotilla was not Katō Kiyomasa's, but a scouting

flotilla sent by Mōri Hidemoto, Kuroda Nagamasa, Yamaguchi Munenaga and

Takenaka Shigetoshi. It had already made contact and coordinated with

Japanese troops inside Dosan Fortress using flag signals beforehand, so

when the "Buddhist monk" was allowed to enter the fortress, he brought

with him the news of the arrival of Japanese relief force, which boosted

the morale of Japanese troops tremendously. The flotilla returned to

Seosaengpo afterwards.

(It should be noted that Korean and Japanese sources strongly disagree

on which side initiated the negotiation. Many Japanese sources claim

that it was the Chinese that initiated the peace talk after being

repeatedly defeated, and the peace talk was initiated on Day 7 rather

than Day 8. However, it makes no logical sense that the Chinese would

sue for peace during the day and then immediately attack in the same

evening, so Japanese version of the event simply cannot be true. This

logical problem did not go unnoticed by Japanese historians either.

However, instead of acknowledging the mistake, later Japanese sources

such as Nihon Senshi simply alter the time of the Day 7 attack from

evening to morning to forcibly harmonise the discrepancy.)

By noon, additional reinforcement led by Nabeshima Naoshige and his son

Nabeshima Katsushige, as well as Hachisuka Iemasa, Ikoma

Kazumasa, Katō Yoshiaki, Wakisaka Yasuharu and Hayakawa

Nagamasa, also arrived at Seosaengpo.

Later in the night, Katō Kiyomasa dispatched two parties out of

Dosan Fortress to conduct a so-called "night raid" mission. Despite the

name, they were actually foragers desperately looking for food and

water. One of the parties, of about 30 men strong, headed straight to a

water well near the outskirt of Dosan Fortress to collect water.

Unfortunately, they ran into Korean commander Kim Ung-seo and a

contingent of defected Japanese troops under his command, who were

guarding the water well since Day 4. Kim Ung-seo immediately attacked

them, killing five and captured another five. Yang Hao was notified of

the incident and immediately ordered the captives to be brought to him

and interrogated. After witnessing the severely famished captives, and

learnt of the dire situation inside Dosan Fortress (according to the

captives, Dosan Fortress had completely run out of food and water, and

out of about 10,000 starving souls still alive, less than one thousand

were combat capable.), Yang Hao was finally able to put his mind at

ease, confident that the Japanese wouldn't be able to hold out for much

longer.

Day 9: An uneasy new year

February 6, 1598 (26th year of Wanli reign, 1st month, 1st

day)

Korea welcomed its Lunisolar New Year in tension and uneasiness.

Nevertheless, Joseon King Yi Yeon (이연 or 李昖, more commonly

known as King Seonjo) personally visited Xing Jie to give him a new year

greeting. Xing Jie gifted the king with two calligraphic scrolls to

congratulate him in advance on the victory of Imjin War, in return King

Yi Yeon wished him a prosperous new year and congratulated him in

advance on the victory at Ulsan. The two had a great time

together.

In stark contrast, Ryu Seong-ryong went to Ulsan at dawn to give Yang

Hao and Ma Gui his new year greeting only to be met with cold shoulder,

as no one at the frontline was in any mood of celebration. Yang Hao

urged him to return to Gyeongju as soon as possible to send in the next

delivery of supply, going so far as to declare that the supply problem

was so critical that even a single dan of rice should be

delivered to the frontline at the double.

The Japanese however were in even more sombre mood compared to the

Chinese and Koreans. Dosan Fortress was literally hanging by a thread,

with less than 6,000 Japanese troops alive and casualties mounting at an

alarming rate due to starvation and freezing temperature. Katō Kiyomasa

and Asano Yoshinaga wrote a joint distress letter to seven

Japaneses commanders, among them Kobayakawa Hideaki and Mōri

Hidemoto, to explain the dire situation inside the fortress. They stated

that if reinforcement didn't come soon, the entire garrison of Dosan

Fortress was prepared to fight to the last man. If the fortress fell,

they hoped that the recipients of the letter can at least bring the news

of their valiant last stand back to Japan.

|

|

Zu Cheng Xun crossed Taehwa River (click to enlarge).

|

Later in the day, Ming mounted scouts detected Japanese presence at

Songsan. Since Japanese advance party was few in numbers, Yang Hao only

ordered Zu Cheng Xun (that guarded the northern bank of Jeontan) to

cross Taehwa River to join force with Wu Wei Zhong's detachment to

monitor Japanese activities from afar.

Meanwhile, Shimazu Toyohisa arrived at Eonyang and captured Eonyang

Fortress after defeating a small garrison there. At around 2 pm, Kakimi

Kazunao and Kumaga Naomori arrived at Seosaengpo. They were

followed by Chosokabe Motochika, Nakagawa Hidenari, Ikeda

Hideuji, Ikeda Hideo, Mōri Katsunobu, Mōri Katsunaga, Akizuki

Tanenaga, Takahashi Mototane, Itō Suketaka and Sagara

Yorifusa, who arrived in succession at around 4 pm. Later in the

evening, two retainers of Asano Yoshinaga and one retainer of Ōta

Kazuyoshi slipped out of Dosan Fortress and delivered the distress

letter to Seosaengpo, arriving by nightfall. Upon receiving the

letter, Japanese commanders at Seosaengpo held an emergency

meeting, and decided that they couldn't wait any longer—the relief force

would immediately depart the next day. Mōri Hidemoto also initiated

a joint letter, signed by Japanese commanders at Seosaengpo, to report

the current status of Dosan Fortress and Seosaengpo to Hideyoshi.

Day 10: Reinforcement

February 7, 1598 (26th year of Wanli reign, 1st month, 2nd

day)

|

|

Japanese relief force marched to Ulsan while Japanese flotilla

sailed to Yeompo Naval Base (click to enlarge).

|

On February 7, 1598, the Japanese army that gathered

at Seosaengpo finally made its move. The massive relief force

departed for Dosan Fortress by both land and water route. On land,

Nabeshima Naoshige and Kuroda Nagamasa led the First Division and

departed first, with Hayakawa Nagamasa, Kakimi

Kazunao, Kumaga Naomori and Takenaka Shigetoshi acting

as ikusa metsuke (軍目付, senior military supervisor/army

superintendent). Katō Yoshiaki, Nakagawa Hidenari, Ikoma

Kazumasa, Wakisaka Yasuharu, Yamaguchi Munenaga, Ikeda

Hideo led the Second Division and departed after them, and Mōri

Hidemoto led the Third Division and departed last. On the

water, Chosokabe Motochika and Ikeda Hideuji set sail to Yeompo

to rendezvous with Katō Kiyomasa's fleet, with Katō Kiyomasa's

troops that remained at Seosaengpo hitching a ride on their ships.

Beside the main relief force from Seosaengpo, there were other

Japanese commanders that bypassed the Seosaengpo gathering and headed to

Dosan Fortress directly. Shimazu Toyohisa that arrived at Eonyang on Day

9, as well as Kikkawa Hiroie and Mōri Takamasa, who arrived on Day 11,

were some of the more notable examples. Tōdō Takatora (藤堂高虎), who

just completed the construction of Suncheon Fortress, dispatched

his adopted son Tōdō Takayoshi and subordinate Tōdō Yoshikatsu to relief

Ulsan. Matsuura Shigenobu, who also took part in the construction

of Suncheon Fortress, personally led his troops to Ulsan. Kurushima

Hikozaemon from the currently-leaderless Kurushima Michifusa

(来島通総)'s fleet (Kurushima Michifusa was killed in Battle of

Myeongnyang), as well as Kan Uemonpachi, son of naval commander Kan

Michinaga (菅達長), also brought a portion of their respective fleets to

support Ulsan.

|

|

Bai Sai set up a second line of defence at Jeontan while Mao Guo

Qi moved to guard the river bank (click to enlarge). It should be

noted that Mao Guo Qi's movement is merely an educated guess, as

his exact whereabouts before today's order was unknown.

Nevertheless, given that Mao Guo Qi was part of Ming Left Division

and fought together with Li Ru Mei on Day 2, it's likely that he

stayed with Li Ru Mei.

|

As Japanese relief force gradually gathered at Songsan, the once-small

camp set up by the advance party now became filled with all sort of war

banners. Upon receiving scout report of this sudden increase in

activities, Yang Hao immediately realised that something was not right.

He ordered Bai Sai to lead a contingent of cavalry to reinforce Po Gui

at the northern bank of Jeontan and set up a second line of defence, as

well as sending Mao Guo Qi and his southern troops to reinforce Wu Wei

Zhong's Zhejiang infantry and guard the river bank around Dosan

Fortress.

In stark contrast to the quick reaction to Japanese activities at

Songsan, the massive increase of ships and activities at Yeompo somehow

went unnoticed by Lu Ji Zhong guarding the the river mouth only several

kilometres away from it. Perhaps this was due to carelessness, or

perhaps daily harassment of Japanese flotilla numbed his sense of

danger. In any case, Yang Hao remained oblivious to the danger and made

no arrangement to defend against Japanese reinforcement from the river,

and this grave mistake ultimately costed him the entire siege campaign.

Yang Hao was so furious over this negligence that he sacked Lu Ji Zhong

later.

Later that night, Katō Kiyomasa once again dispatched his retainer to

Songsan to plea for help.

Day 11: Day of reckoning

February 8, 1598 (26th year of Wanli reign, 1st month, 3rd

day)

February 8, 1598 was the day when the peace talk was due to take

place. Yang Hao dispatched a messenger to the outskirt of Dosan

Fortress and urged Katō Kiyomasa to come out and attend the

negotiation. The Chinese had no intention to actually negotiate with

the Japanese, however. The peace talk was but a ploy to lure out and

capture Katō Kiyomasa.

Nevertheless, Katō Kiyomasa refused to show up. Yang Hao's

messenger was greeted by Ōta Kazuyoshi from inside the fortress,

who gave an excuse that Katō Kiyomasa, along with other

high-ranking commanders inside the fortress, were gravely ill, so he

couldn't attend the negotiation personally, and no one was healthy

enough to act as his representative. And thus the peace talk fell

apart before it even started.

It should be noted that different Japanese sources give different

reasons on why Katō Kiyomasa went back on his word. Some sources claim

that a Japanese defector in the Ming army secretly leaked the ploy to

him, while other sources claim that he was stopped by Asano

Yoshinaga and his own subordinates at last minute. Regardless of the

actual reason, Katō Kiyomasa took a great gamble in doing so.

Dosan Fortress was literally on the brink of capitulation, so botching

the peace talk at this critical moment put the entire fortress at risk

of being massacred should Ming army successfully capture it later.

Fortunately for him, the gamble ultimately paid off. Help would arrive

on this very day.

|

|

Japanese fleet sailed to Ulsan, cutting off Lu Ji Zhong in the

process (click to enlarge).

|

Early in the morning at around 4 am, Japanese ships that gathered at

Yeompo—now a full-fledged war fleet, began to set sail to Dosan

Fortress. Meanwhile, Joseon naval commander Yi Un-ryong, who stayed at

Gyeonju doing absolutely nothing over the entire duration of this siege

campaign, suddenly remembered he had a untouched fleet at his disposal,

and went to reconnoitre the river. What laid before his eyes was nothing

short of terrifying, as he witnessed hundreds of Japanese ships entering

Namgang River (남강 or 藍江, lit. 'Blue River', not to be confused with

another more famous

Nam River) from the sea and began sailing upstream, thronging the entire river

with hulls and masts. Shocked by the discovery, Yi Un-ryong wrote

an emergency report to Ryu Seong-ryong (who was at Gyeongju), and

then fled as far as he could. Not only Yi Un-ryong did not engage

the Japanese to delay their advance, nor retreat to Ulsan to prepare for

a defensive engagement under more favourable conditions (i.e. with Ming

support from land), he did not even bother to send a warning to Ming

army about the incoming Japanese fleet. His selfish and cowardly action,

along with Lu Ji Zhong's negligence, wasted away precious time that Ming

army could have use to prepare for a countermeasure. As a result, at

around 4 pm Japanese fleet arrived at Ulsan in force and blockaded

entire section of Taehwa River and Dongcheon River. By that time, Ming

army was powerless to stop them (Yang Hao was so embittered by the

incident that he later urged the Koreans to build more warships).

|

|

Japanese relief force set up a new camp and began harassing Zu

Chen Xun and Wu Wei Zhong's detachment (click to enlarge).

|

Around the same time, the last of the Japanese relief

force, Kikkawa Hiroie and Mōri Takamasa, finally arrived at Ulsan.

With the relief force finally assembled, Japanese Second and Third

Division marched north and set up a new camp on a hill just south of the

southern bank of Jeontan, right before the camp of Zu Cheng Xun and Wu

Wei Zhong's detachment. Trapped between the new camp and Japanese fleet

occupying Taehwa River behind their back, both of them were cut off from

the rest of the Ming army. Worse yet, they were now being harassed by

multiple Japanese war parties, each numbering 50 to 60 troops, from the

new camp.

|

|

First Division of the Japanese relief force attempted to cross

Taehwa River only to be beaten back by Li Ru Mei and Jie Sheng

(click to enlarge).

|

Seeing that Zu Cheng Xun and Wu Wei Zhong's detachment were pinned down,

Kuroda Nagamasa, Hachisuka Iemasa, Nabeshima Naoshige of the

First Division, along with Kikkawa Hiroie and Mōri Takamasa, decided to

march straight to Dosan Fortress. With support from Japanese fleet on

the river, they attempted to forcibly cross Taehwa River at a river bank

about 2 km west of Dosan Fortress. Unfortunately, their attempt was

quickly discovered by the Ming army. Li Ru Mei and Jie Sheng led a

contingent of cavalry, along with a number of Joseon troops, and

attacked them. After a fierce battle, First Division was beaten back to

the southern side of Taehwa River.

|

|

Standoff at Taehwa River (click to enlarge).

|

At this point, Taehwa River was filled to the brim with Japanese ships,

and the entire length of the southern river bank was bristle with

Japanese troops and banners. Yang Hao realised that his was quickly

running out of options. He could either call for a full retreat before

Japanese relief force cross the river en masse, or gamble

everything and attack Dosan Fortress one last time, hoping that the

defeat of Katō Kiyomasa could seriously damage the morale of the

Japanese, allowing Ming army to deal with them somehow. Yang Hao picked

the second option, and ordered Ming army to prepare torches for the

night attack. However, before Ming army launch its final assault, Yang

Hao had to make a few adjustments to Ming deployment. He tasked Ming

Right Division with maintaining the encirclement of Dosan Fortress as

well as preparing for the attack, and drew up the rest of the Ming army

into three defensive positions.

-

Bai Sai and Po Gui remained at Jeotan, keeping a look-out against

Japanese relief force in the new camp. Joseon commanders Yi

Si-eon and Seong Yun-mun and some Joseon troops were sent to assist

them.

-

Li Ru Mei, Jie Sheng and some Joseon troops defended the river bank

between Dosan Fortress and Jeontan against potential landing of

Japanese fleet on Taehwa River, as well as potential river crossing

of Japanese troops from the other side.

-

Southern troops under Wu Wei Zhong and Mao Guo Qi were stationed

around the river confluence, guarding against both Japanese troops

at the southern bank of Taehwa River and Japanese fleet on Dongcheon

River.

|

|

Final repositioning of Ming army before it launches its last

attack (click to enlarge).

|

As for Zu Cheng Xun and Wu Wei Zhong's detachment at the southern bank

of Jeontan, they were more or less abandoned and left to their own

devices. Regrettably, since the only naval power on the coalition side

had fled, Ming army without any ships of its own would be hard-pressed

to mount a rescue operation across the river while being threatened from

at least three directions (i.e. Japanese defenders inside Dosan

Fortress, Japanese fleet on the river, as well as Japanese relief force

troops at the southern bank of Taehwa River). Ironically, as

dangerous as their position was, they were still somewhat better off

than Lu Ji Zhong, who was positioned farther away from the main army. Lu

Ji Zhong was trapped between Yeompo naval base, Japanese relief force at

Ulsan, not to mention Japanese fleet on Dongcheon River could cut off

his line of retreat at any moment. In fact, Ming army lost all contact

with Lu Ji Zhong after Japanese fleet blockaded the rivers, and no one

knew what happened to him for the remainder of the siege campaign.

While Ming army was busy preparing, Mōri Hidemoto dispatched two of

his retainers to sneak into Dosan Fortress (the fact that Katō

Kiyomasa and Mōri Hidemoto were able to sneak messengers in and

out of Dosan Fortress so easily shows the rapid weakening of Ming

troops due to lack of supply. Katō Kiyomasa had to ask for Chinese

permission to let in the "Buddhist monk" just a few days prior, but

now the encirclement had become extremely porous). The messengers

updated Katō Kiyomasa with the current status of the relief force

and its planned rescue operation in the coming days, encouraging the

defenders to hold out just a little longer.

Later that night, Shimazu Toyohisa left Eonyang and marched

towards Ulsan.

Day 12: Final Attack and Retreat

February 9, 1598 (26th year of Wanli reign, 1st month, 4th

day)

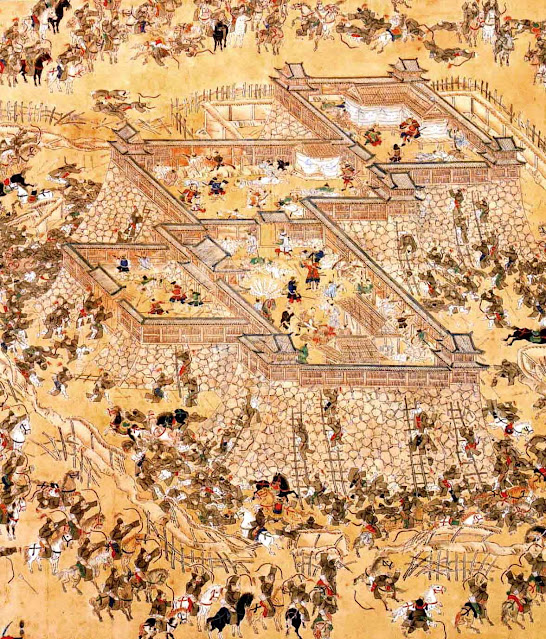

Ming army finished its preparation by midnight. Then, under the

leadership of Yang Hao, it launched one final attack on Dosan Fortress

with a ferocity second only to Day 3 assault. Ming artillerymen

relentlessly battered Dosan Fortress, setting the fortress alight, while

Ming troops set up siege ladders and attempted to climb over the wall.

Japanese defenders inside Dosan Fortress poured hails of arquebus and

ō-deppō rounds into Ming ranks, and cut down anyone that managed to

climb up. Unfortunately, days of starvation, camping in the wild under

heavy rain and freezing wind, and the death of hundreds of warhorses had

taken a heavy toll on the morale and combat readiness of Ming troops. In

stark contrast, Japanese troops were able to put everything on the line

and fought with crazed determination, knowing full well that help was

within reach. As a result, Ming army suffered heavy casualties without

making significant progress, and began to show signs of faltering and

fear. Realising the hesitation of his men, Yang Hao executed

several retreating troops for cowardice, and ordered the faltering

cavalry commander Li Hua Long to be tied up and paraded in front of the

army to maintain discipline. Ming army resumed attack with increased

ferocity. Many Ming captains led their men from the front during the

attack, often losing their lives or being seriously wounded in the

process. Among the fallen was Yang Wang Jin, a brigade commander from

Datong leading 1,000 cavalry, and the highest ranking Ming officer to

perish in the siege campaign.

|

|

A flotilla of 90 Japanese ships on Taehwa River began to slowly

sail upstream (click to enlarge).

|

While the battle raged on, a letter claiming that as many as sixteen

Japanese commanders from Gadeok Island, Angolpo, Jugdo, Busan,

and Yangsan had arrived at Ulsan with 60,000 troops was intercepted

by Ming Right Division, which reported it to Yang Hao and Ma Gui. At the

same time, Yang Hao also received report that a flotilla of about 90

Japanese ships split from the main fleet and was sailing upstream of

Taehwa River (i.e. sailing pass Jeontan), and could easily make

uncontested landing beyond the reach of Bai Sai and Po Gui and then

attack the rear of the Ming army from the west. Realising that Ming army

was under serious risk of being surrounded, Yang Hao had a brief

discussion with Ma Gui, and finally decided to call off the attack and

make a full retreat.

Shocked upon hearing the news about the retreat, Yi Deok-hyeong and a

number of Joseon officials rushed to Ming siege camp and passionately

tried to persuade Yang Hao against the idea. The Koreans even suggested

that Ming army should send a 10,000-strong detachment to occupy the

(what they considered) advantageous ground around Jeontan and the road

to Eonyang, and engage the Japanese in open battle. However, the foolish

suggestion failed to take into consideration that Japanese had total

naval supremacy, and could make landing at any point of the entire

length of Taehwa River and even Dongcheon River, so defending only the

west side of Dosan Fortress was completely pointless. Yi

Deok-hyeong also conveniently left out the fact that Joseon troops, who

were so unreliable that nearly one-half of the army deserted at the time

Ming army still had the upper hand, were now fleeing en masse in light of the worsening situation.

Unsurprisingly, Yang Hao and Ma Gui knew the unreliability of their ally

very well after fighting side-by-side with the Koreans for so long.

Given that Joseon army had abandoned the Ming army, they obviously had

no intention of being treated like cannon fodder by the Koreans. At

around 7 am in the morning, the order to cease attack and prepare for

retreat was formally issued. By 9 am, the order to retreat was also

issued, and Ming army began a full retreat. Ming infantry, as well as

wounded troops, were the first to leave the battlefield, crossing

Dongcheon River and heading east towards Gyeongju, whereas Ming

troops surrounding Dosan Fortress lifted the siege and retreated

northwards into the mountains. Cavalry commanders such as Bai Sai and Po

Gui at Jeontan, as well as Li Ru Mei and Jie Sheng at the river bank

west of Dosan Fortress, were ordered to act as rearguard and cover the

retreat for the rest of the army. Yang Hao also ordered Yang Deng Shan

to lead a contingent of cavalry to support Bai Sai and Po Gui at

Jeontan. By 3 pm, the majority of Ming army (with the exception of

rearguard and Yang Hao himself) had left, so Yang Hao ordered the

dismantling of the main siege camp on Hakseongsan and prepare for the

retreat of his own troops.

Ironically, the supply that Yang Hao had been repeatedly asking for was

finally delivered to the frontline earlier today, although at this point

the supply was nothing but extra burden for the retreating Ming troops

to carry back to where it came from. Since Ming army was unable to carry

all the supplies during the retreat, Yang Hao had to order the leftover

to be burned down to prevent them from falling into Japanese hands.

Despite this, Yang Hao still could not put his mind at ease. While

waiting for the rearguard cavalry to catch up with his troops, he

personally went to the stockpile area of the supply (at the foothill of

Hakseongsan) to make sure that everything was properly burnt down. Yang

Hao also ordered his own servants to seek out stragglers and cavalrymen

that lost their mounts, as well as scouring the battlefield to collect

discarded armours, weapons, and other materials to be burned. The

destruction of Ming war material was so complete, that the Japanese did

not even find trash inside the dismantled siege camp when they visited

the site days after, although this also caused further delays to Yang

Hao's own retreat. After making sure that nothing of value was left

behind, Yang Hao himself finally retreated at some time after 3 pm.

|

|

Ming army lifted the siege and began to retreat. Ming cavalry were

recalled to perform rearguard action (click to enlarge).

|

As for the Japanese, the defenders of Dosan Fortress quickly noticed

that Ming troops were retreating, and immediately dispatched messengers

to notify the Japanese relief force across Taehwa River. However, after

witnessing the discipline and prowess of Ming rearguard, Japanese relief

force deemed them too dangerous to attack, and thus chose a wait-an-see

approach, wasting away nearly half a day doing nothing. It wasn't until

they saw the smoke from the burning of war material, the evacuation of

the main siege camp on Hakseongsan, and even the rearguard at Jeontan

had begun to leave, that they finally decided to commence the rescue

operation. Even so, Kuroda Nagamasa and Hachisuka Iemasa of

the First Division were fearful of Ming army and hesitant to move,

further delaying the operation (unbeknownst to both of them, this act of

cowardice was witnessed and recorded by ikusa metsuke of the

First Division, and they would be severely punished by Hideyoshi because

of it).

|

|

Ming troops stranded at the southern bank of Taehwa River attacked

into Japanese camp (click to enlarge).

|

While the First Division was hesitating, Second and Third Division of

Japanese relief force inside the new camp suddenly came under attack

from Zu Cheng Xun and Wu Wei Zhong's detachment. Despite being stranded

and abandoned (Yang Hao did not even bother to inform them about the

retreat, and they were not aware that the rest of the Ming army had

left), they nevertheless stood their ground and even launched an attack

uphill. In spite of literally every odds against them, Ming

troops still fought the Second and Third Division troops led

by Mōri Hidemoto to a standstill. As such, the Second and

Third Division of the Japanese relief force were pinned down and unable

to cross the river.

|

|

Japanese First Division crossed Taehwa River (click to enlarge).

|

Meanwhile, Kikkawa Hiroie, who was positioned behind Kuroda

Nagamasa and Hachisuka Iemasa, finally had enough of their cowardice and

decided to cross the river on his own. He was reprimanded

by Ankokuji Ekei for stepping out of line and disobeying order, but

rebuked him by saying that a monk should not interfere with the matters

of a samurai (Ankokuji Ekei was a Buddhist monk) and crossed the river

anyway. Katō Kiyomasa witnessed the river crossing from Dosan

Fortress, and was so impressed by his bravery that he

thought Kikkawa Hiroie's original three flap uma-jirushi

banner was unbefitting of a samurai of such calibre. As a sign of

gratitude for being the first to save Dosan Fortress from

danger, Katō Kiyomasa gifted his own personal banner, a

silver-coloured nine flap uma-jirushi, to Kikkawa

Hiroie after the battle was over, of which Kikkawa Hiroie later added

another four flaps to the banner and changed its colour to red. On the

other hand, due to the little episode between the two, Ankokuji

Ekei would later deliberately withhold information of Kikkawa Hiroie's

bravery and exploits in his report to Hideyoshi and Mōri

Terumoto (毛利輝元).

|

|

Replica of Kikkawa Hiroie's thirteen flap uma-jirushi

displayed at the entrance of Sengoku no Niwa Museum of History

(戦国の庭歴史館), Hiroshima, Japan.

|

With Kikkawa Hiroie taking the lead, the rest of the First Division

finally got their act together and crossed Taehwa River to attack Ming

rearguard. At the same time, Japanese fleet on Dongcheon River began to

made landing, whereas Japanese troops inside Dosan Fortress also opened

its gates and poured out to support the First Division. As most of the

Ming army had left, Ming rearguard realised that they could not resist

the landing of Japanese relief force while being threatened from three

sides, so they only briefly clashed with the Japanese before retreating

(Kikkawa Hiroie, who was the first to cross the river and engaged in

combat, only managed to kill six Ming troops). After repelling Ming

rearguard, Japanese First Division established a beachhead at the

northern bank of Taehwa River. Kikkawa Hiroie, being bold as ever,

raced ahead of the rest of the First Division and

recaptured Byeongyeongseong. His decisive action successfully cut

off Yang Hao's line of retreat to Gyeongju.

|

|

Kikkawa Hiroie recaptured Byeongyeongseong, forcing Yang Hao to

change direction. Ming rearguard engaged and repelled Japanese

pursuers from Dongcheon River (click to enlarge).

|

With his eastern line of retreat cut off, Yang Hao was forced to retreat

westwards to Eonyang. Seeing that Ming army was retreating, funateshū

(船手眾, naval troops) of Japanese fleet and Katō Kiyomasa's Seosaengpo

troops that were hitching a ride on their ships seized the opportunity

and disembarked at Dongcheon River with 200 to 300 arquebuses to

chase after Ming army. Unfortunately, they ran into Ming rearguard a

mere 300 m from the river bank. Bai Sai and Yang Deng Shan immediately

launched a cavalry countercharge, shooting dead several Japanese troops,

beheading eight more, and drove the rest back to their ships. In

addition, the First Division of the Japanese relief force was still in

the process of crossing Taehwa River and had not yet amassed enough

troops to begin the pursuit operation, whereas Second and Third Division

were pinned down in their camp thanks to the action of Zu Cheng Xun

and Wu Wei Zhong's detachment. As such, Yang Hao was able to retreat in

relative safety.

With the last of the Ming army retreating, Dosan Fortress was finally

spared from its doom. Japanese ships on the river began delivering food

and supply into the fortress, and many starving troops immediately

gorged themselves full the moment they saw food. Unfortunately, this

resulted in even more death due to

refeeding syndrome.

|

|

Shimazu Toyohisa blocked Yang Hao's line of retreat, forcing him

to turn north (click to enlarge).

|

Meanwhile, Shimazu Toyohisa, who came to Ulsan from Eonyang, joined

force with the Japanese troops that disembarked from the 90-ship

flotilla and blockaded the road, cutting off Yang Hao's line of retreat

once again and forcing him to turn north and take the long

mountain route to Gyeongju. While Ming army was switching route, Shimazu

Toyohisa personally rode ahead of his army and attacked alone, beheading

two Ming troops but was lightly injured in his left ear. However,

Shimazu Toyohisa's troops consisted of foot soldiers that could not keep

up with him, so he was unable to prevent Ming army from leaving.

|

|

Wu Wei Zhong's detachment forcibly crossed Taehwa River under

heavy fire (click to enlarge).

|

|

|

Zu Cheng Xun stormed through Japanese camp and sneaked to

Seosaengpo Fortress (click to enlarge).

|

At the southern bank of Jeontan, the fierce battle in the new camp had

finally begun to shift in Japanese favour. It was an unwinnable

battle from the start, as Ming troops were starving, exhausted, and

outnumbered, not to mention they were attacking uphill against a

well-defended Japanese position held by fresh troops. As the situation

became untenable, Wu Wei Zhong's detachment decided to call off the

attack and retreat northwards, forcibly crossing Taehwa River under

heavy fire from Japanese ships on the river and pursuing Japanese troops

from the camp. As a result, Wu Wei Zhong's detachment suffered heavy

casualties, losing as many as 200 troops in battle and during retreat.

On the other hand, Zu Cheng Xun had a different idea. Instead of

retreating to the north, he gathered his retinue cavalry and

charged through the camp. In the ensuing fierce battle, Zu Cheng Xun's

own horse was shot out from under him, and many of his retinue cavalry

also lost their mounts. Nevertheless, they still managed to break out of

Japanese encirclement and escaped south. Still unsatisfied with the

outcome, Zu Cheng Xun and his troops sneaked to Seosaengpo Fortress

(now largely empty since most Japanese troops had left for Ulsan) later

that night and stole the signboard on its bridge before slipping back to

friendly territory.

|

|

Japanese Second and Third Division crossed Taehwa River,

captured Hakseongsan, and rendezvoused with First Division

(click to enlarge).

|

After the attack on Japanese camp was dealt with, Second and Third

Division of the Japanese relief force were finally able to cross Taehwa

River. They occupied a high ground near the northern bank of Jeontan,

but did not immediately chase after Ming army. Instead, Mōri Hidemoto

assigned his troops to guard the high ground, while Second Division

moved towards Dosan Fortress to capture the (now vacant)

Hakseongsan and rendezvous with First Division. In the mean time, First

Division also completed its river crossing.

|

|

Final encounter behind the hill of Baegamsa Temple (click to

enlarge).

|

With Dosan Fortress completely secured and large numbers of troops

congregating together, Kuroda Nagamasa finally gathered enough

courage to begin the mopping up and pursuit operation in the earnest.

Japanese relief force successfully killed a number of stragglers, and

was able to quickly close the distance with the retreating Ming army,

finally catching up with Yang Hao's troops behind the hill of Baegamsa

Temple (백암사 or 白奄寺, present day

Baeg-yangsa Temple), about 4.8 km away from Ulsan fortress complex. To shake off the

pursuers, Yang Hao once again ordered Ming rearguard cavalry to cover

the retreat. Li Ru Mei and Jie Sheng launched a cavalry charge against

the Japanese, killing a number of Japanese troops and drove the rest

away. However, after Ming rearguard cavalry returned to their formation,

Japanese relief force resumed its pursuit and began trailing the Ming

army from a safe distance for another 3 km. The tense stare-off was

finally broken when two mounted samurai carrying white banners rode

closer to the Ming army to probe its response. Both of them were

promptly beheaded by Ma Yun (麻雲) and Wang Guo (王果), Ma Gui's retinue

cavalry. Seeing that Ming army closely guarded its retreat,

Japanese relief force finally gave up and returned to Ulsan.

And that left us with Lu Ji Zhong. Due to the fact that he lost all

contact with the rest of the Ming army and no one knew what happened to

him, most Korean sources presume that his entire unit of 2,100 troops

was wiped up to the last man. However, it can be known from other

sources that Lu Ji Zhong was later sacked by Yang Hao, and the command

of his troops was transferred to his successor, Chen Chan (陳蠶), who

later had a merger with another 1,600 troops to make a 3,000-strong

combined regiment. In other words, despite suffering the heaviest

casualties among all Ming units, Lu Ji Zhong still managed to escape

with large portion (1,400 troops out of 2,100 total) of his unit intact.

Aftermath

Having rid of the pursuers at last, Yang Hao returned to Gyeongju

safely, although he only made a brief stop at Gyeongju before heading

to Andong. Meanwhile, Japanese relief force also returned from the

pursuit and encamped at Ulsan Eupseong (Ulsan walled town). Later that

night, commanders of the relief force went to Dosan Fortress to meet

the commanders of Dosan Fortress. Katō Kiyomasa, Asano Yoshinaga,

and Ōta Kazuyoshi then wrote a joint final report back to Japan,

detailing the entire siege and relief of Ulsan.

A day after the siege (February 11, 1598), Ryu Seong-ryong saw that

there were still many surplus supply meant for Ming army left in

Gyeongju, so he ordered Seong An-ui (성안의 or 成安義) to

distribute the supply among Joseon troops, under the pretense of

preventing the supply from falling into Japanese hands (he later

proclaimed that the Koreans did their utmost to keep the frontline

well-supplied, notwithstanding the fact that Ming troops starved at the

frontline while supplies continued to pile up in Gyeongju). In addition,

Ryu Seong-ryong and Gwon Yul managed to rally about 800 Joseon

stragglers returning from Ulsan and stationed them in Gyeongju to defend

against potential Japanese attack, but allowed the rest to return home.

On the Chinese side, despite the failure of the siege campaign, Ming

army still took up the defence of Korea. At the beginning of March, some

Ming commanders that returned from Ulsan (as well as additional

commanders that entered Korea after the siege) were reassigned to defend

various places in Korea: Li Fang Chun, Lu Ji Zhong, Li Hua Long, Lu De

Gong and Niu Bo Ying (牛伯英) were assigned to defend Andong; Ye Bang

Ron (葉邦榮) to Yonggung; Wu Wei Zhong to Chungju; Chen Yu Wen to

Suwon; Lan Fang Wei (藍芳威) to Jiksan; Li Ning (李寧) to Gongju;

Dong Zheng Yi, Chai Deng Ke (柴登科) and Qin De Gui (秦德貴) to Jeonju;

as well as Bai Sai to Anseong. The rest of the Ming army gradually

returned to Hanseong, as were Ma Gui and Yang Hao, who returned to

Hanseong on March 14 and March 22 respectively.

Analysis

From the onset, this blog post dispelled several prevailing myths about

Siege of Ulsan, as well as Imjin War in general, including but not

limited to:

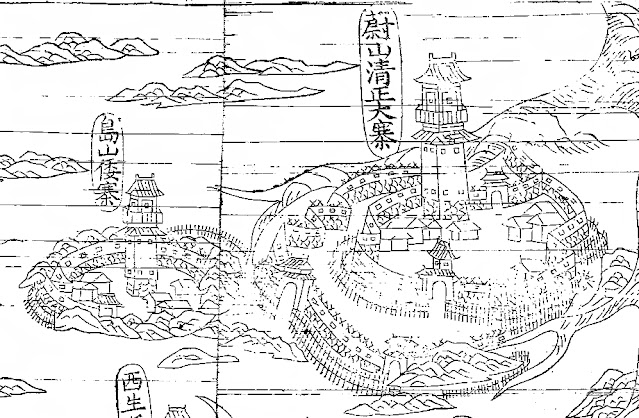

-

"Ulsan Japanese Castle" was a single castle (it was actually a

massive multi-fortress complex, as were all other Waeseong in

Korea);

-

Ming army suffered heavy casualties due to undisciplined retreat,

leaving its troops vulnerable to Japanese pursuit (Ming army

actually retreated in good order and protected its rear remarkably

well, and only suffered relatively light casualties);

-

The disorganised retreat was caused by Yang Hao fleeing before his

army, causing the rest to break ranks (Yang Hao actually stayed

behind and was among the last to retreat);

-

Japanese fortification design and mastery of matchlock firearms

conferred them unique advantages against contemporary Chinese siege

tactics (on the contrary, Ming army quickly captured all but one

fortresses of the entire complex, and nearly captured the last

one).

That said, the strategic implication of Siege of Ulsan actually goes

well beyond debunking a few myths. However, in order to fully grasp the

impact and importance of this battle, one must look at the big picture

of the second invasion, both before and after the siege campaign.

As mentioned in the prelude, after the breaking down of peace talk in

1597, Toyotomi Hideyoshi launched the second invasion with

never-before-seen ferocity. Neither Joseon military nor righteous army

was able to put up any meaningful resistance against the Japanese

onslaught, and Joseon navy, the crown jewel of Joseon military might,

was virtually obliterated during Battle of Chilcheollyang. Even Jeolla

Province that survived the first invasion fell into Japanese hands.

Essentially, the war unfolded much like the first invasion, only this

time Joseon Kingdom was already devastated, its military in shambles,

and its naval dominance completely undermined.

To put things into perspective, in 1592 (before the first invasion),

Joseon army had 180,000 troops stationed around the vicinity of Hanseong

alone, and could muster as many as 400,000 conscripts using

Hosu-Boin system (호수보인 or 戶首保人, a system where one

soldier, known as Hosu, was supported by tax revenue from several common

folks, known as Boin) should the need arise. Even after Joseon army

suffered heavy losses during the first invasion, a census conducted in

early 1593 shows that the combined strength of Joseon army, Joseon navy,

and various

righteous army

groups of entire Korea still numbered 172,400, with Jeolla Proving

having 10,000 army troops and 15,000 naval troops, and Gyeongsang

Province having 35,000 troops stationed at Ulsan and Andong. However, by

mid-1597 (before the second invasion), Joseon military had deteriorated

to the point that there were only 1,500 troops left in Jeolla Left

Province, as well as 11,100 army troops and 5,000 naval troops in

Gyeongsang Province.

As if such terrible state wasn't bad enough, Japanese army once again

wreaked havoc across Korea during the second invasion, further degrading

the strength of Joseon military. By the time Ming army was preparing to

attack Ulsan, Gyeongsang Province could barely scrape together 3,000

troops to support the effort. Moreover, Jeolla Province fared even worse

than Gyeongsang Province. At the beginning of February 1598, Yi Kwang-ag

(이광악 or 李光岳), Army Commander of Jeolla Province, only had 500

troops under his command, most of them rabbles. Other Jeolla commanders

fared even worse, even better-off commanders barely had 70~200 men under

arms, and many could not muster even a single troop. Even the

once-numerous righteous army of Jeolla Province had been shattered into

fractured warbands numbering only 20~70 men per band.

The crisis was so dire that Hanseong once again came under grave

danger of being captured by the Japanese. Residents of Hanseong fled the

city en masse, almost hollowed out the capital, and even

Joseon King Yi Yeon was contemplating to send his princes and harem away

to safety. Although Hanseong was ultimately spared from this terrible

fate because Japanese invaders decided to halt the attack and

consolidate, the Koreans understood that the crisis was far from

averted: The Japanese held all the cards and could resume aggression at

any moment; both Joseon army and navy were ravaged and toothless, and

the prospect of evicting the invaders from Korean lands was looking

increasingly bleak.

As such, Ming intervention was the last, and in fact only, hope for

Korea. The fact that Ming Dynasty sent in reinforcement alone was

already greatly inspiring, and the news of Katō Kiyomasa's defeat

at the hands of Ming army during the early phase of Siege of Ulsan was

cause for celebration. Even after the failure of the siege campaign,

contemporary Koreans mostly expressed disappointment and regret that

Ming army wasn't able to finish off Katō Kiyomasa once and for all,

rather than seeing it as a debacle/complete failure.

As much as Siege of Ulsan motivated the Koreans, its impact on the

Japanese was even more profound. On October 19, 1597, two days after

Battle of Jiksan, Japanese commanders held a war council

at Jincheon. During the council, Ōta Kazuyoshi (one of the ikusa metsuke

of Japanese army) instructed the Japanese commanders to return to the

southern coasts of Korea in order to recuperate and wait for the winter

to pass. He also announced that the offensive should resume in the

coming spring (April 1598), where a well-rested Japanese army would

march straight to Hanseong. However, the Japanese did not expect a Ming

counteroffensive to come so early, before they were able to fully settle

down, much less preparing for the 1598 spring offensive. Although Ulsan

Fortress ultimately prevailed against Ming attack, it suffered severe

damage in the process, losing most of its facilities, stored food, war

materials, garrison troops, and more importantly, its function as a

forward base to support the offensive. Furthermore, the threat of

another Ming attack still loomed over the heads of Japanese commanders.

Fearing for the safety of their own fortresses, many Japanese commanders

in Korea petitioned Hideyoshi to abandon Ulsan and Suncheon Fortress in

order to narrow down the battlefront to a more manageable size, of

which Hideyoshi angrily declined. Not one to give up easily,

Japanese commanders petitioned Hideyoshi for the second time, this time

adding Yangsan Fortress into the list of fortresses to be

abandoned. Hideyoshi was understandably furious and harshly

criticised the cowardice of Japanese commanders, but even he realised

that the situation was untenable and eventually ordered the abandonment

of Yangsan Fortress and Gupo, and later pulled out one-half of Japanese

invasion force from Korea.

By this point, no one on the Japanese side was thinking about the 1598

spring offensive anymore. In fact, it was not until April 4, 1598 that

Hideyoshi brought up the resumption of the offensive again. In a

letter addressed to Tachibana Muneshige (立花宗茂), Hideyoshi

mentioned that he wanted to sent another army to Korea in 1599 to resume

the offensive, and ordered Japanese commanders in Korea to procure food,

gunpowder, and other war materials to support the operation. Another

letter written by Fukuhara Nagataka (福原長堯) et al.

to Shimazu Yoshihiro in June 29, 1598 reaffirmed the plan, and

named Fukushima Masanori (福島正則), Mashita Nagamori (増田長盛), and

Ishida Mitsunari (石田三成) as the commanders that would lead the 1599

offensive. Additionally, Ulsan was selected as the landing point for the

new invasion force.

Essentially, Japanese army's entire strategic plan for the second

invasion was derailed. Not only the planned 1598 spring offensive was

completely ruined, forcing Hideyoshi to delay the invasion for another

year, Japanese army was forced into defensive by an enemy one-third its

size (only 40,000 Ming troops had entered Korea at this point, while

Japanese troops in Korea numbered about 140,000), losing all the

initiative and momentum it built since the beginning of the second

invasion.

In July 1598, due to deteriorating health, Hideyoshi ordered Katō

Kiyomasa to restart the peace talk, only this time he dropped everything

in his list of demands (including the cession of Korean provinces,

sending a Joseon prince to Japan as hostage, yearly tribute, and

submission of Joseon Kingdom to Japan) and only asked for one thing: an

apology from the Koreans. Whether that apology was made by Joseon King

or some unnamed nobody mattered not to Hideyoshi, as long as he received

one, he would end the war. After spending seven years waging a fruitless

war, throwing away tens of thousands of lives as well as untold amount

of wealth in the process, Hideyoshi was now eager to end it. The demand

for apology was no more than a face-saving gesture to satisfy his ego,

as well as a last-ditch attempt to hold onto some kind of moral high

ground.

Thus it's fair to say that Siege of Ulsan was the single most important

battle of the second invasion, as well as its real turning point. Even

though Ming army retreated without accomplishing its objective, the

actions of Japanese commanders in Korea as well as Hideyoshi himself

after the siege campaign clearly show that they were rapidly losing

control of the situation. Moreover, all this while Ming army was able to

build up its strength in Korea unhindered, and by September 1598 as many

as 74,400 Ming troops and 24,000 horses had gathered in Korea. From then

on, Ming-Joseon coalition went from being constantly on the defensive

during the early phase of the second invasion to having secured defence

and capable of going on the offensive. In contrast, Japanese army was

forced from a dominant position in full control of the war into a

vulnerable position constantly preoccupied with reacting and responding

to the changing situation. All of these were directly or indirectly

caused by Siege of Ulsan.

Missed opportunity

It should be noted that neither the Chinese nor the Koreans were fully

aware of the instability and chaos on the Japanese side. Due to the

massive debacle that was the previous peace talk, which resulted in the

execution of chief negotiator Shen Wei Jing (沈惟敬), no one in the Ming

army dared to even entertain the idea of re-enter negotiation with the

Japanese anymore. As a result, Ming army continued to amass troops and

gather supply in Korea while purposely ignoring repeated attempts

from Katō Kiyomasa and Konishi Yukinaga to make peace.

Unfortunately, just when Ming army completed the mustering of troops and

Yang Hao was about to put his plan of a new offensive into motion, a

memorial to the throne

written by Ding Ying Tai (丁應泰) in July 1598 sparked a massive

internal feud in both the Ming court and the Ming army in Korea, to the

point that even Joseon court was dragged into the chaos. Ming army was

paralysed by the scandal, wasting away three whole months (July to

October) doing literally nothing. By the time the dust began to settle,

Yang Hao was already discharged in disgrace, Ding Ying Tai ascended to

power and began to lord over the rest of the Ming military leadership in

Korea, and Ming army was heavily disheartened and beset with confusions

and internal strives. As a result, it severely underperformed in the

three sieges that followed. For example, there was little to no

coordination between Ming army led by Liu Ting (劉鋌) and Ming navy led

by Chen Lin (陳璘) during

Siege of Suncheon (Liu Ting barely had any motivation to fight), whereas a

gunpowder accident during

Siege of Sacheon resulted in the most humiliating Ming defeat of Imjin War. The most

egregious one, however, was none other than

Second Siege of Ulsan. The second siege failed not because of any mistake on Ming army's

part, but because Ding Ying Tai forcibly ordered Ma Gui to cancel the

siege and return to Gyeongju "for inspection". In stark contrast, thanks

to the internal strife that paralysed Ming army, Japanese army managed

to weather through its worst period of instability and weakness, and

began to slowly regain footing. By the time a demoralised Ming army

relaunched its offensive in October 1598, Japanese army had sufficiently

stabilised and fought off the three sieges with remarkable competency.

In fact, the whole offensive could've ended up as a massive blunder if

not for

Battle of Noryang, of which the Ming-led coalition navy inflicted the single heaviest

casualties to Japanese navy since the beginning of Imjin War, thus

preserving the reputation of Ming military somewhat.

To summarise, Siege of Ulsan decisively tipped the balance of war in

favour of Ming-Joseon coalition, forever preventing the Japanese from

ever achieving their objectives. However, both Ming court and Ming army

were soon caught up in a massive internal feud, not only wasting away a

golden opportunity to take advantage of the favourable situation, but

also dragging out the war unnecessarily. Regrettably, despite committing

an ever-increasing number of troops and resources into the war, in the

end Ming army still fell short of achieving a complete victory.

Attributions and Special Thanks

While originally I planned to write this blog post based on my original

research, I quickly came to realise that neither my knowledge on this

topic, nor access to historical documents, nor my ability to understand

and interpret those documents to construct a comprehensive narrative are

up to the task. As such, the completion of this article would not be

possible without massive amount of inputs and guidance from

Mi Zhou Zhai

(米粥斋), an expert in the field, through an intermediate (who wishes

to remain anonymous). I also borrowed heavily from

《万历朝鲜战争全史》written by

Zhu Er Dan (朱尔旦), who also penned the

three-part

critique of Samuel Hawley's book

that I translated. For that, I owe them my utmost gratitude.

Great write up so far. Looking at the modern pic of Dosan Fortress on the raised hill it looks like a great place to build a fortification, being on high ground and overlooking the surrounding area. You mention the Chinese and Koreans rarely build 'castles' in the Japanese (and medieval European) style, ... I wonder why? Probably because of the 'feudal' nature of the Japanese and Middle Ages Europeans with their plethora of daimyo and barons constantly fighting each other in worthless feuds, while China and Korea were more state level actors perhaps ??

ReplyDeleteChinese and Koreans did build similar-sized fortresses, but those are generally of the "wall with buildings inside" kind (essentially a "shrunk down" walled city), without an obvious keep/tenshukaku. Chinese called these smaller fortresses Zhai (寨), Bao (堡) etc, and that's what they called Japanese castle too.

DeleteSuch a nice work im waiting for its continuation!

ReplyDeleteI want to ask a guestion, Im from Turkey and i really love Chinese-Korean-Japanese history. I want this passion to spread therefore im going to make a roleplay game of Imjin War with even Jianzhou Jurchens playable. I want units to be accurate and not as simple as "pikemen swordsmen archer cavalry". I want to add some egzotic units and weapons such as fire lances and rocket wagons. But i really lack the information, can you tell me some Late Ming Chinese units and weapons to me so i can make Ming Chinese army enjoyable?

Thank you!

Good day and welcome to my blog.

DeleteImjin War is a highly complex topic given the multiple sides (and sources) involved, so it's difficult to accurately reconstruct the exact equipment of the armies involved.

Jianzhou Jurchens did not participate in the war. Only Kato Kiyomasa briefly intruded into their territories and fought with them (it went badly form him).

Did Kato Kiyomasa's skirmish with the Jurchen go badly for the Japanese? I've read that his muskets made mince meat of Jurchen cavalry. Do we have any more details about this amazing encounter? What did the Japanese make of the Jurchen? did they even know who they were? what did they make of their tactics, what did the Jurchen think of the Japanese? It's been said Nurhaci offered to aid the Ming and Koreans in the Imjin War, but the Ming declined. Interesting if the Jurchen did intervene against the Japanese, how would they have faired against the might of the entire Japanese invasion force?

DeleteI will make every nation playable therefore everyone will have the freedom to declare war on whatever country they want thats what i meant :D

Delete@Der

DeleteThose are generally heavily exaggerated later period sources intended to glorify and justify Japanese invasion of China.

Basically, Kato Kiyomasa crossed Tumen River into Yanbian and attacked/destroyed several Jurchen settlements, which provoked the Jurchens to attack him. According to Korean source, his force suffered heavy casualties and returned to Korea.

According to "Kiyomasa Korai-jin Oboegaki", a primary source written by Shimokawa Heitayuu (Kato Kiyomasa's subordinate and participant of the battle), some 8,500 Japanese troops fought valiantly against "tens of millions" of Jurchens, they were surrounded, but saved by a timely "divine downpour" (rain version of Kamikaze basically) and retreated to Korea the next day.

The Jurchens then lay siege to Kilju (then under Kato Kiyomasa's control, but he was not present there). Kato requested Nabeshima Naoshige's aid to lift the siege.

The Japanese were aware of the Jurchens and described their settlements as "foreign" but noting much beyond that. They called the Jurchens they fought "Orankai (兀良哈)" which seems to be used loosely/derogatorily to refer to generic "barbarian".

DeleteIn Chinese context, that name usually refers to a specific Mongol subgroup (Uriangqais), which the Japanese certainly did not encounter. I am not entirely certain which Jurchen tribe was encountered by Kato Kiyomasa, as I am not familiar with early Jurchen/Manchu history, although I've read discussion that suggest that it was Warka Jurchens.

@Ali Emre Azgın

DeleteYes, I understand the draw of "what-if" scenario and exotic gadgets of war, although they are by definition not historically accurate.

I can only give you a broad and crude overview:

The majority of Ming troops that went to Korea were Northern Chinese border troops, most of them can be classified as multipurpose medium cavalry (armoured rider on unarmoured horse, armed primarily with bow and arrows + sabre, many also wielded some kind of polearm or matchlock/handgonne). Rocket was used fairly extensively by Ming cavalry.

Ming infantry were much more varied and generally came from Southern China and included everything in the usual roster (pikemen, swordsmen, archers, matchlockmen, artillerymen, also cavalry). Many of them were "double-armed" (usually one melee and one ranged primary weapon, i.e. pike + bow, polearm + rocket etc)

Fire lance was no longer used by Ming army except in naval battle and sometimes for siege (the so-called fire lance was actually a powerful one-use flamethrower, ranther than a weak peashooter attached to a spear). I am not aware of explicit record of Chinese use of rocket wagon during Imjin War, but given the amount of rocket they brought, they probably did.

Thank you!

Delete@ Ali Emre Azgin

ReplyDeleteMost the Ming troops sent to Korea during the Imjin War were northern border cavalry, and they wouldn't be that much different from the more iconic Mongol and Manchu cavalry of the same era. Their main weapons were bow and arrows, saber, and lance or polearm. Their armor would be brigandine, basically a long cotton coat riveted with squarish metal plates on the inside. The northern troops carried some firearms too, but mostly cannons, rockets, and outdated handgonnes like the iconic three-eyed gun, with few to no matchlocks. And presumably they would have used some war wagons too, both for offensive (especially as a platform for launching rockets) and defensive purposes, as well as for transporting equipment and supplies.